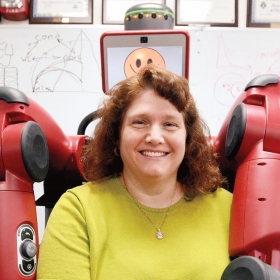

Holly Yanco ’91

Holly Yanco ’91 runs a “10,000-square-foot robot skate park.”

Courtesy of University Of Massachusetts Lowell

Holly Yanco ’91 is a professor of computer science at UMass Lowell and director of the New England Robotics Validation and Experimentation (NERVE) Center, or, as she calls it, “my 10,000-square-foot robot skate park.”

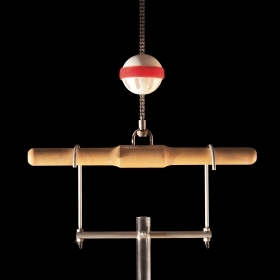

The NERVE Center is the only comprehensive indoor site for robot experimentation and validation in New England. In short, Holly says, robots are “put through their paces.” The facility includes different terrains and obstacles for robots to navigate, like cobblestone, brick, sand, rock walls, doors, splash pools, and even a rain simulator. Robotics researchers from other universities, area companies, and even the U.S. Army come to the NERVE Center to put their robots to the test and train operators.

One example is Quebec-based B-Temia, which makes robotic exoskeletons for people with mobility issues and for soldiers. Such devices might help people walk farther, or carry heavier loads. As part of her work with B-Temia, Holly is collaborating with physical therapists at UMass Dartmouth. “As we start to look at how we could evaluate the exoskeletons and use them, obviously I don’t have a nursing or [physical therapy] background, so that’s why we’re starting to involve folks in that department,” she says. “One thing about computer science is it allows us to be really interdisciplinary.”

Holly also runs the Robotics Lab at UMass Lowell, which she founded in 2001. Her main research interest is human-robot interaction, which she defines very broadly. “It’s not just designing interfaces or looking at methods to use robots. It’s also, how do you design autonomy for the robots so they can do what they do best, and let people do what they do best, and work together?”

A corollary of this question is, how do you foster the appropriate amount of trust in a robot? It’s not a good idea for people to blindly trust robots at all costs, Holly says. “You want them to trust [the robot] to the amount that it can be trusted, right? Because if they trust it too much, then you’re going to have problems, because the people are going to think it’s going to be able to do something that it can’t. But if they trust it too little, then they don’t let it do the things that it can do well,” she explains. Holly has collaborated with researchers at Carnegie-Mellon to create design guidelines to ensure that operators trust their robot the appropriate amount.

Although she works at a large research university now, she is very glad to have gone to a small liberal-arts school as an undergrad. “I was glad to have had the foundations at Wellesley, where you had that smaller class experience,” she says. In grad school at MIT, she’d notice that when she’d wait after class to ask a professor a question, “A male student would come up, and the teacher would look at the male first. … [But] we don’t take any flack, having been at Wellesley. [President] Nan [Overholser Keohane ’61] always said, ‘Not equal opportunity, but every opportunity.’ I think that was part of it,” Holly says.

In addition to her research and teaching at UMass Lowell, Holly runs several outreach programs to help attract students from kindergarten through college to computer science. Artbotics, a collaboration between UMass Lowell’s computer science and art departments and the Revolving Museum in Lowell, introduces students to CS by creating interactive public exhibits. “I always joke, it’s the cheese sauce on the broccoli,” Holly says. Botfest, an all-ages robot science festival at UMass Lowell, attracts about 4,500 people each year. Botball is a team-based competition for middle- and high-school students.

Holly’s introduction to computer science was in industry—as a high-school student in Northborough, Mass., she did a summer CS program at Digital—but she’s very happy she wound up in academia. “It feels like you’re in a startup, to some extent, but without the risk involved. … I get to try a lot of different things this way,” she says.