Cheryl Finley ’86

A simple abolitionist illustration of human beings packed like cargo into the suffocating lower decks of a slave ship retains all its heart-stopping power. In Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon, art historian Cheryl Finley ’86 details the history behind the image.

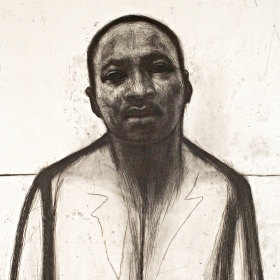

Cheryl Finley ’86 signs books at the Featherstone Center for the Arts in Oak Bluffs, Mass.

First printed in 1788, the simple abolitionist illustration of human beings packed like cargo into the suffocating lower decks of a slave ship retains all its heart-stopping power. In her recent book Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon, art historian Cheryl Finley ’86 details the history behind this schematic and examines the art that has risen from it since the early 1900s. Cheryl, who coined the term “slave ship icon,” analyzes paintings, sculptures, photomontages, stained glass windows, and installations recalling the Middle Passage—the stage of the trade route by which millions of Africans were forcibly sent to the Americas—in the context of various cultural movements.

Now an associate professor of art history at Cornell and a research associate at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, Cheryl was a Spanish major at Wellesley and simultaneously held a work-study position in the art department. Her interests were intense and varied, but she eventually became apprentice to an art appraiser, which combined her passions for art and economics. In the course of her work, Cheryl would go to art auctions. “The only other people of color there would be ‘the help’—security guards or art handlers,” she says. This was a frustrating discovery. “I’m really interested in the art market,” she explains, “and one of the things that motivated me to get my Ph.D. was to try to figure out a way to be part of a system that would inspire black people to collect art.”

Cheryl pursued a Ph.D. in African American studies and history of art at Yale. While taking a course at the Yale Center for British Art on the “long 18th century,” she felt that her fellow students were unaware that the money for art collections of the era had been made in the transatlantic slave trade. She decided to do a project on maps based on privateering in the slave trade, eventually traveling to Liverpool, Hull, and Bristol to examine their archives. While she was researching, she “came across the slave ship icon as a mnemonic for black history,” a single image encapsulating the horror of forced diaspora and the struggle for freedom.

Two years later, during the course of her research on the icon, Cheryl went to Ghana for the first time and visited old fortresses of the slave trade. Once there, she felt the “psychic residue of 500 years of tragedy, where people are being pulled away from their families and their homeland.” Even on a hot, stuffy, noisy bus, crowded with people and chickens, she got chills at the sight of the Cape Coast Castle, a fortress Cheryl discusses at length in a chapter on tourism inspired by the miniseries Roots.

Committed to Memory is exhaustively researched and examines how social and political movements intersected with the reclaiming of the slave ship icon. “These artists found it necessary to reignite this single image to talk about what’s happening in the world,” Cheryl explains. Some of the striking works of art in the book include Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons’ installation The Seven Powers Come by the Sea (1992), which joins the slave ship icon with Yoruba deities, and Hank Willis Thomas’ Afro-American Express (2004), a mock credit card bearing a famous image of a slave ship. The card has an expiry date 0f 08/63, referencing the March on Washington at which Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his “I have a dream” speech.

Cheryl says that the Akan people of Ghana use a word—sankofa—that means “one must return to the past in order to move forward.” As such, her book documents the importance of ritualized remembrance and of reappropriation. The slave ship icon in itself is an image of unspeakable trauma. Committed to Memory shows that artists continue to remember and reclaim it in a beautiful, extraordinary way.