Readers who believe in a post-racial America, in being color-blind in racially diverse situations, who are hoping for a kumbaya moment, are not going to have those needs met by Fleming’s book. But if they’re willing to let go of what they think they know about race and prejudice, Fleming will provide a bracing trip through how we do—and don’t—discuss race.

Crystal Fleming ’04

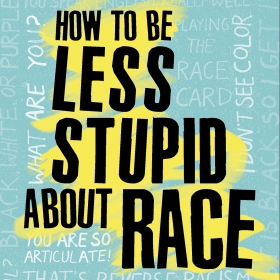

How to Be Less Stupid About Race

Beacon Press

230 pages, $23.95

I grew up a few hours down the road from Wellesley in New Haven, Conn. The summer before my freshman year, I was talking to a middle-aged white man at a barbecue he was hosting when he asked where I’d be going to school in a few weeks. I told him. His bonhomie evaporated immediately: “Wellesley,” he sniffed. “My daughter wanted to go to Wellesley. She didn’t get in.” He paused. “Of course, that’s when you had to be so smart to get in.”

Left unspoken but almost palpably implied: Being black is what got you in, and you’re taking the place of someone who isn’t black and should be there. Like my daughter.

I hadn’t thought of that man for years, but when I cracked open How to Be Less Stupid About Race by sociologist Crystal Fleming ’04, that memory popped right up. Like a lot of the examples in Fleming’s book, the disgruntled father in my story did not consider his remark racist, would have denied that intent completely, and perhaps would have told me I was imagining things, or too defensive, or one of the many other responses people who are stupid about race say. And a lot of black readers will nod their heads as they leaf through this book, and feel heard and validated.

Readers who believe in a post-racial America, in being color-blind in racially diverse situations, who are hoping for a kumbaya moment, are not going to have those needs met by Fleming’s book. But if they’re willing to let go of what they think they know about race and prejudice, Fleming will provide a bracing trip through how we do—and don’t—discuss race. She begins by explaining the origins of racial stupidity with a salient truth: “Hundreds of years after establishing a nation of colonial genocide and chattel slavery, people are kinda-sorta-maybe-possibly waking up to the sad reality that our racial politics are (still) garbage,” she writes. Nooses are still being left in workplaces. Black and brown people are consistently and shamelessly questioned by white ones about the right to be where they are—a Starbucks in Philadelphia, the neighborhood pool, a common room at an Ivy League university—followed by a call to the police to send them back where they belong.

Fleming dives into the inability of some white feminists to actually listen to their black feminist colleagues (because they don’t recognize that black women have been feminists without the label for decades). She examines the reasons for her eventual disillusion with Barack Obama in his second term. (“The stunning contrast between Obama’s patronizing speeches to black communities and his conciliatory response to violent police officers was as painful to witness as it was galvanizing.”) And she takes to task the New York Times’ (and much of the mainstream media’s) preoccupation with covering both sides of white supremacy. “The existential question that white folks keep struggling with—‘Should we listen to the white supremacist side now??’—only ever has had one answer: No.”

Fleming’s no-nonsense approach (she really does want us to do better) is just the guide we—all of us—need. Because with race, ignorance isn’t bliss—it’s dangerous.

Bates is a correspondent for Code Switch, NPR’s team that covers race and identity.