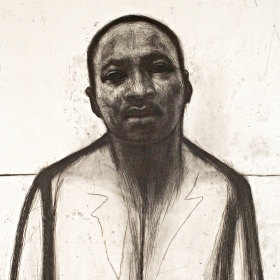

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking in Memphis on the eve of his assassination in April 1968.

Photo by Bettmann/contributor/Getty Images

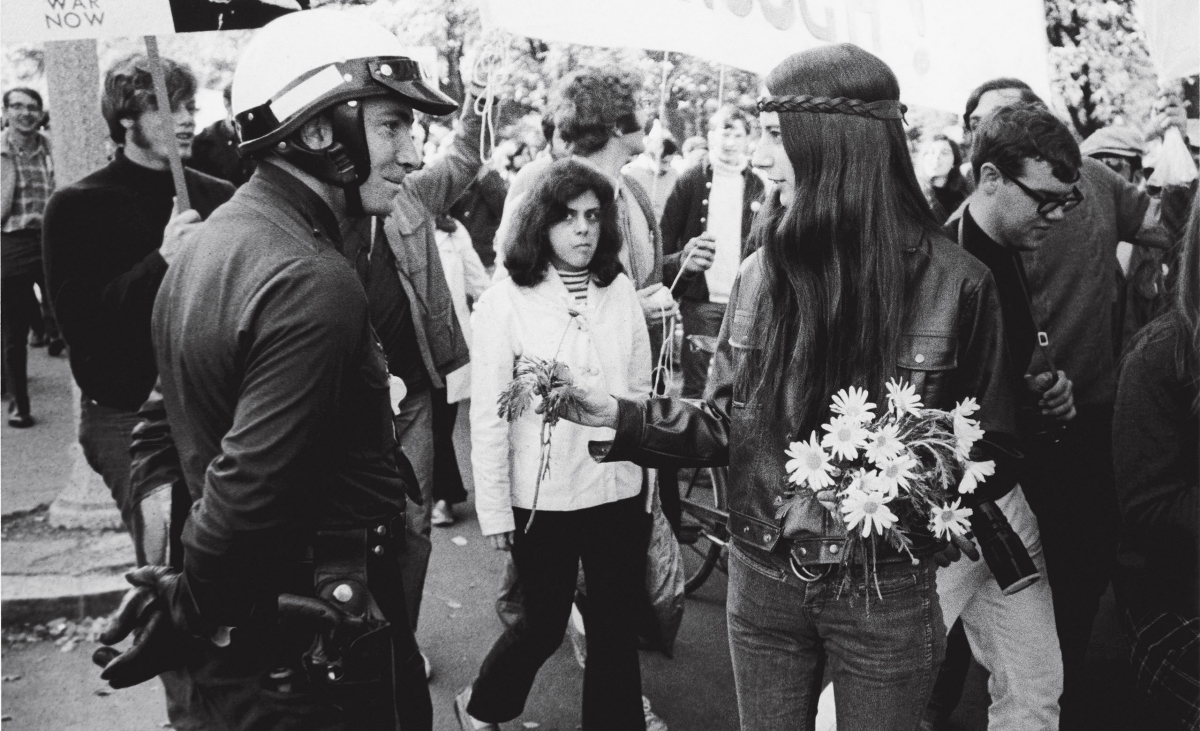

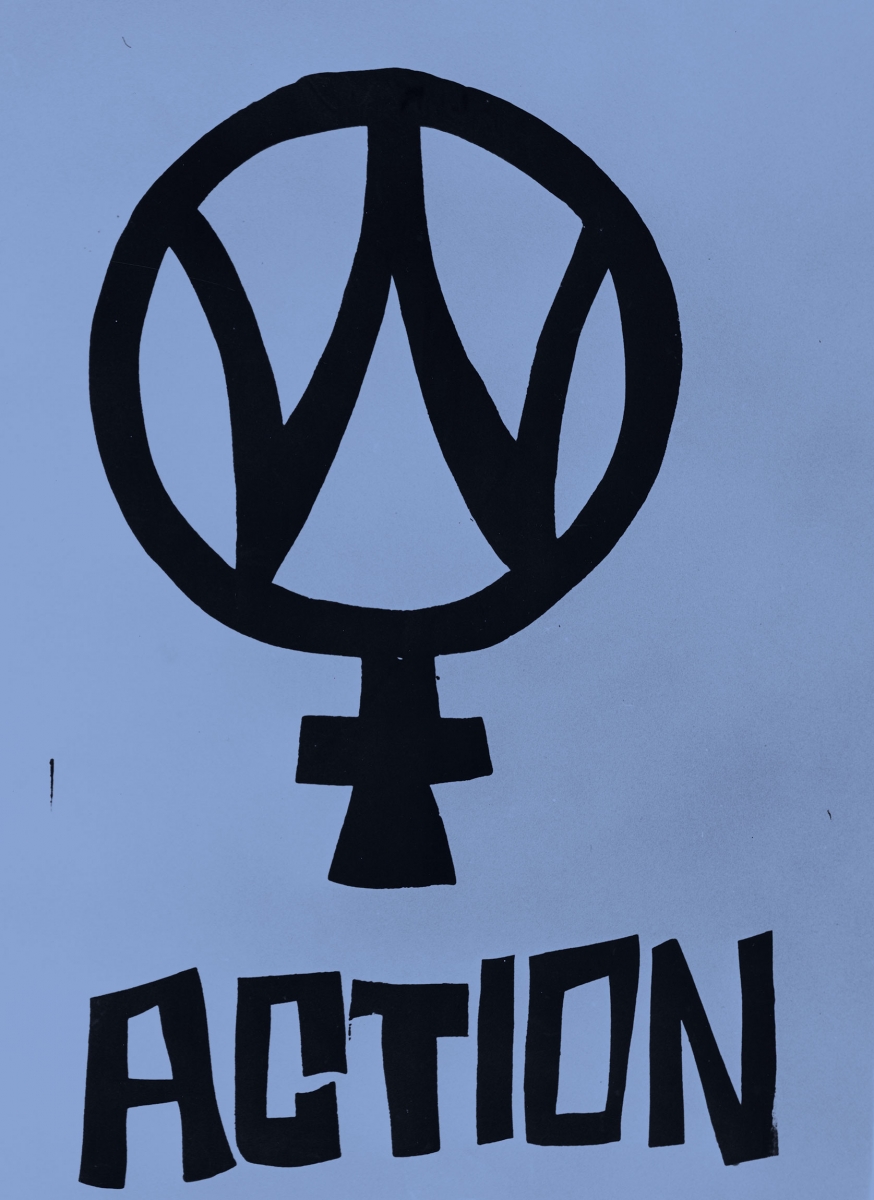

Fifty years ago, the conflict in Vietnam was raging, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy stunned the nation. Civil-rights marches, anti-war protests, and riots were bringing thousands into the streets across the country. Out of this tumult came profound new directions for the United States—and for alumnae who came of age in that era.

Callie Crossley ’73 remembers the advice her father gave her as she got out of the car at her new high school, Memphis Central, in the late 1960s: “If anybody puts their hands on you, I want you to shove them into the locker and run like hell.”

Fifty years ago, Crossley was among the first wave of African-American students to integrate Memphis City Schools. She was one of 19 African-American students who integrated Memphis Central.

Despite what her father told her, Crossley doesn’t remember being frightened. She was mostly curious about “what it would be to be a minority” in school for the first time in her life. But she was not oblivious to the enormous changes happening around her—in her city and beyond.

Memphis sanitation workers were on strike for fair wages and better working conditions, drawing on Martin Luther King, Jr., for support. It was in Memphis that King was assassinated in April 1968—Crossley’s junior year in high school—sparking protests and riots in her city and across the country.

Memphis City Schools had remained segregated well into the 1960s, even following the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision. As part of a desegregation effort, civil-rights organization NAACP turned to local families to volunteer their students. They looked for students with strong academic records, Crossley says, because they “knew it would be emotionally upsetting.” So Crossley’s parents volunteered her, a bookish girl who had been involved in the NAACP Youth Council.

“I honestly don’t know why they agreed to let me be part of this experiment,” she says.

Crossley’s time at Memphis Central was painful, but she made friends at the school, including a good friend who was Jewish. She was involved in student activities and became the first African-American columnist at the newspaper. Still, Crossley says, there was a constant, palpable tension, and she was specifically targeted by a boy in two of her classes. “He would just go at me verbally,” she says. “Everyone would sit in the room and say nothing, and the teacher would stand outside the door so she didn’t have to witness it or intervene.”

She remembers feeling relief as her bus home would pull into her neighborhood after she had been “geared up with armor every day.”

Crossley’s story is one of thousands in a remarkable generation that ushered profound social change into the country. Wellesley alumnae who came of age in 1968 and the years surrounding it remember it as a time when everything was questioned—government, institutions, and their own beliefs and values. It was a time of deep anxiety and great idealism about the future.

The Vietnam War raged, drawing increasing criticism in the United States. King’s death stunned the nation. Bobby Kennedy—a man devoted to civil rights and unity who was poised to become the Democratic nominee for president—was assassinated nine weeks later. After a tumultuous primary and convention season, Richard Nixon was elected the nation’s 37th president that November.

But in all that upheaval, opportunities opened for people who had been disadvantaged—especially women, workers, and people of color.

The Wellesley community was forever changed by those years—in big ways and small. Some, like Crossley and fellow journalist Lynn Sherr ’63, forged paths that generations after them would follow. Others protested for women’s and labor rights and against the war or made social causes their life’s work.

‘We Don’t Hire Girls’

After graduating from Wellesley in 1963, young journalist Sherr tried to get a job in New York. “Literally every white male newspaper editor told me and all of my colleagues ‘we don’t hire girls.’ And it was just that simple.”

Young male graduates were being hired as junior reporters, while women were hired to be on the clip desk—literally clipping articles and putting them into folders.

Sherr described those limited opportunities this way in a 1997 commencement address at UMass Boston: “Glass ceiling? We weren’t expected to raise our eyes above the pile of folders on our desks.”

But the institutional changes that began in 1968 allowed Sherr to do what she knew she wanted to do and charted the course for her professional career.

By 1968, Sherr was working at the Associated Press creating films for classrooms. In that capacity, she covered the national political conventions. The Republican convention mostly proceeded as planned, but the Democratic event in Chicago descended into what she describes as “pure chaos,” inside and out. After the death of Bobby Kennedy, the party had no clear nominee. Outside on the streets, tens of thousands protested the Vietnam War and violently clashed with police.

It was an extraordinary time—and a crash course in democracy and the anger people felt with institutions. It also quickly became a turning point for Sherr’s journalism career. “I understood what was going on in the world, and I got to take part in it,” she says. “And I got to explain it to others, which is why I’m a journalist to begin with.”

The following year, the Associated Press began organizing a team of five reporters to cover race and gender, and Sherr became part of it.

It’s hard to imagine a time when issues relevant to women, anti-war activists, African-Americans, and young people were not routinely covered in the press. Stories about breast cancer or black activists were not mainstream. But the upheaval of ’68 led the head of the AP to realize that the issues those communities cared about were worthy of coverage.

Though Sherr already knew she wanted to be a reporter, she says 1968 “made my bosses understand that they needed people like me to be reporters.”

In 1970, she joined a team called “Living Today,” which became known as the “Mod Squad.” Sherr mostly covered the women’s movement and activist Abbie Hoffman. She wrote one of the first major national stories on the ecology movement, and she interviewed young leaders of the Republican party. One of her most memorable stories was on the use of a strange new term—“Ms.”

“Our assignment was basically to go out and explain this crazy new world to our readers,” she says. “All these things were a great awakening. In terms of awakening my feminist consciousness, it changed my life forever.”

Investing with a Conscience

Elsewhere in New York, Alice Tepper Marlin ’66 was changing a different storied American institution—Wall Street. She remembers the events of 1968 as “a real shock, [which] jolted a lot of us.”

That year, Tepper Marlin was working as a securities analyst—rare for a woman on Wall Street—when she received an unusual request. A portfolio manager of a synagogue did not want to invest in companies supporting the Vietnam War.

Back then, most consumers did not vote with their wallets and investment portfolios as they do today, ever conscious of who supports the causes they value or loathe.

When Tepper Marlin created a “Peace Portfolio” for the synagogue, the concept of corporate social responsibility began to take shape. Her firm took out a small ad in the New York Times inviting others to create portfolios based on shared values. They received 700 responses. “I started talking to those people,” Tepper Marlin says, “and determined there was a real market.”

But she had trouble finding the information to help her clients determine whether where they invested lined up with their values. Beyond the war, she says, “I wanted to expand this idea to civil rights and the environment.” So she started her own organization to provide that research, founding the Council on Economic Priorities in 1969.

Corporate and consumer social responsibility became her life’s work, rooted in the social causes that bubbled up in 1968.

For decades, CEP researched social and environmental issues and eventually broadened out from Wall Street investors to guiding the general public. The council developed and morphed into Social Accountability International, and Tepper Marlin is now president emerita.

‘A Radically Different Path’

The changes of 1968 were also palpable on campus. The year put Sally Giddings Smith ’68, like many of her classmates, on a “radically different path” than the one she had imagined for herself.

Smith remembers spending hours in her residence hall as a Wellesley senior discussing politics, relationships, and more with her classmates. Some of those talks would come to inspire tremendous shifts in the consciousness of women on campus and for the campus itself during those years.

“It was a time of awakening to real issues for all of us—from civil rights to Vietnam. I can’t think of any one of us that escaped the impact of those years,” she says.

“We spent hours in that [Shafer] suite… ,” she says. “We would have endless arguments, political and otherwise, endless discussion about relationships and how long and how far do you go.”

On the surface, Smith says, her class experienced the “hippie-dippy stuff” of the ’60s—their skirts got shorter, they went barefoot. But the deeper changes are the ones that have stayed with them 50 years later.

In reality, it was also a “deadly serious” time, especially on Wellesley’s campus, Smith says. “Most of us knew young men who were wrestling with what to do about Vietnam. That was a life-and-death issue. The frivolity and the summer of love stuff that was going on in San Francisco really was not relevant to us.”

The traumatic national events that year, including the deaths of King and Bobby Kennedy, became “lightning rods” for her class, she says.

Those leaders’ altruism and desire for change deeply affected students on campus. “It became very important for most of my friends to do something meaningful with their lives and not simply follow the path they had started on,” she says. “It became very important to become very meaningful.”

Across campus, there were strikes and workshops to educate about and protest against the Vietnam war, racial oppression, and the draft, as well as peace marches in the town of Wellesley. A group of African-American students had created Ethos two years before, and they were challenging the administration to increase the number of black students, faculty, and staff on campus and threatening a hunger strike. The College administration relaxed rules around when and where visitors from off campus were allowed in residence halls. And students participated in activism off campus, raising money for the Poor People’s Campaign’s march on Washington and supporting other causes.

Students took “question everything” seriously. A November 1968 article in the Wellesley News describes inquiries into the source of the grapes served on campus after news of a nationwide grape boycott.

Smith herself had wanted to become an architect, but found herself drawn to education. Teaching was a traditional path for women in her family, but she became what she describes as a “radical educator.” It was a tumultuous time for Boston city schools, as controversial school board member Louise Day Hicks staunchly opposed desegregation through busing.

So Smith worked at informal “street academies” in Burlington, Vt.—cobbled-together schools for students who had dropped out. She taught one class called Street Marxism. “We would just walk around the city of Burlington,” she says, “and speculate based on the history on what we were seeing. We learned to analyze neighborhoods.”

She went on to become a longtime advocate for children, directing group homes for troubled children and serving in local politics and on school boards in Vermont and as political chair of a governor’s committee on children.

Smith says she has seen that kind of commitment to service in just about everybody she knows in the class of 1968. “I think it really did change a lot of our lives and our directions.”

Regular Kid to Labor Organizer

Like Smith, Laurie Sheridan ’66 recalls being at Wellesley during a time when students had to wear skirts to class and follow a certain protocol. Sheridan entered Wellesley as a “regular middle-class kid.” She was very serious about her studies and laying the pathway to an academic career, not particularly involved or interested in politics. But by the time 1968 came, just a couple years after she graduated, “the whole world kind of split open.”

The Vietnam War affected her deeply—she had friends from high school being drafted and watched as dead soldiers were shipped back home. “I just felt the world turn upside down for me, and I didn’t trust anybody or anything anymore. Everything I had been told about war and patriotism and about my country had been lies,” she says.

Sheridan remembers having “big arguments” with her family over these issues. And while she says there were others who were more progressive and radical than she was, she so strongly opposed the Vietnam War that she left graduate school to demonstrate full time against it.

She started studying imperialism and politics and says she became an activist “in a way that no one in my family had ever been.”

It was a time when “everything was being questioned,” she says. “It was almost like I became a different person in a shocking way.”

Sheridan went to work as a factory machinist. The thing that really “grabbed me by the throat” in 1968 and later was working with women in factories, whose lives were so different from hers. She went on to become a lifelong labor and union organizer, helping women, people of color, and immigrants learn their rights, and an advocate for better child care.

1968, she says, raised “all the issues that I carried with me through life—child care, family and medical leave, getting good jobs, being healthy and safe in the workplace.”

Valuable Lessons

Crossley, now an award-winning radio and television host and commentator, says it was traumatic to be part of Memphis’ school integration experiment in the 1960s. But she still carries the memories of those years that changed her irreversibly—in some ways for the better.

“I was a completely different kid going in and coming out,” she says. “Talk about learning to speak up—that was my speak-up training right there.”

Every one of the African-American students who integrated Memphis Central that year got college offers, she remembers. Crossley, of course, went to Wellesley, which she credits with helping her more deeply find her voice.

She carries a profound gratitude for all the other people who stood up to effect change in those years—and she has an enduring modesty for her own part in it. All around her, Crossley says, “people were making greater sacrifices.”

Now, she says, she feels a responsibility to them. “I recognize very well that I’m privileged in many ways,” she says. “People literally gave their lives … so I could sit in this chair. I am keenly aware of that, and I don’t ever forget it.”

Sherr believes the country can also draw valuable lessons from the movements of 1968.

The major lesson from those years, she says, is to “listen to the revolutionaries. Listen to the complainers. Listen, because while everything might not be right, at least there’s something there, and something good can come out of it.”

But she acknowledges that listening to the complainers can be complicated in today’s divided political climate.

“It was just such an important time,” Sherr says. “Was it all perfect? Absolutely not. Were there stupid and dumb things that were done? Of course.”

Much of the change back then was “very good. Some of it was just too much too fast and too glib,” she says. “But sometimes things, as you know, have to get broken before they get fixed.”

Amita Parashar Kelly ’06, an editor on NPR’s national desk, is grateful for the endless opportunities she has had, thanks to the generation that questioned everything.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.