On a recent morning, I walked into my living room at 9 a.m. as I always do, ready to start the day, only to find that my three children had already started “school” without me. My oldest child, a 9-year-old boy, had dragged a small chalkboard easel up from the basement and was demonstrating simple addition and multiplication problems to his 6-year-old brother and 4-year-old sister, who sat on little chairs behind a child-sized table. I sat down on the couch, dumbfounded.

Although I have homeschooled my children for the past three years, this scene bears little resemblance to how I teach. My method, insofar as there is one, is more open-ended—learning as a natural part of life, not the study of clearly delineated subjects. Aside from the birdsong streaming in from our open front door and a cat walking on dirty paws across the table where my younger children sat, this scene looked a lot like a traditional classroom.

For whatever reason, my son had taken on the mantle of teaching. He was playing at it, as children do, but he was also doing a good job: carefully crafting his questions for each of his siblings based on his understanding of their differing abilities and gently guiding them to the answer if they appeared to be struggling. I watched silently from my perch on the couch for the next 90 minutes, as he launched into a phonics lesson and then proceeded to read aloud an entire book of poetry. Sensing the energy had shifted, he closed the book, pronouncing it “beautiful,” and then made lunch for everyone. Afterward, he declared it “recess for the rest of the day.”

That day was our best day, and I hold the snapshot of it in my mind’s eye on the days when the scene is one of tears and frustration. But many of our days are nearly that good, and they feel a world away from where we were when we started homeschooling, having been forced to face the fact that our bright and inquisitive eldest child was miserable in his first foray into formal schooling. Midway through his kindergarten year, the long days spent at a desk filling out reams of worksheets had sapped him of his natural curiosity, and rather than play with his siblings when he got home from school, he just picked fights with them.

The hardest part of his transformation to accept was that it was done in service to goals that my husband and I didn’t share. We didn’t care that our son be able to read by the end of kindergarten (although he could) or that he earn high standardized test scores (although he did). We cared that he be intellectually stimulated, have lots of time to play, and have the opportunity to socialize and make friends. Yet his school—the darling of an A-rated district—was meeting none of those needs.

I knew that this wasn’t the way school had to be. The year before, when we lived in Canada, he had attended a public Waldorf school. There, in his mixed-aged kindergarten of 20 4- to 6-year olds, there were no desks, no worksheets. Instead, there were toys and crafts and music and art, and most of the day was spent at play in a beautiful room glowing in warm pastels. It was more or less like the public kindergartens my husband and I had attended 30 years before.

At one point, I unburdened myself to a mentor—a veteran Waldorf kindergarten teacher turned educational consultant—and her recommendation stopped me short. “Can you homeschool him?” she asked. I told her I didn’t think I was cut out to be my son’s teacher, that it would derail my own career. But the cold truth was I didn’t like the child my son had become well enough to want to spend all day every day with him, a secret shame I have since learned I share with many parents. Nor could I imagine being responsible for his entire education, when I couldn’t even make him do his homework.

By January of his kindergarten year, I was so tired of the nightly battle over homework that I stopped asking him to do it, only to discover weeks later that his teacher had been making him miss recess in order to complete the untouched worksheets. The final straw was when we were informed that if we took a long-planned trip to France, piggybacking on my husband’s stint as a visiting academic there, my son would have to repeat kindergarten. The district had a zero-tolerance policy for too many unexcused absences.

To be clear, I do not fault my son’s teacher or his particular school for what happened. They are all gold-star exemplars of our current highly standardized educational system, and they have little discretion in what or how children are taught. My son’s teacher—with her decades of classroom experience—was required to teach from a literal script; some subjects, such as math, were delivered via video straight from a representative at Pearson educational publishing. All of it was canned content written to a common standard: Here are the 637 discrete skills every kindergartener should know, with a corresponding worksheet for each. It was utterly uninspiring. I finally convinced myself that I could do at least as well as this.

That summer, after returning from France, I reacquainted myself with the Waldorf approach, bought a first-grade curriculum to use as a guide, and dropped a postcard in the mail to our local attendance officer informing her of our intent to homeschool.

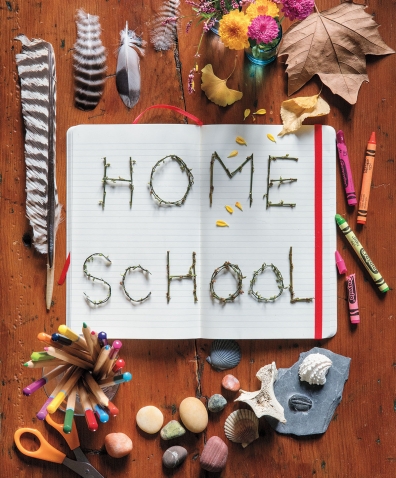

Early on in our homeschooling efforts, I tried to recreate that ideal classroom I had glimpsed back in Canada. Like my kids’ set-up in my living room that morning, we “played school” that first year, complete with chalkboard and class schedule and walls I repainted in soft muted tones. But it soon became clear to me that there would not be much advantage in upending our lives if we merely reproduced school at home.

Luckily for us, there are no requirements for homeschoolers in Mississippi, where we live. That postcard to the attendance officer is the only oversight required by law—a thought as terrifying as it is liberating. When you remove the burden of external supervision, it changes the calculus of learning. If no one is watching, what are we learning for? Our educational goals have become the ones we set for ourselves. We do a thing not because it checks some curricular box but because it is interesting and worth doing, because it has value to us.

Because music and art are valuable to us, we do a lot of both, every day. My two older children each play the piano and a string instrument. We draw and paint, knit and sculpt. In my son’s last school, these subjects were called “specials,” and his class was allowed only one of these “specials” per week. Recently, we finished weaving a runner for our dining table. Over the course of three years, we learned to dye our own wool, had a friend spin it into yarn, and bought a loom and learned how to use it—just because we thought it would be an interesting thing to do, because it would add beauty to the table that is the beating heart of our home.

Similarly, what we study has a context. Our science for this year has been mainly ornithology because my kids wanted to know the names of the birds visiting our backyard feeder. To this end, each child has been creating a personal “bird book,” and along the way we have studied the life and work of the naturalist John James Audubon, who was the first to catalog many of the species in the woods and on the waters near our home. What my kids learn at home is narrower than what they would learn in school, but, I think, deeper.

The cornerstone of our homeschool is a steady diet of wonderful literature. Each morning, we curl up on our sagging gray couch with cups of tea and a stack of books that threatens to topple off the ottoman. As I read aloud, my children busy their hands with some embroidery or drawing or play dough, and more often than not my tea has cooled before I have remembered to take a single sip, so lost am I in “doing the voices” in the story or answering my children’s endless questions. In this way, we have journeyed out of the jungle with Mowgli, across the frontier with the Ingalls family, and to Neverland and back with Peter Pan. Many of these books I, too, am encountering for the first time, so as often as not, I am the one asking to read “just one more chapter.”

An odd coincidence, perhaps meaningful: When I was in the 10th grade, I presented my parents with an urgent plea to be homeschooled and a six-page syllabus of all the things I wanted to study, including a detailed reading list. It wasn’t that I didn’t like school per se, it was that I was frustrated by my lack of free time to pursue what interested me. When I wasn’t in school or doing hours of homework each night, I was busy racking up the extracurricular activities that would make me an attractive applicant to a selective college like Wellesley. The irony was not lost on me, even at the age of 16, that I was asking to leave school to have the freedom to immerse myself in scholarly subjects. Of course my parents said no. My mom was a teacher at my own high school.

With this in mind, I have tried to give my children a great deal of liberty in choosing what we study. This year, when my boys made it clear that my plan for the year didn’t interest them all that much, we shifted gears to what did: “Mummies and mythology,” they said, and I tweaked that into a survey of classical antiquity. Big thematic topics have become the vehicle for teaching the skills I think are important. Over the past nine months, as I have taught my 6-year-old to read and write, we have studied how humans learned to read and write. We made hieroglyphic scrolls and cuneiform tablets, we explored the alphabetic and numerical systems of the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians. Much of our math this year has involved working through the discoveries of Pythagoras, Eratosthenes, and Archimedes. Reading children’s versions of The Iliad and The Odyssey, the tale of Gilgamesh and stories from the Hebrew scriptures have caused us to ponder together the age-old question “How should one live?”—which seems to me the fundamental reason for studying anything.

Freedom is built on trust, and I realize in retrospect that a big part of the reason my parents didn’t allow me to homeschool myself was out of fear. They didn’t trust that left to my own devices I would make good use of my time, or, perhaps, that I would get in to college. But if I’ve learned anything as a parent, it is that a child’s own curiosity is his best instructor. There’s an oft-misquoted chestnut, usually attributed to Yeats, that “Education is not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire.” Whoever may have said it, the sentiment has become my touchstone.

At the end of the day, I try to ask not what did we accomplish from our daily agenda, but were my kids inspired? During the first year of our homeschooling, my then-7-year-old became enamored with the first Harry Potter novel and was burning with enthusiasm for his new ability to read big, chunky books. So for an entire month, I let him use our school time to read all seven volumes. I trusted that there was nothing more important he could be doing than to learn to love reading.

Perhaps the most vital aspect of our school is not like school at all: play. “Play is the work of childhood,” Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget said (and Fred Rogers famously echoed). Like those two, I believe young children need lots of unstructured, open-ended play—not the 20 minutes of recess allowed per day to elementary students in my district, but hours and hours of the stuff. So while my children are still very young, play is our priority. At most, we “do school” three or four mornings a week. On Thursdays, and often on Fridays, too, we spend the entire day with dozens of our homeschooling friends, playing in the woods or on a small family farm, in every kind of weather. My kids call these our “Forest School” days, but there are no educational objectives to these outings, although we have learned a lot: how to identify local flora and fauna, how to spot the heralds of the changing seasons, how to catch a salamander and avoid a snakebite. I can easily imagine that of all the things we have learned together, these will be the only lessons my children will never forget.

Going back to our best day, what stands out for me the most is how proud my son was of teaching his younger siblings. His dimple deepened and his eyes shone as he asked me, afterward, in the chummy manner of one professional to another, “Don’t you think today has been our best school day ever?”

I’m not sure if I have ever loved him more than I did at that moment, and I was reminded that one day—and probably sooner than I expect—it will be time for me to take a back seat in their schooling, when my children prefer a more traditional-looking classroom than the one I have created. And that’s OK. I have faith that they will have the skills to take charge of their own educations the way my son took charge of our homeschool that day. After all, hadn’t that been the point of our experiment?

My decision to homeschool began as an acute dissatisfaction, but it has become much more than that. I have discovered that I relish the process more than the outcome—the day-to-day experience of living and learning together. Somehow, without my being able to measure it, or even really noticing, my son had been absorbing this lesson all long. Now, it was my turn to sit back, watch, and learn.

Sarah Ligon ’03 is a freelance writer and editor who homeschools her three children in Oxford, Miss. She chronicles her homeschooling adventures on Instagram @themotherofinvention.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.