1920–2024

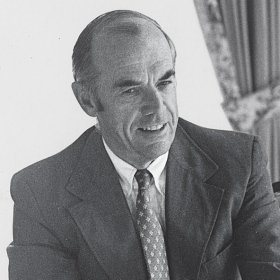

The “Boston gentlemen” have played a key role throughout Wellesley’s history. Henry Durant, the Hunnewells, the Kidders, the Stones, and others were the movers and shakers downtown who brought their time and talent to Wellesley to build and strengthen the world’s exceptional college for the education of women. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., was one of those gentlemen.

The “Boston gentlemen” have played a key role throughout Wellesley’s history. Henry Durant, the Hunnewells, the Kidders, the Stones, and others were the movers and shakers downtown who brought their time and talent to Wellesley to build and strengthen the world’s exceptional college for the education of women. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., was one of those gentlemen. He was also devoted to his wife, Ruth, and their six children. He lived a rich and fulfilling life until his passing on June 18 in Swampscott, Mass., at age 103.

When Nelson joined the Wellesley College Board of Trustees in 1963, he brought a wealth of experience from his education at Harvard University and Harvard Law, his service as an officer in the U.S. Navy during World War II, and his time practicing law at Ropes & Gray followed by a career in investment banking at Paine, Webber, Jackson and Curtis. His Boston service included chairing the Boston Symphony Orchestra board and working on the board of Massachusetts General Hospital. Nelson served the College contemporaneously with the Vietnam War and the expansion of civil rights.

Under President Ruth Adams, Nelson was chair of the Structural Revision Committee, which examined College governance and the relationships of College Government, Academic Council, and the board of trustees, and he made recommendations that remain in force today.

The second key committee of that era was the Commission on the Future of the College. Nelson took on the responsibility of chairing the Wellesley board shortly before the commission reported its five recommendations. The board accepted four of the five. With respect to the fifth, the board voted, as a minority of commission members also had, that Wellesley remain a women’s college. Ever the cautious lawyer, he suggested Wellesley reexamine that premise every decade or so to see if the decision was still the right one.

His family noted that “being involved with educational institutions gave him the opportunity to engage across generations to explore the critical questions of our time.” Indeed, Nelson was at the forefront of another generational shift as he was the last male chair of the Wellesley board. He passed the baton to Betty Freyhof Johnson ’44 in 1981, near the conclusion of his service. But his love for and commitment to Wellesley never dissipated. Wellesley, and its mission, remained one of his philanthropic priorities until his death. Nelson was known for his wisdom and consensus building and for hearing all sides before acting. And he recognized and understood the true and enduring vitality of Wellesley, observing that “probably the greatest strength of Wellesley College is the accumulated strength of the alumnae group.”