We are the storytelling species, and how we tell our stories shapes our reality. During the past academic year, a small cadre of Wellesley students had an opportunity through the College’s new Narrative Lab to look deeply into how narratives are constructed and the ways they create meaning.

In the Narrative Lab, faculty and students come together to study narrative theory and narratives across all periods, genres, and media, from ancient texts to video games. In 2024, the Mellon Foundation awarded Wellesley $1.5 million for its proposal, “Transforming Stories, Spaces, Lives: Rethinking Inclusion and Exclusion through the Humanities.” The Narrative Lab is one aspect of the three-year TSSL program.

The lab invites several students each semester to engage in research to learn and apply narrative theory. They meet weekly with a small group of faculty from humanities departments, including Josh Lambert, Sophia Moses Robison Professor of Jewish Studies and English, and Erez DeGolan, a Mellon postdoctoral fellow in Jewish studies. These Narrative Lab fellows are paid the same rate as work-study students for five hours a week over 12 to 14 weeks; they don’t receive academic credit. Initially conceived as a standalone initiative, the lab was later integrated into the broader TSSL effort to engage undergraduates in humanities research. This fall, the lab will be housed in the new Humanities Hub in the renovated Clapp Library.

Narrative theory examines how narratives function and the distinctions between story (the events) and discourse (the telling of those events). It explores aspects like point of view and understanding narrative as a rhetorical act aimed at an audience. Moving beyond text on the page, the approach is used to interrogate media like TV, film, video games, and social media. Narrative theory isn’t simply a literary exercise; it looks at how narratives are created, adapted, interpreted, and put to use in the world in fields such as medicine, psychology, and even strategic planning for businesses.

“Narrative theory focuses on stories and storytelling. It examines the structure and the function of narrative very broadly defined, and it is focused on generating useful and applicable concepts that allow us to identify and describe the workings of narratives,” says Yoon Sun Lee, Anne Pierce Rogers Professor in American Literature and professor of English, who led the lab in its first year. “The foundational distinction is between story and discourse, or story and text, which means what actually happens in a narrative versus the way in which it’s told.”

Lee says she first got the idea for a narrative lab in 2021, after many years of teaching narrative theory in the First-Year Writing Program and seeing students get really excited about its concepts. “While my first proposal in 2021 for a Mellon grant for a narrative lab did not get funded, I wrote it into the larger 2024 proposal that did win a grant,” she says. The project offers students in the humanities opportunities to do hands-on research with faculty involvement, just as they might in the sciences.

Four students were Narrative Lab fellows in the fall 2024 semester: Megan Rodriguez-Hawkins ’25, Tsering Lama ’27, Eunice Zhang ’27, and Marina Escandell-Tapias ’28. In April, they presented their projects at the Ruhlman Conference, Wellesley’s annual celebration of student achievement, which “offered a valuable opportunity to showcase their evolving research,” Lee says.

The Narrative Lab began with “a brief crash course in the fundamentals of narrative theory, after which students transition into reading more advanced, field-specific applications, such as those involving video games or television,” Lee says. Then, the fellows began their journeys.

Pain without a plot

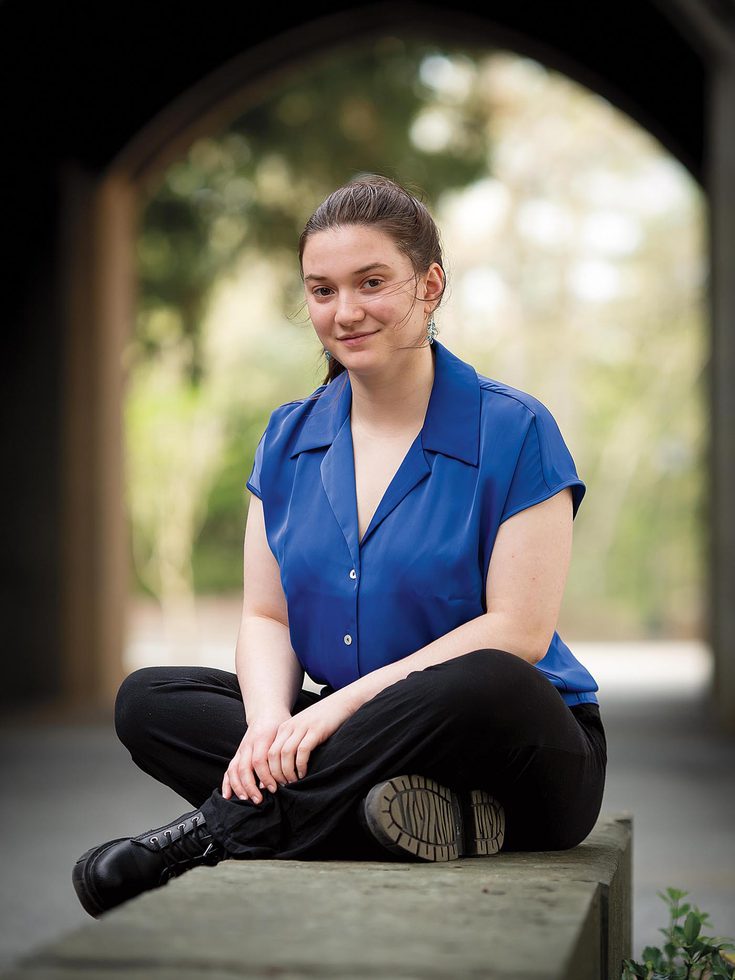

Marina Escandell-Tapias applied for the Narrative Lab after she didn’t get into her first-choice writing class with Lee, ENG 106: Narrative Theory and Social Justice. A prospective English and creative writing major, she did her project, “Memoirs in Pain Narrative,” on how women write about chronic pain. She used narrative theory to analyze how writers present the self in memoirs. She was particularly interested in the concept of the “real” versus the “implied” author—that is, the flesh-and-bone person who wrote the text versus the person the reader imagines as the writer.

In her Ruhlman presentation, Escandell-Tapias explained that a key text informing her research was Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain, which argues that pain is inherently incommunicable. “Narrative theory, however, offers tools to work around this limitation,” Escandell-Tapias said, adding that pain memoir defies traditional narrative arcs and resists neat resolutions. “Pain becomes an ongoing presence, not a story with a tidy ending,” she said. “I focus[ed] on three memoirs: A Body, Undone by Christina Crosby, which explores time and identity after paralysis; Pain Woman Takes Your Keys by Sonya Huber, which uses fragmented storytelling to reflect chronic pain’s ruptured nature; and The Tiger and the Cage by Emma Bolden, which critiques medical misogyny and loss agency.”

Lee was in the audience at the Ruhlman presentation, and says she was impressed that Escandell-Tapias had “continued to polish and work on her project,” even after the lab concluded. “I’m really impressed with what she did,” Lee says. “At first, her ideas were so broad. She wanted to do something about pain, but that subject is a vast area. It’s hard to know what kinds of questions you can ask about it. But by the end, she raised some very interesting questions about the relationship between pain and narrative and narrative structure.”

Escandell-Tapias grew up in Iowa, and when it was time to select her next step, “I wanted a small college with intimate classes, and with the Narrative Lab I got more than I expected,” she says. “There were just the four students and three professors getting together on Fridays in the afternoon in Founders to talk about our projects. I got to be in an intensive class and get paid!”

More than story time

Tsering Lama, an economics major from New York, also turned to literature for her project. She proposed case studies of the beloved children’s classics Charlotte’s Web, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Little House on the Prairie, analyzing how indirect narrative techniques in the books reflected dominant Western ideologies during the Cold War.

“All three works employ indirect presentation, where themes and character traits are shown through actions, environment, and symbolism rather than stated outright,” she said at the Ruhlman Conference. For example, in Charlotte’s Web, Charlotte sacrifices herself to save Wilbur, illustrating themes of friendship and selflessness. “These ideas parallel the U.S.’s Cold War strategy of forming alliances with smaller nations, positioning itself as the underdog against a more powerful adversary, much like Wilbur. The use of an omniscient narrator and vocalizers, like Wilbur, deepens the emotional and ideological messaging,” she said. “These texts show how narrative tools like indirect presentation and setting conveyed political themes to young readers.”

Lama applied to the Narrative Lab because she was interested in the relationship between storytelling and historical memory, “even though I didn’t fully understand what narrative theory meant at the time,” she says. Through the lab, she learned how narrative techniques can be used to shape perception, and how powerful those tools are—especially now, when book bans and censorship are rising, she says.

While working at Wellesley’s Child Study Center, the laboratory preschool at the College, Lama realized how children’s literature that acknowledges topics like race and inequality can affect young readers’ understanding of society. “That made me see literature not just as stories, but as tools of social influence and education,” she says.

Lama hopes to minor in history, she says: “Doing the Narrative Lab and learning about narrative theory spurred me toward history, because it showed me how to see very different perspectives that I didn’t know about before. And I think it’s interesting to apply it to my life, as well. When I’m reading the news, I’m thinking, ‘What is the narrative? What are they not telling us?’”

I would say that most people are familiar with narrative theory. I think they just don’t have the language for it ...”

Insert audience here

Megan Rodriguez-Hawkins, an anthropology major, came into the lab knowing exactly what she wanted to investigate. “I proposed a research project exploring narrative theory, character types, and audience relationships, focusing on the character Abed Nadir from the sitcom Community,” she says. “My central question was: What kind of character is Abed, and how does he shape the narrative and viewer experience?”

Abed processes life through the lens of TV. He often interprets real-life events using TV references, which blurs the line between character and audience, Rodriguez-Hawkins explained in her Ruhlman talk. “Some fans describe him as an ‘audience surrogate’ or ‘self-insert’ character. I argue he is best understood as an ‘audience insert’—a hybrid who mirrors audience reactions while influencing the story’s direction,” she said. “This matters because these characterizations impact how we understand storytelling and engagement.”

Rodriguez-Hawkins says she started watching Community, a sitcom set at a community college, with her older brother when she was growing up in Connecticut. “He’s about 10 years older than me. When I was youngish, he introduced my twin brother and me to Community, and we’d watch it as a way to bond,” she says. At Wellesley, she started watching the show again with friends who turned out to be as obsessed with it as she was.

Was Rodriguez-Hawkins familiar with narrative theory before she applied to the lab? “Short answer, no. Long answer, yes,” she says. “I would say that most people are familiar with narrative theory. I think they just don’t have the language for it, or don’t understand that it is narrative theory that they’re familiar with. Because, you know, if you consume any media, you’re getting the narrative theory.” She says the Narrative Lab “opened up a window of what could possibly be in my future, if I ever wanted to dissect media or analyze media. These types of conversations are emerging within academia.”

Game over?

Eunice Zhang, a sociology major from Illinois, presented a project titled “Vault Dwellers to Ghouls: Characterization Across the Fallout Games and TV Series,” exploring how video game narratives—especially those that are player-driven—translate into fixed, passive media like television.

Video games combine passive storytelling with active player interaction, allowing players to shape characters and influence outcomes. This presents a challenge when they are being adapted into noninteractive formats like TV, where audience agency is lost. Zhang explored the issue using the Fallout franchise, a post-apocalyptic role-playing game series.

“Ultimately, my research contributes to understanding transmedia storytelling and how adaptations need not retell the same story, but instead extend and reinterpret interactive narratives,” Zhang said at the conference. “This helps us rethink how we engage with and emotionally invest in stories across media.”

Zhang says that as both a gamer and viewer she became curious about why these adaptations resonate with viewers even without the interactive element. “This curiosity aligned well with the Narrative Lab’s broader exploration of narrative forms beyond traditional literature—like sitcoms and other media,” she says. “I was especially interested in how narrative transforms across platforms and how it shapes how people understand and navigate the world.”

Zhang developed an individual research project outside of a class assignment for the first time in the Narrative Lab, and in such a small group it was a highly personalized experience. “We shared work regularly, and both faculty and peers offered feedback and ideas, helping refine our projects in meaningful ways," she says. She learned how to craft a solid research question, conduct literature reviews, and manage scope—balancing specificity with broader relevance within a semester’s time. “I’m a sociology major planning to attend grad school, so having the chance to pursue a self-directed project with faculty guidance was incredibly valuable,” she says.

Zhang definitely would encourage others to join the Narrative Lab. “It made research more accessible, especially for students without prior faculty connections. And yes, we were paid, which was great—getting compensated to explore your own ideas and interests,” she says.

A research-first approach

Josh Lambert will lead the Narrative Lab this fall when Lee is on sabbatical. He says one of the most exciting aspects of the project is the immersive and collaborative nature of the work. “Conversations often begin among faculty and expand to include students, who push and pull us in new directions,” he says.

The lab defied the traditional classroom structure. “We aimed to avoid making it feel like just another class,” he says. “Many students come into humanities courses thinking their job is simply to master the material. But scholarship is about inquiry—formulating questions, not just knowing answers. That’s the mindset we encourage.”

The lab also experimented with a new format: Instead of executing projects, students planned them. Lambert explains: “The idea we came with was, ‘We don’t want you to execute a project. We want you to plan a project. We want you to think about what project could be done. What would be useful about doing it, and what would be necessary? What kind of tools would you need? What staffing would you need? What kind of resources would you need to do a project on some piece of narrative that compels you?’”

This approach concluded with the creation of individual research prospectuses consisting of three- to five-page documents with bibliographies outlining hypothetical projects. Throughout the semester, fellows offered each other feedback and posed questions. Lambert says their conversations were often about what would work, what makes sense, what’s a good question, what’s not a good question.

The aim, Lambert says, was to have a “research-first approach, to say it’s about formulating research questions. … That’s part of the fun of the lab, of taking a student who isn’t necessarily a grizzled English major but who probably does like literature a lot, and then saying, ‘What’s the value of looking at it in this other way? What’s the value of analyzing it?’”

Catherine O’Neill Grace is senior associate editor of this magazine. Reporting this story made her rethink her understanding of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Post a Comment

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.