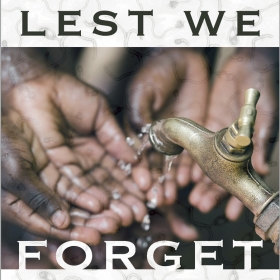

Lest We Forget chronicles the time Kwan Kew Lai ’74 spent working as a doctor during the Ebola crisis in Liberia and Sierra Leone, offering an important perspective for understanding that crisis.

Kwan Kew Lai ’74

Lest We Forget: A Doctor’s Experience With Life and Death

During the Ebola Outbreak

Viva Editions

240 pages, $11.99

Lest We Forget chronicles the time Kwan Kew Lai ’74 spent working as a doctor during the Ebola crisis in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The book offers an important perspective for understanding that crisis and the tremendous losses that it caused. It’s also a riveting read.

At the time of her first Ebola assignment with International Medical Corps, Lai, who received Wellesley’s Alumnae Achievement Award in 2017, already had extensive experience working in challenging, low-resource settings as an infectious-disease specialist. Ebola, however, proved to be a singular and formidable challenge.

Having watched the Ebola crisis unfold from the safety of the United States, I was inspired by the bravery of those who volunteered to directly combat this deadly disease, and was very curious as to the logistics of providing this care safely. Lai’s memoir provides many interesting details, such as how the wards are structured—patients presenting with symptoms are first triaged, and their specific symptoms (fever, pain, diarrhea, bleeding) are assessed for likelihood of Ebola, as well as whether they had any contact with an Ebola sufferer. Those of concern for Ebola are placed in a suspected ward; three negative tests rule out the disease. Those who test positive are moved to the confirmed ward, where suffering is unimaginable. Just over half of patients eventually make it out alive.

Lai learns the intricacies of caring for these patients, including the meticulous donning and doffing procedures for protective gear, which take 20 minutes at a time. She also bumps up against the limits of her ability to provide both care and empathy; the heat and humidity make it impossible to wear the protective gear for very long, so patients must be attended quickly. In addition, health-care providers’ entire bodies are covered by gear except their eyes, making an already horrific experience for patients further dehumanizing. But there is no safe alternative. Patients who enter the wards can no longer see their own uninfected loved ones and are starved of human touch, even small children and infants whose mothers are either dead or not sick. Most of those children will not survive. Of all of the heartbreak this book portrays, this may be the deepest cut.

The first part of the book takes place in Liberia. Lai recounts each day in chronological order; this can be disorienting as she cares for multiple patients at a time, and it can be hard to keep track of them while reading. However, it has the benefit of depicting exactly what an Ebola day looks like—the chaos, the fear, the difficult decision-making, and the multiple, simultaneous challenges faced by the care teams.

In depicting her second experience, in Sierra Leone, Lai shifts to the stories of individual patients or families over time, so that the reader is able to better understand the trajectory of disease from the patient perspective. The change in structure is effective, providing a more thorough view than either style would have alone. Lai’s own thoughts and feelings, interspersed throughout the narrative, are an essential aspect of telling such a resonant story.

The reality of the Ebola epidemic can be painful to read about, because it contains so much tragedy. As an experienced doctor, Lai maintains sufficient distance in order to make the experience tolerable for the reader, while still exhibiting empathy and not closing herself off to the truth, which is that this is an unimaginable horror. Her memoir is an important voice that reminds us that we must not turn away from that which is profoundly tragic and fear-inducing. Facing it is the only way to maintain our shared humanity.

Ades, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the director of global women’s health at the NYU School of Medicine, holds both an M.D. and an M.P.H.