As senior curator of the Met’s museum of medieval art, Barbara Drake Boehm ’76 seeks to bring a lost world vividly to life.

As senior curator of the Met’s incomparable museum of medieval art, Barbara Drake Boehm ’76 seeks to bring a lost world vividly to life.

Photo by Amos Chan

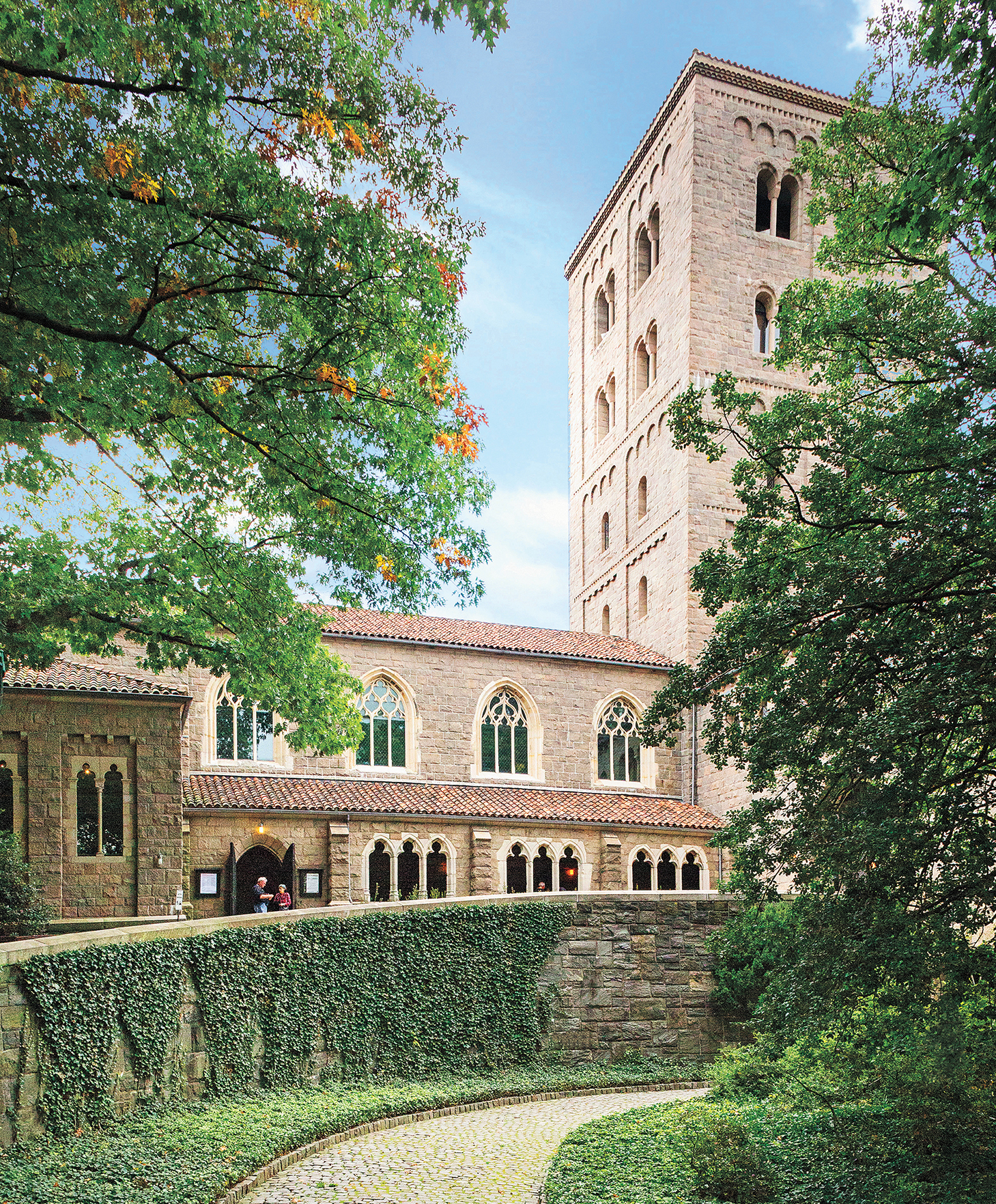

The Cloisters perches on one of the highest promontories on the island of Manhattan. From her aerie in the building, Barbara Drake Boehm ’76, the Paul and Jill Ruddock Senior Curator for the Met Cloisters, overlooks the span of the George Washington Bridge—one of the busiest vehicular bridges in the world. But Boehm’s surroundings are hushed and peaceful, more reminiscent of 15th-century France than modern-day New York City.

Although the building was erected in the late 1930s, the Cloisters evokes—and includes architectural elements from—medieval Europe. It encompasses five monastic cloisters incorporated into a modern museum structure. Displayed in its galleries are tapestries, altarpieces, metal, wood and alabaster carvings, medallions, collections of chalices and reliquaries, ivory chess pieces, illuminated devotional books, and much more.

The Cloisters building was artfully pieced together from European architectural elements, often abandoned, located by American sculptor George Grey Barnard in the early years of the 20th century. He purchased many, brought them to New York in 1913, and put them on display in a building on 190th Street. In time, John D. Rockefeller bought the pieces, as well as a large tract of land now known as Fort Tryon Park. Rockefeller donated the architectural elements and art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the park to the city. (Rockefeller also donated hundreds of acres on the west bank of the Hudson, and presented those palisades to New Jersey, thus preserving the view from the Cloisters forever.) In the 1920s, additional chapels and cloister elements were acquired in Europe and meticulously resurrected stone by stone above the Hudson to create the present building. The completed Cloisters opened its doors in May 1938. It’s now listed as a National Historic Landmark.

The Cuxa Cloister, from an abandoned Benedictine monastery in the Pyrenees, is fashioned of pink marble. The capital sculptures, created during different periods, range from simple block forms to intricate representational carvings.

Courtesy of the Met Cloisters

In her role as senior curator, Boehm oversees the Cloisters’ collections and program design and implementation, and helps lead strategic planning, project management, and operational budget development—while still curating special exhibits. She inaugurated a program of focus exhibitions at the Cloisters, including Search for the Unicorn to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the museum in 2013 and some of its most beloved treasures, the Unicorn Tapestries.

As it turns out, Boehm isn’t the first Wellesley alumna to work with the Unicorn Tapestries—or within the Cloisters, for that matter. In 1928, medievalist Margaret Freeman, Wellesley class of 1921, joined the Metropolitan Museum as a lecturer in the department of Egyptian and medieval art. When the Cloisters opened in 1938, Freeman moved uptown and got to work developing the medieval gardens and organizing music programs. By 1940, she had become assistant curator. When the director, James Rorimer, went to war in 1943, she acted as director until his return. She became curator of the Cloisters in 1955, when Rorimer moved to the Met. Freeman retired a decade later as curator emeritus.

Boehm honors Freeman’s legacy at the Cloisters—and when she discovered that the online Dictionary of Art Historians didn’t include her fellow Wellesley alumna, she wrote the entry about Freeman’s career.

On the Heights

A monastic hush pervades the museum’s galleries and courtyards—unless there’s a class of neighborhood kids arriving for a tour. Boehm, who started her career as a curatorial assistant in the department of medieval art at the Met in 1983 and moved to be a curator at the Cloisters in 2008, is committed to connecting the museum with its neighborhood.

“There’s a balance of honoring the original intention but not turning this place into an immutable shrine,” says Boehm. “There’s programming in Spanish, because there’s a significant Spanish-speaking population in the neighborhood of the Cloisters. We do programs on Sunday for people who cannot visit on Saturday for religious reasons. Historically, there’s an important Jewish community in the Fort Tryon Park area.”

Entering the edifice can be intimidating for a first-time visitor. You come in through a vaulted doorway in a stone wall, the museum towering above you, and climb a long, dimly lit stairway. Once through that passage, the museum is a revelation: The galleries open into graceful cloisters—covered, pillared walkways that surround historically accurate re-creations of medieval gardens.

“It’s very important that one be able to have the experience of coming in and entering a different kind of world,” says Boehm. “That’s what cloisters were about. At the same time, you have to have people feel welcome. We have to make sure that people know we’re here.”

The number of visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art museums—the Met Fifth Avenue, the Met Cloisters, and the Met Breuer—has been climbing steadily in recent years. In fiscal 2016, numbers reached 6.7 million for the three museums, including 283,000 for the Cloisters. But Boehm would like more people to know about—and visit—the museum overlooking the Hudson.

“When I first started here, as opposed to the mothership, I would encounter people in my hometown. I live in Montclair, N.J., just 12 miles over the bridge. And it would emerge in conversation that I worked at the Cloisters. People would say—and I can’t tell you how many times this happened—‘Oh, the Cloisters. I just love the Cloisters.’ And inevitably, that was followed by, ‘I haven’t been there for years.’ That’s the problem. Apart from anything else, we have a very active acquisitions program. You’ve missed 30 years of masterpieces! Come see.”

[supporting-images]

Small Wonders, a Cloisters exhibit of Gothic miniature devotional objects intricately crafted from boxwood, includes: a prayer bead less than two inches in diameter depicting the nativity and the adoration of the magi, with gilded silver on its exterior; and a memento mori in the form of a tiny coffin. Both objects were made in the early 16th century in the Netherlands.

Courtesy of the Met Cloisters

The Making of a Medievalist

Boehm knew she wanted to be an art historian when she was still in grade school, she says. “I didn’t really know what it was called. I have an older sister—a decade older than I am. She was in college at Smith at the time, so I could not have been more than 11. I wrote to her and I said, ‘Is it possible to study the history of art when you go to college?’”

As she grew up in central Ohio, Boehm went through “predictable waves of fascination with Greek sculpture and Rembrandt,” she says. “I was lucky enough to travel a fair amount with my parents, and I dragged them to places that they wouldn’t necessarily have gone. We went to Leiden, because I was determined to go to Rembrandt’s birthplace. And I remember very distinctly the treasury in Vienna making a big impact.”

She ended up choosing Wellesley over Smith for a couple of reasons, Boehm says, and one was its campus. “There’s nothing more beautiful than the Wellesley neo-Gothic campus, right? There was that medieval thing emerging already,” she laughs. Another was its proximity to Boston and being able to go to the Museum of Fine Arts, the Harvard museums, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

She says she struggled with deciding between history and history of art as her major. “When I was at Wellesley, art history was approached very much in a formal analysis. But I was always very interested, and again from a very early age, in the history of the church and the Reformation. So I ended up with a double major in history and history of art. And my history focus was the Reformation, especially the English Reformation. It was really only after I graduated from college that I realized I could marry these two interests if I studied the art of the Middle Ages.”

Bringing the Past to Life

While working at the Met, Boehm earned her M.A. and Ph.D. at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. She mounted shows about enamels made in Limoges betwen the 12th and 14th centuries, about the prayer book of French queen Jeanne d’Évreux, and about art made in Prague during the 14th and 15th centuries. She also co-curated a major show at the Met, titled Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven. Boehm has published extensively on subjects relating to her exhibition projects and research on the Met’s permanent collection.

‘The impulse to create works of art is, to my mind, one of the highest callings. The thing that makes works of art stand apart, in a museum context, is that they’re so public. They’re there for everybody.’

When Boehm arrived at the Cloisters, “there hadn’t been a special exhibition here since 1988,” she says. The first exhibition she curated there, in 2011, was The Game of Kings: Medieval Ivory Chessmen from the Isle of Lewis.

“The point was to make people aware that there are things about the Middle Ages that we take for granted today,” she says. “The way we play chess—that’s the heritage of the Middle Ages. The wine we drink—that’s the heritage of the Middle Ages. You need to understand that what you’re drinking now, you need to thank some monk for that. Monks, it’s not all just doom and gloom.”

Museums Matter

Boehm says that many of the objects in the Cloisters make her smile, highlighting as they do the earthy reality of their makers. Others, like the religious scenes in pages of the tiny Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, created by Jean Pucelle in the early 1300s, can bring her to tears.

“The impulse to create works of art is, to my mind, one of the highest callings,” she says. “The thing that makes works of art stand apart, in a museum context, is that they’re so public. They’re there for everybody. There are messages that the artist is sending, and there are messages that we take away, which may or may not be the same as what the artist was sending. But they’re there for everyone. You don’t actually have to be able to read. You don’t have to be able to understand complex symbolism. Sometimes people [say], ‘Oh, I’m not going to respond to medieval art because I don’t know those stories.’ But the best artists in the medieval period are also the best storytellers. And they have a way of getting to you, regardless of whether you know the particulars.”

The spring 2017 special exhibit at the Cloisters, Small Wonders, tells stories in miniature. The objects on display include boxwood beads that open to reveal intricate Biblical scenes carved in three dimensions within the space of only inches. The first object a visitor encounters is a rosary that belonged to King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, who had their own portraits incorporated into the rosary; they are shown watching a communion service. Queen Catherine apparently—and poignantly—kept the beads, which are on loan from Chatsworth House in Britain, after the couple divorced and Henry banned the use of rosaries.

Small Wonders, a Cloisters exhibit of Gothic miniature devotional objects intricately crafted from boxwood, includes: a prayer bead less than two inches in diameter depicting the nativity and the adoration of the magi, with gilded silver on its exterior; and a memento mori in the form of a tiny coffin. Both objects were made in the early 16th century in the Netherlands.

The Met Cloisters towers over northern Manhattan. An amalgam of 20th-century and medieval structures, the museum houses a remarkable treasury of art and artifacts from the Middle Ages—objects overseen by senior curator Barbara Boehm ’76.

Courtesy of the Met Cloisters

“You can see an amazing thing emerge in the Middle Ages,” says Boehm. She gestures to the capital of a pillar in one of the cloisters. “They took these capitals, these things that were just about plant life, and they start to tell you stories with them,” pointing to a carving of a biblical scene.

“You see the presentation in the temple—and I use this with kids, not assuming that they’re from a Christian background—you see an image of Joseph holding the baby, preparing to hand Jesus over to this priest. And it’s just as it is when somebody has a newborn and somebody says, ‘Can I hold the baby?’ ‘Sure, sure,’ you say. And you watch them carefully, right? You can see Joseph still holding onto the baby’s feet, like he doesn’t quite trust the priest. There are very sweet moments like that,” she says.

In addition to storytelling, original works of art of any era carry a legacy of meaning for world cultures, Boehm emphasizes. She recalls talking about this with a class she taught when she was directing the curatorial studies program organized by the Met and NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts.

“If your career is in the art world, you have to realize what a privilege that is,” she told her students. “Every day, you get to spend your time thinking about things that were made that have become a kind of global heritage, that are the highest aspirations of humankind.”

On a promontory in Fort Tryon Park in the northern reaches of Manhattan, this heritage is available to everyone. And all you have to do is hop on the M4 bus or take the A train to 190th Street.

Catherine O’Neill Grace is a senior associate editor of Wellesley magazine. Her parents took her to the Cloisters for the first time when she was 8 years old, where she acquired a lifetime passion for the Unicorn Tapestries.

To watch a video about Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures, click here.