When most people learn about bacteria or fungi around them, they grab the cleaning spray. Anne Madden ’06 grabs a petri dish and hopes to discover a new species, a novel antibiotic, or even a way to brew a better beer.

When most people learn about bacteria or fungi around them, they grab the cleaning spray. Anne Madden ’06 grabs a petri dish and hopes to discover a new species, a novel antibiotic, or even a way to brew a better beer.

Anne Madden ’06 found her calling as a research scientist standing in a “cathedral of plants” in the jungle at La Selva Biological Station in northeastern Costa Rica.

At the end of her junior year at Wellesley, a friend from Madden’s plant biology course told her that a space had opened up for a fellowship in Costa Rica. Madden spoke to her professors about it, excited, but when she learned that her friend Katie Moseley ’06 was also interested, she told the professors that they should really choose Moseley, since she was a Spanish and biology double major. Meanwhile, Moseley was arguing in favor of Madden. Wellesley found funding to send them both.

It was a magical experience. Madden describes learning to identify the duck-like call of a tree frog no bigger than a fingernail, and catching snakes with herpetologists. Primarily, though, she and Moseley were there to study the way that light filtering through the canopy affects plant growth. “As soon as you get off of any path, you’re in the dark. … That’s something that we never realized, that we would spend an entire summer in Costa Rica and come back pastier than when we left,” Madden remembers.

But more than anything, what stuck with Madden was the feeling she got working with scientists who were so passionate about their research and making new discoveries. “I really did love how scientists in the jungle—and scientists in general—when they start talking about what they’re doing research on, they just glow,” she says.

Madden has been chasing that feeling ever since, which over the years has led her to studying microbes in Paintshop Pond back on campus, sniffing dirt to find novel antibiotics for a biopharma company, hanging from barn rafters to collect wasps (and the bacteria on them), hunting for yeast on wasps in a Massachusetts vineyard to brew a tastier beer, and speaking on the TED Conference main stage in Vancouver, B.C.

Today, Madden’s work straddles industry, academia, and the public sphere as she discovers new microbes and puts them to work for humans. She is a partner at Raleigh, N.C.-based Lachancea, which sells novel yeasts that Madden helped discover to breweries. Until recently, she was director of scientific communication at Boston-based Indigo Agriculture, an agriculture technology company that uses plant microbes to improve crop yields. She is developing an interactive exhibit with artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya to introduce audiences to microbes. She has a busy social media life (@AnneAMadden on Twitter and Instagram), spreading her enthusiasm about microbes through photos and fun facts (with cameos from her kitten, Puffin). Oh, and she continues to publish research papers.

With microbes, the jungle is everywhere—and so is Madden.

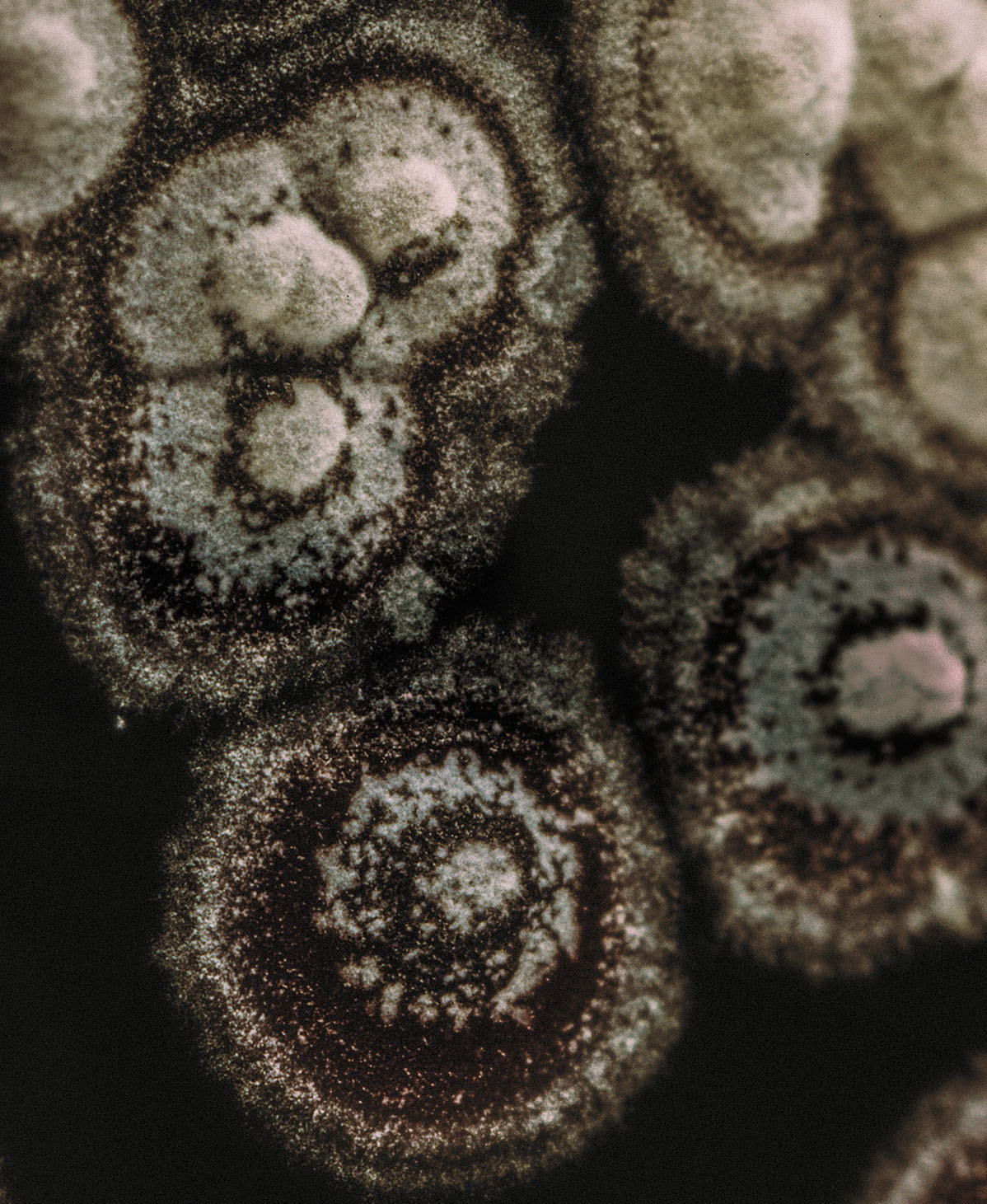

Microscopic photography of Streptomyces coelicolor on silk textile.

A Budding Biologist

Madden has been interested in science ever since she was a child growing up in Maine. She suffered from severe depression and anxiety, which resulted in her being out of school for several years. “A lot of things were confusing, and there wasn’t a lot of rationality to when medications would work or would not work. And my parents were going through a divorce,” she says. With help from doctors and a changing physiology, she says, she was able to return to high school.

She remembers a particular moment her sophomore year, when her anatomy class dissected a cat. “I saw that this beautiful elegance of all of our movement, which seems so complex and beautiful and dynamic, is made possible by a very simple system of bones that don’t move and muscles that pull them together. And from that emerges things that seem complicated and somewhat magical. [T]hat’s my one moment of seeing that science offered an opportunity to provide predictability, if you could just find out more, and that there was more beauty and more wonder in the world, the more I learned,” she says.

At Wellesley, after her summer in Costa Rica, Madden began working in the lab of microbiologist Mary Allen, then Jean Glasscock Professor of Biological Sciences, assessing whether microbes from Paintshop Pond had antibiotic resistance because of their exposure to higher than normal levels of toxic compounds. “That was my pathway to microbiology, understanding that there are discoveries, adventures around us with microscopic life,” she says.

After graduation, Madden took a job in industry, working for NovoBiotic Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Mass. Because the company’s mission is to develop antibiotics, she got to work with “fun microbes” like the bacteria that caused the plague, and antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” like MRSA and VRE. “My job was to try to get [the pathogen] to grow in the morning,” Madden says “and then try to kill it with something that another microbe had produced in the night.”

Where’s the best place to find new antibiotics? Turns out, dirt. “It’s where you’re going to find an incredible amount of diverse microbes. So … if you want to screen a bunch of different [microbes], you can find them in the soil. Historically, most of our commercial antibiotics come from a certain group of bacteria, and those are often found in the soil,” she says.

Madden and her colleagues were constantly armed with baggies in case they came across literal pay dirt in their backyards or while they were on vacation. “There was a lot of time spent sniffing dirt, because the smell that we associate with really great, fresh-turned earth is a compound called geosmin that’s also produced by the bacteria that frequently [produce antibiotics],” says Madden.

This introduction to industry made Madden appreciate not only how many microbes there are in the world, but what each microbe can do—for themselves, and for humans. “[Microbes] oftentimes look the same: balls or rods. But they diversified in terms of their chemical abilities, their ability to transform nature. … And those chemicals are basically everything you can imagine—flavors, aromas, medicines, therapeutics, enzymes that help us break down stains on our clothing. I mean, just anything, a microbe has found a way to do it, because we have that many species diversifying over that many years,” Madden says.

Just how many species are we talking about? “If you had a sugar packet worth of soil, it’s going to have double the number of species that we have in all of the zoos in all of the world,” she says.

Welcome to the jungle.

Beer (and Wasp) Nerd

When Madden applied to graduate school, she looked for a place that had the interdisciplinary, liberal arts feel she loved at Wellesley. She also was interested in studying how organisms interacted with each other. That led her to the lab of behavioral ecologist Philip Starks at Tufts, where she studied the microbes that live on wasps. “Nobody knew anything about the microbes associated with wasps at that time. So it was great. They live on all of our windows. We know nothing about them. There’s got to be an interesting story there,” she says.

Madden studied the microbes associated with a native Massachusetts paper wasp and an invasive paper wasp from Europe. “[The wasps are] very closely related. They have very similar behaviors. But we don’t know if they host different microbial communities. Why that could be relevant is if those wasps are moving certain microorganisms around as they travel from vineyards to other food sources,” she says. Along the way, Madden found that the invasive wasps had microbes associated with grape sour rot disease, which can devastate vineyards.

Madden’s job involved collecting wasps in the wild. She would visit orchards and people’s houses and once even advertised for “free wasp removal” on Craigslist. Often, she needed to collect the wasps live on their nests. “So I would frequently be poised, hooked on rafters of old barns, with really long tweezers that were sterilized, trying to put the wasps into plastic bags in the middle of the night, [when] they’re less active,” she says.

‘I would argue society should just be like jumping up and down, bouncy house fashion, when a microorganism species is discovered.’

In the process, Madden discovered a world of microorganisms that live inside wasp nests—including a new fungus species that she found in a paper-wasp nest above a dumpster at Tufts. The fact that you can dumpster dive for an undiscovered microorganism thrills Madden. “I will say that my friends [who] discover new dinosaur species get a lot of media attention for their dinosaurs—and I love dinosaurs. But when you discover a new microbial species, you get a living creature that you don’t know what it can yet do. … That means it has the potential to create new things. And so, I would argue society should just be like jumping up and down, bouncy house fashion, when a microorganism species is discovered,” she says.

After Madden got her Ph.D., she received an Alfred P. Sloan Microbiology of the Built Environment Postdoctoral Fellowship, during which she was co-advised by Noah Fierer at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and Rob Dunn at North Carolina State University. Much of her research was focused on the microbes and bugs that are our roommates (and bodymates), often unbeknownst to us. Among other things, she helped create an “atlas” of arthropods (dust mites, spiders, cockroaches, and much more) that live in our homes by sequencing DNA from dust samples from more than 700 homes in the continental U.S.

Working with Dunn in particular meant that she collaborated on many different projects. One day, he emailed her about a project that he and a professor of brewing sciences had cooked up for the next year’s World Beer Festival in Raleigh, N.C. “[They] had decided to do an education outreach project where they would team up, find a wild yeast from someplace, and make a beer to highlight that microbes can do all sorts of human applications. … I offered to help because I work on wasps, and it’s becoming clear that wasps play a role in the natural ecology of yeasts,” Madden says.

Today, just about every beer in the world is made from one of two species of yeast—ale yeast or lager yeast. “Now, there are lots of subspecies in there, so there’s variability, but still one or two, and if you’re like, ‘I’m a real beer geek nerd,’ and I say that as one, maybe there’s a third. But really, that’s the traditional limit,” she says. Madden went to the outer limits, looking to wasps to find likely candidates. Yeast feeds on sugar in flower nectar and fruit. And when wasps sip on the nectar, some yeast hitch a ride. Some of these yeast are capable of making alcohol.

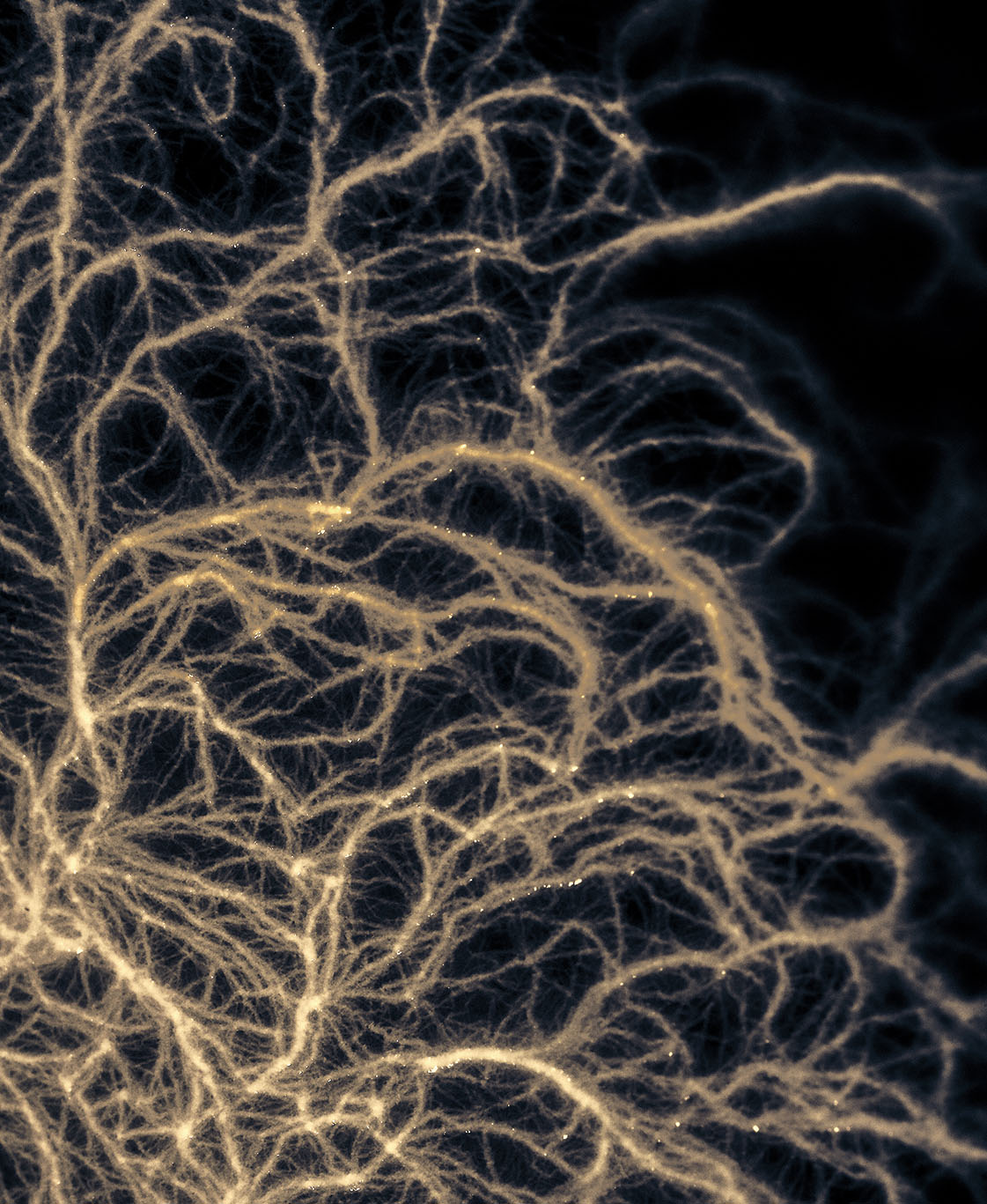

Microscopic photography of Bacillus mycoides.

Madden started scouring houses, orchards, and vineyards for wasps—she decided to get 30 insects and choose a yeast from each. “And there’s a German Shepherd that’s chasing me that’s eating the wasps, and these are not the things that I expected to be hurdles for doing research,” Madden remembers, laughing. After she caught the wasps, she developed a process to grow their hitchhiking microbes and then select yeasts that had characteristics she was interested in. Those characteristics included that they were food safe; could ferment maltose, the major sugar in grains; and even that they produced fruity and floral aromas when growing on petri dishes.

Ultimately, Madden sent two yeasts off to a brewery, not that optimistic, and the brewery picked one to brew a beer. About three weeks later, her colleague at NCSU, John Sheppard, got a sample from the brewery, and shot off an email to Madden in which he described it as “shockingly palatable.” Today, Sheppard and Madden run Lachancea LLC, named after that fateful strain of yeast that Madden caught on a wasp from a vineyard in Massachusetts. Beers brewed from yeast licensed by their company have won awards, like Nickelpoint Brewing’s Raspberry Wild Siren Sour Ale.

Rob Dunn at North Carolina State says that what at first looked like enormous good luck in finding good brewing yeast was, in fact, the result of the unique skill set that Madden brought to the task. Her experience in industry, for one, and her ability “to think like a microbe … what they might be doing.” Also, he says, “Anne has a super uncanny nose for sniffing out unusual microbial ongoings”—her nose always knows whether what’s growing on the petri dish is useful or not. Finally, Dunn says, “Anne also has a sense of wonder about the microbial world that’s very genuine.”

This sense of wonder comes through, and is infectious, when Madden talks about her research. She has always recognized the importance of communicating about her work. Still, she was surprised to hear from the TED Conference. “I got an email out of the blue, and I read it and I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh. I’m being invited to attend TED. I can’t believe it. Do you know how hard it is to get to be able to attend?’” But then she reread it and realized she was being invited to give a TED talk. “I read it I think six times, and I thought, ‘Oh. It’s so much better-slash-worse.’” Her talk, “Meet the microscopic life in your home—and on your face,” delivered on the main stage in Vancouver, B.C., in April 2017, argues that microbes are the best source of new technology on the planet.

It’s an argument she has continued to make today as a science communicator, most recently for Indigo Ag; in a collaboration with a New York artist to make a pop-up educational exhibit about microbes; and in her daily Tweets and Instagram posts. She also keeps a hand in academic work, publishing papers on research she did with collaborators at Tufts, NCSU, and elsewhere. “I like straddling the two spaces [industry and academia],” she says.

Wherever Madden’s career takes her, adventures and discoveries are waiting, literally all around her. Because with microbes, as she says, “you don’t need a jungle to find them.”

Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’99 is a senior associate editor at Wellesley magazine.