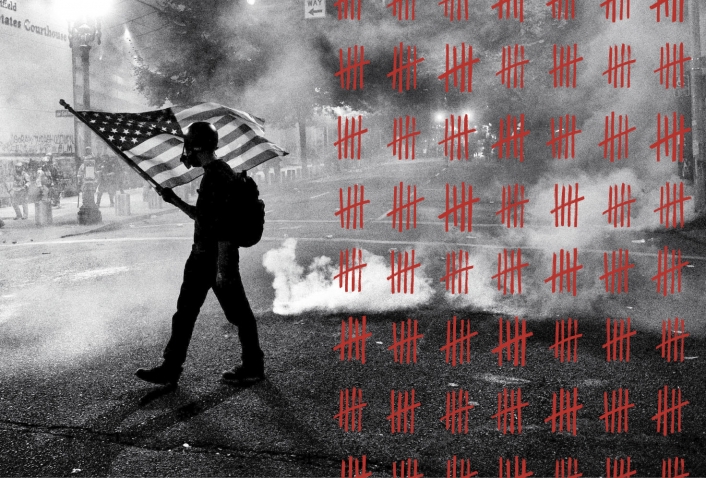

On July 21, a Black Lives Matter protester carries an American flag as tear gas fills the air outside the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse in Portland, Ore.

Photo by Noah Berger/AP Photo

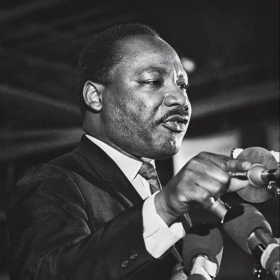

Kellie Carter Jackson, the Knafel Assistant Professor of the Humanities and an assistant professor of Africana studies at Wellesley, studies slavery and the abolitionists, violence as a political discourse, historical film, and Black women’s history. As protests erupted across the country this year, Carter Jackson became a sought-after speaker and writer for national media outlets, offering her perspective on the role that violence has played in the pursuit of civil rights, as she does here.

M

any Americans are invoking the Civil Rights movement as a model for today’s efforts to create systemic change. We cherish stories of that time as we do comfort food. But there is a lot of warped nostalgia about the movement. We want to roll tape of protesters walking arm in arm singing “We Shall Overcome” and forget how often the Black people leading the movement were overcome—attacked by dogs, trampled, hosed down, and even murdered.

Our diluted version of how change happens is ahistorical at best and, more alarmingly, gives a false model for how to accomplish reform. The political gains of the Civil Rights movement were significant, but they did not happen without violence and struggle, and even then they didn’t begin to address economic inequity, which is at the core of inequality and racism. If Americans want to see substantive change, history suggests we go back further to find a blueprint.

Troy Gayle holds his son, Julian, 5, while listening to his wife, Latoya, speak during the March Like a Mother for Black Lives rally at Copley Square in Boston on June 27. Latoya Gayle was one of the organizers of the event.

Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

No other time in American history shows what it takes to achieve major change more than the fight to abolish the institution of slavery. At the start of the Civil War, more than 4 million Black people were in bondage. One in three Black people faced separation from their families at the auction block. Black people’s life expectancies were inextricably tied—inversely—to the market. When cotton prices were high, life expectancy for Black Americans shortened. Enslaved people were property. Abolitionist Theodore Parker put it plainly: Black people were “things”; they could be “damaged but not wronged.” The only way America overthrew this violent and oppressive system was through the Civil War.

The abolitionist movement was founded on peaceful principles. Many white abolitionists believed that they could persuade slaveholders that slavery was morally wrong. White abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, believed in a “turn the other cheek” ideology. But throughout the antebellum period, free Black Americans saw their churches, businesses, and schools destroyed by white mobs seeking to preserve the status quo: Black subordination. During the time of the abolitionist movement, not only were runaway slaves tracked down in the North and returned to bondage through the Fugitive Slave Law, but the Supreme Court declared that even free Black people “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Some in the movement realized it would take more than persuasion to abolish slavery. As the white Quaker abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster put it: “Since slavery was maintained by force, it might justly be opposed in the same way.” She added, “The question is not whether we shall counsel the slaves to forsake peace, and commence war; the war exists already, and has been waged unremittingly ever since the slave has been in bondage.” And to be clear, Black America did not start the conflict.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.