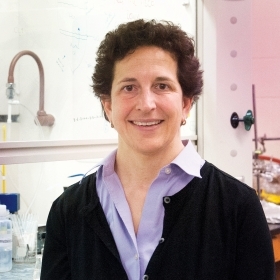

Laura Stevens ’11

Laura Stevens ’11 has spent enough time on glaciers to know what it’s like to get a sunburn on the inside of her nose, from sunlight bouncing off ice during hours of field work.

Laura Stevens ’11 sets up a GPS station on the Disko Island ice cap in West Greenland to track the ice cap’s velocity.

Laura Stevens ’11 has spent enough time on glaciers to know what it’s like to get a sunburn on the inside of her nose, from sunlight bouncing off ice during hours of field work. Each of the past three summers, Laura has spent a month on the Greenland ice sheet, where she’s hiked around lake basins installing GPS systems, stayed out late in the midnight sun, and driven remote-controlled vehicles in fjords.

Laura has been working on glaciers for four years for her Ph.D. in geophysics in the MIT/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program. She focuses on the pathways water takes from the surface of the ice sheet—from pools called supraglacial lakes that form each summer—toward the bottom where the ice sheet meets bedrock.

Changes in the amount of water that drains to the bed make the bedrock more slippery. When that happens, the ice sheet moves more quickly toward the coast—ultimately affecting the sea level, since faster flow increases the amount of ice entering the ocean as icebergs.

With climate change at the forefront of environmental discussions, Laura’s work is particularly relevant since rising temperatures above Greenland have caused more supraglacial lakes now than a few decades ago. With research like this, glaciologists can predict how future lakes might behave and how changing the speed of the ice sheet might affect the sea level.

“What gets me up a bit in the morning is having an idea that what I’m doing, while pretty esoteric because I work on pretty specific questions, has some effect on the rest of the world,” Laura says.

Laura wasn’t always interested in glaciology, but natural curiosity and an outdoorsy upbringing drew her to the sciences. At Wellesley, she majored in geosciences, and that Wellesley experience informs her research, she says.

“That ability to not be hindered by not wanting to ask questions that you didn’t already know the answer to: that was the main thing that Wellesley taught me,” she says. “It’s OK, it’s good, to ask questions that you don’t know the answer to.”

Glaciology drew Laura’s interest during a summer research program at Woods Hole after Wellesley. Glaciology is a growing field, she says, because of improvements in technology that make glacier-filled regions easier to access and observe.

That’s true for Laura’s research—her lab employs a variety of techniques. To measure ice sheet motion during lake drainage, they install GPS stations around lakes; to see the internal structure of the ice sheet, they use ice-penetrating radar systems; to study where ice and ocean meet and avoid dangerous falling ice, they use helicopters and autonomous vehicles.

“I finish a manuscript or submit a paper, and it’s like, answer one question, have 10 more,” she says. “The excitement is in the fact that the field is growing, and each time you go to a new place or try a new kind of technology, it allows us to draw a better picture of a system.”

With a year left in her doctoral program, Laura has been spending less time in Greenland and more time writing, though she jumps at every opportunity to assist in field work, like a recent trip to Botswana—where lions and heat suddenly became considerations—and an upcoming one to Antarctica.

And in this previously male-dominated field, women are becoming more prominent. “I’m entering the field at a time when I shouldn’t expect to be the only woman in a field camp,” she says. “It’s always small statistics, but it makes a huge difference.”