The popular course ENG/HIST 221: The Renaissance interrogates the idea of the thing that historians and literary scholars have called the Renaissance.

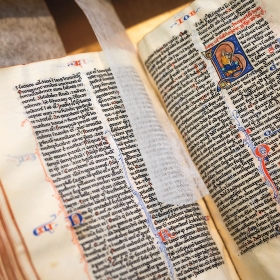

Historiated initial of King David from a 14th c. Bible made in Paris. Manuscript on fine vellum, gothic script.

Students taking ENG/HIST 221: The Renaissance with Sarah Wall-Randell ’97, professor of English, and Simon Grote, associate professor of history, likely arrive at the first class with some basic knowledge of the course’s subject. That era, roughly described as between 1300 and 1600 in Europe, has long captured the imaginations of scholars and the general public alike.

One reason, says Wall-Randell, is the pervasive idea that it’s possible to “trace the birth of all of the complicated, contradictory, atomized ways of being a human in the present to a genealogy that starts with the Renaissance.” Grote, who is director of Wellesley’s Medieval and Renaissance Studies Program, says that similarly, many historians have defined the Renaissance in terms of important developments such as the emergence of modern political theories and institutions. But Wall-Randell and Grote critically examine those ideas in the class.

“We joke that we draw students into the course with the promise that they’re going to learn all about the Renaissance, and then when they get there, we say, ‘So … is the Renaissance a real thing?’” Wall-Randell says. “The point of the course is to interrogate the idea of the thing that historians and literary scholars have called the Renaissance. … Who is it for? When did it start? Is the Renaissance over?”

Sarah Wall-Randell ’97, professor of English, and Simon Grote, associate professor of history, with their class on a visit to Special Collections, temporarily based in the Davis Museum.

The consistently over-subscribed course, which they taught for the fourth time this semester, is structured in the “great books” format, an approach Grote enjoyed when he taught at Princeton as a postdoc in its Society of Fellows. Every week in Grote and Wall-Randell’s course, students read a book of interest to scholars who work on the question of what the Renaissance was, from Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince to Moderata Fonte’s The Worth of Women: Wherein Is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men.

For each book, one of the professors delivers the main lecture, with background and historical context for their reading, and the other delivers a counterpoint. “Each time, [students are] getting two different sets of questions about the text,” Grote says, as well as insight into different disciplinary techniques. While Wall-Randell focuses on close readings of the text, Grote often asks, “What did the author—plus other people involved in making a text—want to happen as a result of making a text public, having a text read? What did authors want readers to do with the text?”

Wall-Randell and Grote spend two class periods with Ruth R. Rogers in Special Collections exploring examples of texts made during the Renaissance. “They read about the invention of movable type, and they see books that illustrate that history, and then analyze them themselves in the same session,” Grote says. The experience gives students a “little taste of what it could mean to do research with old books,” Wall-Randell says.

“The point of the course is to interrogate the idea of the thing that historians and literary scholars have called the Renaissance.”

—Sarah Wall-Randell ’97, professor of English

One of the books the students see is a manuscript of two Giovanni Boccaccio texts, written in Italy in 1430. “Touching this book is like holding hands with history,” Rogers, curator of Special Collections, told the class as she showed them its colophon, the place in the book where the scribe often provides a date, place, and sometimes their name. “This manuscript has a boldly written colophon, where the scribe proudly proclaims in Latin, ‘Thanks be to God, Amen. 1430. I, Karolus de Battifolle, wrote this book by my own hand, in my youth,’” Rogers says. “The reason it is so touching is that he was learning to be a scribe, and the script and decoration is messy in a lovely rustic way.”

“We want to cherish and celebrate material things,” Wall-Randell says. In that spirit, as an assignment the professors gave each student a hardcover blank notebook to create their own commonplace book of quotations from their readings.

Grote adds that they will return the commonplace books to the students before they leave for the summer, in the hope that they’ll continue to refer to them. Perhaps there might be “observations that an author makes that really get you thinking about certain things, and that you want to take with you in your memory long after the course ends,” he says.

[substory:1]