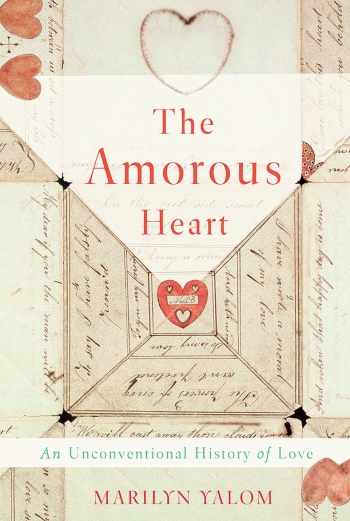

Chances are that today you—like me—clicked on a little heart icon while scrolling through your internet feeds, turning it red with meaning. The heart symbol, with its two scallops on top and V-shaped point at the bottom, has become ubiquitous, signifying concern, support, enjoyment, and yes, love. In The Amorous Heart, Marilyn Koenick Yalom ’54 traces the long history of this iconic image, delving backward in time to the medieval period, and across space to Western Europe, Asia, and the Arabic world to deliver an impressively global and richly historical overview of the human heart’s translation into sign.

After telling the story of her project’s origins in a “eureka moment” experienced while viewing a medieval brooch at the British Museum, Yalom, a senior scholar at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University, initiates a fascinating journey into the meanings of the heart via stories of ancient botany, Egyptian understandings of the soul, the rise of Freudian psychoanalysis, and the development of mass culture, among other topics. An ideograph used to express the idea of the “heart” in its metaphorical or symbolic sense, the heart symbol has not always possessed the range of interpretations it has today.

Calling the design “a pleasing form in search of meaning,” Yalom relates how the image, derived from shapes found in nature such as pears and pinecones, moved beyond being a pure decorative embellishment to acquire the complex connotation of emotional love, the meaning of which has evolved over time.

The Amorous Heart is full of references to a rich range of literature, opera, art, and everyday objects that together form an enlightening read. First found as an illustration of love during the medieval period, the heart icon expanded in significance during the 16th and 17th centuries to acquire a range of psychological meanings and to represent a variety of emotions jostling with each other. Subsequently, the design was understood at various times to be more or less chaste, amorous, political, independent, romantic, and commercialized, illustrating how, as Yalom poetically puts it, “symbols have a way of slipping out of their envelopes and assuming meanings and uses that were never anticipated.”

In turning from past to present, Yalom notes that digital life has transformed “heart” into a verb, democratically offering the icon to everyone. Emphasizing that “when words fail us, we fall back on signs,” she unfolds how the heart has increasingly come to speak without words for us in times both full of joy and marked by grief.

Hinrichsen, associate professor of English at the University of Arkansas, is president of the Society for the Study of Southern Literature. She is a co-editor of Small-Screen Souths: Region, Identity, and the Cultural Politics of Television (LSU Press).

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.