Assistant Professor of Art Nikki Greene likes to think outside the classroom. Art History 316, The Body: Race and Gender in Modern and Contemporary Art, is held in a small seminar room, but it’s possible for anyone in the world to listen in by searching for #ARTH316 on Twitter.

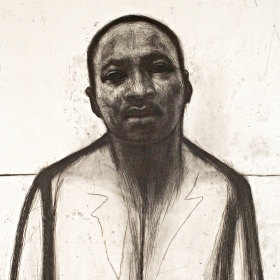

Photo by Richard Howard

Assistant Professor of Art Nikki Greene likes to think outside the classroom. Art History 316, The Body: Race and Gender in Modern and Contemporary Art, is held in a small, dimly lit seminar room in Jewett overlooking Severance Green, but it’s possible for anyone in the world to listen in on the discussions that happen there by searching for #ARTH316 on Twitter.

Before a class that included discussion of Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s essay “Going Native: Paul Gaugin and the Invention of Primitivist Modernism” and Adrian Piper’s “The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists,” students tweeted incisive and potent reactions to the readings. One student tweeted: “Primitivism is a gendered, colonial discourse. Gaugin’s art consumes the brown female body and spits out the bones.” Another commented, “Why should WOC artists have to embrace the postmodern moment when Western modernism operated on their invisibility? #AdrianPiper”

Greene requires that everyone in ARTH 316 tweet a summary or cogent point about the week’s readings. “Twitter really forces you to get to the point. What are the crucial elements of this article? … I’m amazed at what they can come up with,” she says. Greene also likes that by taking the conversation online, students can break beyond the confines of Wellesley.

When you’re teaching a course on race and gender, the outside world also has a way of coming into the classroom. “The challenge is that there are always new incidents where we have to think about race more critically,” Greene says.

When Greene first taught the course in 2012, the class discussed Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old who was fatally shot by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer, in February 2012. “[At the time,] we were talking about Trayvon Martin, and what his image meant, and the repetition of the image of him in the hoodie,” she says. Now, four years later, that image is still echoing through American culture. She points to Claudia Rankine’s 2014 meditation on racism, Citizen: An American Lyric, which is a reading in this year’s class. The cover of Citizen is actually a photo of an unsettling 1993 piece of artwork by David Hammons, In the Hood, which consists of a hood cut from a sweatshirt and hung on a wall.

‘There continues to be such a great need to provide students a critical lens for what they’re seeing.’

The piece was made more than 10 years ago, yet today, it immediately calls to mind Trayvon Martin’s death. “The idea of the threat of the black male has been present for a long time. So when we get to [In the Hood], we’re going to talk about lynching first … and think about this as more than just a contemporary issue, but historically speaking.”

Greene hopes that her classes allow students to better understand how to deal with images generally. “There continues to be such a great need to provide students a critical lens for what they’re seeing,” she says.

Her other great hope is that her classes make her students feel that “they have a place in the art world, that they don’t have to be intimidated by going into a museum,” she says. Greene tells a story about taking her students in ARTH 258, The Global Americas, 1400 to Today, to Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The curator, Dennis Carr, spent an hour and a half with the class, talking about the profound influence of Asia on the arts of the colonial Americas. Afterward, she asked one of her students, a Latina woman, what she thought about the show. The student gushed about the experience and “She said something to the effect of, ‘I never felt like the museum was a place that I could be, or that I would enjoy,’” Greene says, and now she loves museums. “Mission accomplished.”