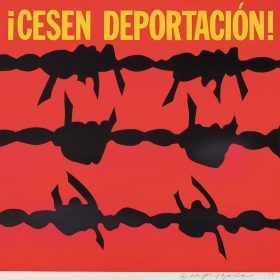

In 2005, while Beth Matusoff Merfish ’05 was doing research for her Wellesley thesis at Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum, she made a discovery that has influenced her career ever since. Guided by an academic footnote and the advice of a veteran museum employee, Beth found 10 unmarked boxes in a closet. They turned out to be a trove of 500 prints, most of which originated out of Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), an anti-fascist visual art collective that flourished in Mexico City in the 1930s and ’40s. A large portion of the prints were made by Elizabeth Catlett, a Black artist from the United States who studied at TGP and went on to create works exhibited by museums like the Whitney Museum of American Art.

For the first time in decades, a number of works from the boxes Beth discovered 15 years ago were shown to the public. In collaboration with her students at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, where she is now an associate professor of art history, Beth curated the exhibit Local and Global: TGP Prints from the Radoff Collection. It opened in late 2020 at the university, and she says it had an emotional impact on her students. One of the Mexico City prints, for example, featured people who happened to physically resemble a student’s grandparents. “She [told me] it was the first time she had ever seen an image reminding her of [these relatives] within the walls of the university,” says Beth.

Beth’s career has focused on amplifying marginalized voices in art. For over a decade, she has studied the work of printmakers who lived in Mexico City around World War II, including those whose work she found in 2005. She says that there are many people in the United States who see Mexico as peripheral, instead of inextricable from our own identities, and she uses her platform to debunk that perception.

As an example, Beth cites a print made in Mexico City in 1942 by Leopoldo Méndez. His linocut shows Jews being loaded into boxcars, which she describes as an early image of the Holocaust—especially for this side of the Atlantic. She emphasizes how Mexico has never been peripheral to modern geopolitics, and believes the print itself reverberates with interconnectedness. “I’m related to survivors [of the Holocaust],” says Beth, “and [this image proves] we didn’t suffer alone, that some people were paying attention.”

When asked about Elizabeth Catlett, Beth refers enthusiastically to her illustrated series “I Am the Black Woman,” which was included in the collection Beth found. She admires this series because it highlights Catlett’s technical virtuosity, and also her cleverness in depicting political and personal pain, which often involves using a sense of irony to get an idea across. Beth explains, “There’s one print where [Catlett’s] caption is ‘I have special reservations,’ and beneath [the phrase] is an image of Rosa Parks.” Parks, a leading civil rights activist of the 1950s, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white person; she didn’t have “special” reservations at all, which, Beth suggests, was exactly Catlett’s point. “These prints were made 75 years ago, and they could have been [made] today, 100%,” Beth notes.

Artwork by and for people of color is often not given the attention it deserves in college classrooms, which is a systemic failing Beth says she wants to change. Almost half of Beth’s students identify as Latinx, which has motivated her to build art history curricula so that students from underrepresented backgrounds don’t feel pressure to “code switch” in the classroom—that is, don’t feel pressure to act or speak one way at school, versus another way at home.

Beth, who lives in Houston and is married with two daughters, says she tries to instill in her children a similar ideal of inclusion. “I hope my kids [become] people who see [others] who are different from them, and make space for them [to thrive],” she says.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.