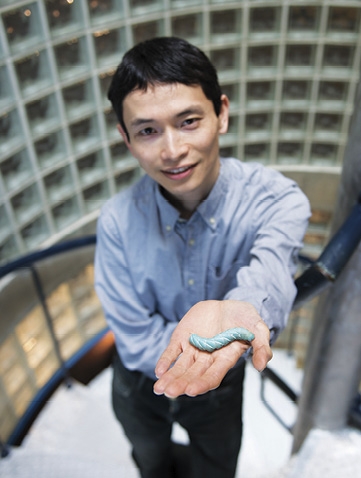

Photo by Richard Howard

If you grow tomatoes, you might not be fond of tobacco hornworms—four-inch-long, bright-green caterpillars that can make short work of your crop’s leaves overnight. But Yui Suzuki, associate professor of biological sciences, has a soft spot for the chubby critters.

Suzuki studies evolutionary development (evo-devo, for short) in insects. A goal of evo-devo is to look at the common genes shared by very different organisms—tobacco hornworms and humans, even—and attempts to answer questions about how, exactly, organisms developed their unique physical attributes. Tobacco hornworms’ physiology has been studied very thoroughly, Suzuki says, but not their genetics. “One of my goals is to bring the genetic perspective into the physiology that’s already been established,” he says. Also, “they never seem to get sick.” A good thing, since he estimates that one of his students has raised “probably close to 1,000” of them in the course of their research studying the genetic mechanisms underlying molting and metamorphosis.

Suzuki emphasizes the important role that students play. For example, while in his lab, one of his former students, CeCe Cheng ’12, serendipitously discovered a transcription factor—a protein that regulates the expression of genes—that affects the production of hormones that control metamorphosis and reproduction in the red flour beetle. “The really fascinating thing is that the same transcription factor is also found in humans and other mammals. Those genes are necessary for forming the pituitary and the hypothalamus, and they also play a role in reproduction. So we were excited, because we think that maybe there was a common ancestor of mammals and insects that used the same transcription factor to regulate hormones,” he says.

Suzuki has branched out beyond insects on some projects. A couple students in his lab are working on a new experiment on crustaceans called Parhyale, studying the expression of transcription factors related to hormonal structures. Right now, students are trying to figure out how to rear the Parhyale, which are less than an inch long. “They’re pretty cute,” he says. But they’re no tobacco hornworm.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.