As the world grapples with the challenges of moving on from fossil fuels, Professor of Environmental Studies Jay Turner and his students are monitoring efforts to create a clean energy grid.

At the end of 2023, a new electric power system quietly came online in Hawai‘i. Unlike its predecessors, this system doesn’t run on coal, natural gas, or fossil fuels of any kind. The Kapolei...

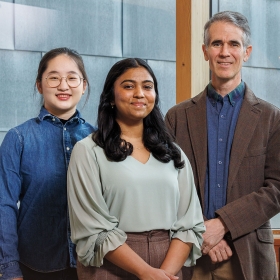

Jay Turner (center) and some of the student researchers who have helped him track the EV supply chain (from left): Xiner Chen ’26, Pranathi Chintalapudi ’25, Nadia Vu ’27, and Rena Ramaraju ’25.

At the end of 2023, a new electric power system quietly came online in Hawai‘i. Unlike its predecessors, this system doesn’t run on coal, natural gas, or fossil fuels of any kind. The Kapolei Energy Storage facility in Oahu is, essentially, a big battery enabling the state’s renewable energy to be distributed, used, and most importantly, stored. And its creation, setbacks and all, captures some of the largest issues surrounding the transition from fossil fuel-based energy sources to renewable or “clean” energy.

Of the many challenges facing the global community because of climate change, one of the most significant is the need to transition to clean energy. And electricity is at the heart of this: It powers homes, workplaces, and increasingly, cars. A multitude of plans, large and small, are in the works to make this shift, with goals ranging from the College’s own push to be carbon-neutral by 2040 to Hawai‘i’s commitment to no longer burn fossil fuels for electricity by 2045.

“Lithium ion batteries are doing the heavy lifting in this clean energy transition,” says Jay Turner, professor of environmental studies at Wellesley. “We’ve seen them over the last decade go from powering our laptops to powering cars, and now they’re powering entire electric grids. … And we’re going to see more of that.”

One reason more projects like the one in Hawai‘i are coming online is the billions of dollars of investment in clean energy in the U.S. that were unleashed by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. Turner and his student researchers at Wellesley had been tracking the progress in the electric vehicle (EV) supply chain since before the IRA, but their work became even more critical after a wave of new projects followed passage of the legislation. The database they created has evolved into a dashboard, the Big Green Machine (the-big-green-machine.com), detailing how much is being spent and where, tracking the production of electric vehicles and battery cells, and more. Their project has garnered the attention of the clean-energy community—and the White House. And it just keeps growing.

*Batteries not included

In 2010, when Turner started studying batteries, the world, and batteries, were in a much different place. Electric cars were more of an idea than a reality, although hybrid gas/electric cars like the Toyota Prius were gaining traction. Tesla Motors had begun production of its first electric car in 2008, but with a price tag of more than $100,000, it was out of reach for the average consumer. The need for innovation increased as the realities of climate change grew more stark.

Turner’s work studying batteries “really came out of the classroom. I am trained as a historian, but I teach an interdisciplinary introductory course on climate change,” he says. The need to curtail and eventually eliminate dependence on fossil fuels was obvious, but the solution was not so obvious. “Everybody knew batteries had to play some role in this, but they were literally a black box—and kind of figuratively a black box. Neither I nor my students really knew how to think about batteries, where they came from, what role they were going to play. So, that was the starting point for this project over a decade ago.”

The work ultimately grew into Turner’s 2022 book, Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future. (The book was the recipient of the Susanne M. Glasscock Humanities Book Prize, a finalist for the Cundill History Prize, and a gold medal recipient of a Nautilus Book Award in the sustainability category.) In it, Turner goes into the history and development of the batteries we’re familiar with today—from the little ones thrown in remotes and children’s toys to the larger, more complex batteries that power laptops and cars—and delves into the issues involved in the large-scale production of batteries necessary for a clean energy transition. Making batteries that can power cars (and the energy grid) at the scale needed to address climate change will require a massive ramp-up in infrastructure, from mining the necessary minerals to creating battery-production plants.

“The book ends with a call for domestic policy to support investments in the clean energy supply chain and specifically in batteries,” Turner says.

Jay Turner

Tracking the supply chain

With his book off to the publisher in the spring of 2022, Turner was thinking he’d have a quiet summer, but the world had other plans. That semester, Turner had Arzy Abliadzhyieva ’25, a Ukrainian student, in two of his classes. As the war in Ukraine escalated, it became clear that Abliadzhyieva needed to stay on campus over the summer, so with help from Cathy Summa ’83, associate provost and director of the Science Center, and her colleagues, Turner found funding and hired Abliadzhyieva as a research assistant for a summer project.

At the time, he didn’t really have a clear sense of what that project was going to be. “I remember talking with Arzy, saying, ‘All of a sudden there is a lot of activity in the supply chain around batteries and electric vehicles, and I’m starting to just be overwhelmed by the press releases, the media announcements, and the news stories,’” he says. “‘Maybe we should start tracking this.’”

They decided to create a database of all the domestic sites related to electric vehicle batteries. “It was a lot of exploration and figuring out what sources we wanted to use, how we wanted to manage and collect information, how to store it, what to do with it,” Abliadzhyieva says. “There was a lot of trial and error, and with the help of Professor Turner, I was able to begin collecting this information, and later, more students joined.”

As Abliadzhyieva was collecting data that summer on publicly announced projects, including investment amounts, target production, and employment levels on the EV supply chain, the work became even more relevant. On Aug. 16, 2022, just a few weeks after Turner’s book was published, President Joe Biden signed the IRA, which includes several critical provisions to spur investment in clean energy and manufacturing and to strengthen domestic supply chains, all while lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

“When the Inflation Reduction Act passed, it had specific provisions that required that materials be sourced from free-trade partners, or assembled in North America, or not include China. And suddenly, these questions of the supply chain had new relevance,” Turner says.

“When the policy was passed, there was so much more attention,” Abliadzhyieva says. There was more media interest in the work they were doing, and more projects being announced every day, from plants refining lithium to factories making electric vehicle fast-chargers. Turner extended what was initially a summer project into the school year, with the support of a Wellesley Brachman Hoffman Small Grant and the Knapp Social Science Center, and brought on another student research assistant, Pranathi Chintalapudi ’25. He also began posting regular updates on Twitter (now X) with their data, and his post with the six-month post-IRA data “went, in the clean energy world, a little bit viral,” he says. “A couple of weeks later, I came back to my office after teaching class, and there was an email from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.”

Click here to download a PDF of the graphic above

Getting the attention of policymakers

“There’s been so much interest in this project and the work that we’ve done that it’s kind of gone past just the book and taken on a life of its own,” Turner says. The email from the Office of Science and Technology Policy asked if Turner would be interested in coming to Washington, D.C., with his students to brief the chief data officer of the United States and other members of the office on his work. The answer was, of course, yes. So, in March 2023, Abliadzhyieva and Chintalapudi accompanied Turner to the White House—well, technically, the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building, the ornate 19th-century building that houses staff next door to the White House.

The administration wasn’t interested only in what Turner’s research could offer them, but also in how they could help his project as well. “They were curious to know what other federal resources, like datasets and information that they were collecting, might be helpful to us,” he says. “They had datasets we were not using around social indicators that we’ve integrated into our analysis since.”

In addition to furthering their research, the trip was a huge honor for the team—and a big surprise to the student researchers. “[We] were just very scared, to be honest,” Chintalapudi says. “We were wondering, why do we have a seat at the table? We were sophomores at the time, and it was our first research experience. But Professor Turner played a huge role in making it feel like we were co-creating a project with him, and he really encouraged us to step up and be major presenters in it. So, it was a very, very unique opportunity and a remarkable experience.”

Chintalapudi was particularly impressed that the meeting wasn’t a straightforward presentation, but rather a roundtable discussion. “It was super exciting to be able to have a seat at the table where our data was being used to discuss and shape policy,” she says. Abliadzhyieva agrees. “It just felt really empowering to be in that place and see how science makes its way to decision-making spaces,” she says.

And the White House wasn’t the only entity taking note of their work: “Our data has been cited in the New York Times, the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, the MIT Technology Review, and Canary Media. It’s gotten a lot of attention,” Turner says.

At the time of this writing, the latest update Turner and his students posted was on March 16 and showed that in the 582 days since the IRA passed, there were 96 newly announced projects in the EV supply chain, 54,739 newly created jobs, and $85 billion in newly announced investments. As they’ve analyzed the data, they’ve found that investment in this area is happening at three times the rate it did before the IRA passed. If all these projects come to fruition, Turner and his students estimate that by 2030, 5.2 million EVs could be manufactured each year. (In 2023, 1.2 million EVs were sold in the U.S.) They are also tracking where these investments are being made, down to the congressional district. More than 90% of the projects are located in Republican-led districts—a notable fact during an election year.

“There’s a lot of work left to be done on this clean energy tracking,” Turner says. “I think there’s a lot to be learned about the kind of commitments that have been made to building out the clean energy supply chain. But also, how many of those actually get built? What’s the relationship between commitment and follow-through?”

“We were wondering, why do we have a seat at the table? It was our first research experience. But Professor Turner played a huge role in making it feel like we were co-creating a project with him.”

—Pranathi Chintalapudi ’25

What lies ahead

Although the work continues, the focus and student researchers are shifting a bit. Abliadzhyieva, a media arts and sciences major, is studying abroad in London this semester, and Chintalapudi, an economics major, is now working with an MIT professor researching accountability and misinformation. More students joined the project last fall, including Xiner Chen ’26.

Despite these changes, the collaborative environment Turner creates with his students remains constant. “The students are my sounding board,” Turner says. And they act as sounding boards for each other, as well. “We are a very small group currently, and we are able to discuss what our thinking is,” Chen says. “For example, we’re discussing environmental justice metrics and how we could implement those in our database. It’s a very free discussion base, and Professor Turner is very supportive of us.”

And while this is ultimately Turner’s project, students are getting firsthand experience in research that isn’t often available to undergraduates. “The students who are working with me, they’re doing a lot of the nitty-gritty tracking work,” Turner says. “They’re taking the first pass at reviewing that information, comparing it against what’s in the database, and then making updates. Students who are doing this are, on the one hand, just learning a lot about the mechanics of sourcing and manufacturing clean energy technologies. But they’re also learning about the relevant policies and laws, like the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.”

As an environmental studies major, an economics minor, and an international student, Chen is particularly interested in how U.S. policy is shaping economic development related to investments in clean energy. She is also excited to be working on something that has larger implications. “I feel like our work is useful and positive,” she says, particularly because of its transparency and availability to the public.

Chintalapudi agrees: “It is this issue of major global importance. And I think the way we reflected that in how we approached the research was through public awareness. We used public sources. We made monthly public reports, and our database was translated onto the first publicly accessible dashboard. And I think that’s a huge component of tackling global issues that we really emphasize through our work.” Turner still regularly updates his findings on X, and the EV Supply Chain Dashboard is available on the Charged website: charged-the-book.com.

Not only will Turner and his students continue the work they’ve already begun, but the work itself continues to expand to incorporate more data and fields. After starting out focusing on the United States, it expanded to North America; and after an initial focus on batteries and EVs, Turner is expanding the project to incorporate the tracking of solar and wind investments. “I’m excited to launch our tracking of the wind and solar industries,” he says. A new dedicated website for the expanded scope went live this spring at the-big-green-machine.com.

“There’s a lot to be learned about big policies, big laws like this. We need big policies and big laws to help address climate change,” Turner says. “But there are a lot of questions that emerge. Where are the investments going? Are we actually investing in resource extraction, which has lots of costs for local communities and the environment? Or are we just investing in factories, which are creating jobs and are generally welcomed by communities?”

Turner is quick to point out that many of these mines and factories haven’t been built yet, making this a critical point in the transition to clean energy. “There’s a chance to ensure that those supply chains are built in ways that are more just and more sustainable,” he says. “We need economists and computer scientists and studio artists. We need all of these people thinking about this, engaging, and taking action.

“And this is the moment to do that work.”

Jennifer E. Garrett ’98 is a writer and editor living in the Boston area.