Protest art demands a hearing. While other forms of art may unfold their meanings quietly, political posters shout their messages from atop banners and signposts.

Protest art demands a hearing. While other forms of art may unfold their meanings quietly, political posters shout their messages from atop banners and signposts. Artists use bold graphics to connect with the masses, capturing emotions and rallying supporters.

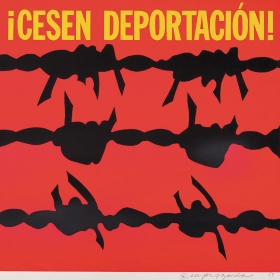

More than 25 examples of protest art are on display through June 10 at the Davis Museum, including the silkscreen print ¡Cesen Deportación! (Stop Deportation!) by Mexican-American artist Rupert García (b. 1941).

García has a long history as an activist. He served in the Vietnam War, and after returning home in 1965, he enrolled in art school at the University of California, San Francisco. As protests erupted on campuses all over the country, García realized that he could use his art to give voice to political and social causes.

He supported the Chicano movement, which, like the larger Civil Rights movement, mobilized people to demand voting rights, workers’ rights, and an end to racial discrimination, specifically for Mexican-Americans.

Among the most vulnerable groups were migrant farm workers, who had been brought from Mexico into the U.S. to work the fields of California’s Central Valley. Throughout the 20th century, Mexican workers were welcomed in times of labor shortages and then deported when they were no longer needed.

García wanted to draw attention to their plight. ¡Cesen Deportación! reflects his desire to make art that was understandable to “the folks in the neighborhood,” as he explained in 2010. The poster’s power derives from its simplicity: Three lines of black barbed wire set against a red background, with the Spanish words emblazoned in yellow across the top.

“It looks like it could have been made yesterday,” says Meredith Fluke, Kemper Curator of Academic Exhibitions and Affairs, who organized the exhibition Artists Take Action! Recent Acquisitions from the Davis. She points out that barbed wire has the capacity to divide people by shutting them out or closing them in. The imagery is easily recognizable. “The universality is what makes García’s work resonate so deeply, especially in the current political climate,” she says.

The Davis’s curators have added protest art to the collection as a way to demonstrate to students the activist thread that runs through centuries of art. Such works help to determine how people will think of political movements. “In an era where we are constantly bombarded with visual imagery, it remains important to consider the material object, and the enduring role that protest art has played in our culture,” Fluke says.

¡Cesen Deportación! (Stop Deportation!), 1973, By Rupert García, Screen print, 18 11/16 in by 25 ⅛ in

¡Cesen Deportación!; museum purchase, Marjorie Schechter Bronfman ’38 and Gerald Bronfman Endowment for works on paper, image reproduced courtesy of the artist