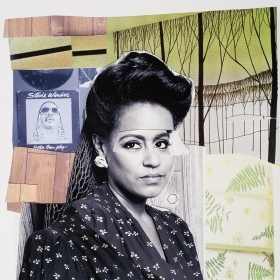

Alumnae who have spent time on the East Side (previously known as the New Dorms) will have passed Persephone, a freestanding sculpture by Bates’s entrance, and Demeter, a carved relief panel accompanied on its back side by a third panel depicting oak leaves, closer to Freeman.

Persephone, 1952, Alabama limestone, carved

Photo courtesy of Wellesley College Archives

Alumnae who have spent time on the East Side (previously known as the New Dorms) will have passed Persephone, a freestanding sculpture by Bates’s entrance, and Demeter, a carved relief panel accompanied on its back side by a third panel depicting oak leaves, closer to Freeman. I lived in McAfee my first year, and for me these works became part of the passing scenery that enlivened the beautiful campus. Their historic connection to the space reflects a thoughtful engagement with college life as a space for growth and independence.

The artist who created these works, John Rood (1902–1974), was an established midcentury sculptor who spent much of his career teaching art at the University of Minnesota. His early education and professional interests included a transformative trip to Europe, where he mingled with the Parisian avant-garde, and the creation of a literary magazine, Manuscript, which he edited with his first wife. In the late 1940s, he married Dorothy Bridgman Rood, Wellesley class of 1910.

Through his wife’s connection with the College as a trustee, Rood was engaged to create an outdoor sculpture for the new complex of dorms. In an article he wrote for this magazine in November 1952, Rood described how he developed his concept for the sculptures. He talked with the architects and studied the plans for the new construction, and he also made a series of preliminary sketches and maquettes to envision how the form could be situated within the plaza. In the summer of 1952, the couple spent several weeks at the College while Rood finalized details for the works ahead of the dedication for Bates and Freeman halls that September.

According to the Greek myth, Persephone may enjoy the natural world with her mother, Demeter, for part of each year, but she must return to the underworld during the winter months. The ancient narrative explains the seasons’ cycles of growth and decay: Persephone warms the earth with her arrival each spring and Demeter joyfully activates a season of growth, followed by a season of darkness and cold as Demeter mourns the forced separation from her daughter. Rood’s choice to depict this story on the Wellesley College campus foregrounds the importance of female relationships and the powerful connections between women and the natural world.

The towering form of Persephone is carved in the round, and it is meant to be viewed from all sides. Large leaves create a wide base, from which rise four thick columns that meet at the top. The edges of their undulating shape defines an abstract female form in the negative space—the young Persephone materializes among the carved depictions of plants and animals on the columns’ surface. As the viewer walks around the sculpture, the open void that represents Persephone is filled with distant sky and green trees, or the bright glass and brick geometry of the nearby architecture. Rood described struggling with how to depict the myth’s main character, as well as communicate the temporal narrative. In his 1952 article, Rood explained, “At last I hit upon the idea of enclosing the figure within the stone, so that the space itself becomes the figure of Persephone.” Her identity is both trapped within the heavy stone, yet also liberated as a universal presence made of earth and sky.

Persephone and Demeter were among the first public outdoor artworks to be permanently installed on campus. These works, as well as more recent additions such as Kenneth Snelson’s Mozart III, near the Science Center meadow, or the woodland installation by Michael Singer and Michael McKinnell along the lake path, not only enrich our visual experience, but also serve as historic markers in the long arc of Wellesley’s engagement with art and landscape.