Wellesley for Black Students and the Native American Student Association each issued lists of demands amid nationwide protests over the summer.

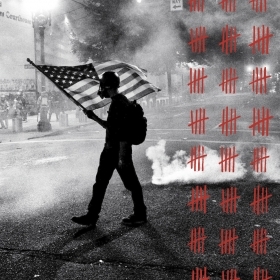

Illustration by James Steinberg c/o theispot.com

When the academic year began in August, the Wellesley community was met with many changes—but not all were due to the global pandemic. Some of them, including a new living corridor for Black students called Walenisi, and some changes at the Wellesley College Police Department, resulted from a list of demands issued in June by a coalition of students of African descent at the College as protests swept the nation.

Wellesley for Black Students began as a group chat among students of African descent, who then sent out a questionnaire via Google forms asking Black students what they would like to see changed at the College. Then, the students divided the demands, 21 in all, into categories: policing (including that Wellesley abolish campus police and immediately disarm officers); academics (including that the College hire more tenure-track Black faculty and invest in and expand the Africana Studies department); and student life (including that Wellesley increase the number of Black students on campus to 12 percent from the current 5.9 percent, bring back Black student orientation, and establish Black student housing).

As Wellesley began the academic year in late August, President Paula Johnson wrote in a welcome-back letter to the community, “Together with Dean Sheilah Horton and Dean Joy St. John, I have met with [Wellesley for Black Students] twice during the summer, and a broader group has been working to make progress on a number of issues to more aggressively advance our institutional goal of achieving inclusive excellence and, more explicitly, working to dismantle structural racism.”

Johnson noted that Police Chief Lisa Barbin left the College in July and said that Wellesley will use this “transitional period as an opportunity to explore the vision of public safety we would like to have on the Wellesley campus.” This effort will include focus groups of students, faculty, and staff to listen to ideas and concerns regarding public safety on campus. Johnson also said that the administration is working to address how the curriculum will embrace multiculturalism, efforts against racism, and social justice in both a national and global context, and pointed to the Division of Student Life’s “Twenty-One Days Against Racism Challenge,” a program to engage students and staff in the fight against racism in their various spheres of influence. She also stated that the College had received a philanthropic gift to allow it to establish an Office for Student Success, which will be the umbrella for “many of our programs focused on ensuring the success of each of our students, with a particular emphasis on our FGLI (first-generation, low-income) students.”

Paige Feyock ’22, vice president of Ethos and one of the original organizers of Wellesley for Black Students, says she is excited by the demands that have been met so far, but emphasizes that the group’s main goal for this academic year is the abolishment of campus police. The executive board of Ethos is also working hard to maintain a sense of community, even with its members spread across the globe, with both virtual and in-person, socially distanced events. “We are hoping that we can use this time to reinstitute a sense of siblinghood among our members and really focus on fostering good relationships when people seem to feel so disconnected from one another,” Feyock says.

In late August, Wellesley’s Native American Student Association, led by its president and founder, Kimimilasha “Kisha” James ’21, issued its own set of demands to College administrators, covering topics including institutional accountability, curriculum and hiring, student life, and admission. This semester, the administration is meeting with the students to discuss their demands, including their request for a College land acknowledgement.