A year after the fire at Notre-Dame de Paris, the state of the cathedral still evokes tears. Why does the destruction of shared heritage touch us so deeply?

For me, the best of what these “ancients” left us keeps building on a shared sense of wonder, meaning, and identity. They elicit a sense of reverence, enriching us generation after generation.

Photo by Thomas Samson/AFP via Getty Images

Nine months after flames devoured much of Notre-Dame de Paris, I pulled up old videos of the blaze on my laptop and found myself inexplicably bawling—just as I’d dissolved into inexplicable sobs while watching those videos in real time on April 15, 2019.

Whatever lay behind all those unexpected tears?

It was no case of love at first sight that summer of 1972, when I was a rising Wellesley senior on the first stop of my first trip to Europe. Jet-lagged and exhausted, I remember being deeply disappointed when I approached the cathedral toward its flattish, western facade. From that vantage point, its storied bell towers looked squat and boxy, like a wedding cake whose baker had forgotten to mount its crowning layer. Only later, when I’d circled the entire perimeter—flying buttresses! rose windows! gargoyles!—then stepped inside to find all the heart-soaring space and light I’d been expecting, did my disappointment flip to delight.

Nearly 30 years after that initial visit, when I was living in Paris, my husband, toddler, father, and I often spent Sunday afternoons searching for winter sunlight in the tiny, sandy playground on the cathedral’s south flank overlooking the Seine.

In time, our daughter inherited a battered copy of the 1996 Disney video The Hunchback of Notre Dame; she and her best friend would alternate watching that animated, English-language film at our apartment, then switch to the 1998 video of the live French musical at her friend’s. She remembers her French Scout troop’s expeditions to Notre-Dame, and a school outing where her class learned medieval dance steps during a historical fair on the cathedral square.

My reporter husband remembers doing an interview in 2008 for the New York Times with the cathedral’s chief sacristan, whose job entailed responsibility for the computerized system that rings the ancient bells in lieu of Victor Hugo’s hunchback bell ringer, Quasimodo. John got a private tour of the forest of massive wooden beams—where last year’s fire started—in the unseen space between the cathedral’s lead roof and its vaulted stone ceiling.

Knowing John’s feet had walked the very beams that burned and tumbled into the nave a year ago made the fire seem more personal to me. But worldwide icons like Notre-Dame achieve their status precisely because they somehow speak beyond their own small world to humanity itself.

Like Notre-Dame, UNESCO’s 1,121 World Heritage sites—from the Incan citadel of Machu Picchu to the tomb of China’s first emperor with its terracotta warrior armies, from Iran’s archeological masterpiece at Persepolis to Africa’s Victoria Falls or Arizona’s Grand Canyon—are recognized for possessing outstanding cultural or natural importance that enrich humankind’s shared heritage.

Photo by Stephane de Sakutin/AFP via Getty Images

No wonder then that UNESCO Director General Audrey Azoulay, witnessing the flames devouring Notre-Dame, responded in a sense for all of us who watched in person or from afar: “We are filled with emotion, and our hearts are broken.”

What broke so many hearts? Why did so many respond so viscerally to those howling flames, that billowing smoke? Why were the world’s eyes so fixed upon that blazing spire as it lost its mooring, tipped, then toppled into the nave?

Some primordial fear of fire set me off, though my brain kept flashing me more logical, intellectual reasons for my intense distress: 850 years of “presence” suddenly ablaze. A multifaceted icon—of religion, culture, history, art, architecture, literature, film, tourism—in flames. The irony of an island cathedral, often described as the heart of the French nation, surrounded by water, burning out of control. Fire or not, my daughter reminds me that the brass marker of Point Zéro is set in the square fronting the cathedral. If the French want to find the distance from Paris to another spot, they measure it from there.

Logic and intellect prompted the start of what hit me and others that day, no matter what God, or gods, we worship or don’t. But long term, visceral, emotional responses felt most at play.

My stomach clenched as the fire quickly gutted not just the structure itself but my own multilayered sense of sacred space over time—voices reaching us across millennia. Those voices came from the ancient Parisii, a Gallic/Celtic tribe that controlled river traffic, and lived and worshipped on the island from about 250 B.C.E.; from the ancient Gallo-Romans who later built a temple to Jupiter on that same island; and later still from medieval Christians who razed a simpler, smaller church near the site to begin building Notre-Dame in 1160.

The blaze reminded me of the Taliban’s intentional dynamiting of the monumental Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan in 2001, an act that also made my stomach turn, no matter that I’d never seen those towering statues, that I wasn’t Buddhist. Nonetheless, as long as they stood, they somehow transmitted a message from the 6th-century humans who had carved them into the limestone cliffs. “Here is who we were,” they seemed to say. “Here is what we could do.”

It was the same message the medieval builders of Notre-Dame—or the prehistoric cave painters at Altamira, for that matter—seemed to hand down through the centuries, leaving successive generations awed by their extraordinary prowess. Whether they were creating masterworks as large as Notre-Dame or as small as a mini-bison daubed onto a rocky cave wall in northern Spain, both creations possess the power to be as alive to us today as if they had just been completed.

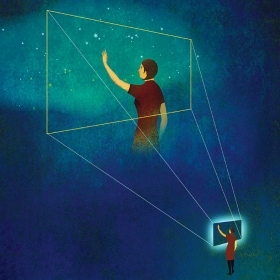

For me, the best of what these “ancients” left us keeps building on a shared sense of wonder, meaning, and identity. They elicit a sense of reverence, enriching us generation after generation, and allow us to “see ourselves as riders on the earth together … brothers who know now they are truly brothers,” as poet Archibald MacLeish wrote in 1968, six months before man would walk on the surface of the moon.

Philippe Petit/Paris Match/Getty Images

Any shaky sense of world stability—perhaps memory of world stability is a better way to phrase it these days—that I might have been clinging to disappeared in flames a little more than a year ago. That the cathedral burned during Holy Week—an ironic message from the heavens?—meant that all the religious panoply of Easter, the holiest day of Christianity’s liturgical year, had to be hurriedly transferred to a nearby church. Christmas, however, brought the sucker punch, when Notre-Dame’s pastor announced that though the cathedral walls were still standing, experts were giving them only a 50 percent chance of survival.

2019 marked the first Easter and Christmas since shortly after the French Revolution—when the cathedral had been shuttered and turned into a warehouse—that no services were held in Notre-Dame. That closure only added to my sense of general unease in a world already suffering a plethora of unnatural natural disasters: rising ocean levels, melting glaciers and polar caps, relentless temperature fluctuations, wildfires, earthquakes, mudslides, surging hurricane activity, and, at home, mid-February temperatures so mild that irises in our Connecticut garden already showed several inches of “spring” growth. And now there is COVID-19.

François Cheng, a Chinese-born scholar-poet-calligrapher and a revered member of France’s Académie Française, struck a national chord during a television appearance after the blaze when he compared the cathedral fire to a “maternal presence” torn from her children, plunging them into infinite sadness and regret. “We say to ourselves: There are so many things that I could have told her, and we never did. We never even told her, I love you.” Speaking of the moment when the blazing spire finally toppled and fell, he described being seized by a “cry of horror,” explaining: “Our Lady is going to leave without any time for us to bid her adieu.”

Last September, a day before returning to the U.S. after spending the summer in France, I decided I’d better bid my adieu to Notre-Dame, just in case she didn’t make it. I joined thousands of others milling about, vying for a view from the Left Bank sidewalk that runs along the river. Many came for a once-in-a-lifetime look. Others seemed to have come to mourn some loss, their own, or humanity’s.

A towering crane hung over the closed-off disaster site that hot, sunny day. The cathedral windows, glass removed, looked trim behind transparent covers, but the overall effect, of a blinded soul, was chilling. The flying buttresses, one of the cathedral’s glories, were themselves buttressed by wooden supports to help keep the walls standing. Metal scaffolding erected as part of the pre-blaze reconstruction clung to the remains of the roof in a tangle, much of it melted and fused together by the fire’s heat. Officials know that unholy tangle will have to be un-made before Notre-Dame can begin to be re-made. Unknown is whether today’s workers can remove it without provoking catastrophic damage.

As I gawked at the ruins that morning, thoughts and emotions flitted by. Notre-Dame, our Lady, our mother, your mother, my mother: the closest thing to a goddess figure in all of Christianity. Would the church have spoken to so many, I wondered, had she been named Sainte Frénégonde or Sainte Plectrude?

A 50-50 chance that her walls will survive hardly seems like reassuring odds. Those stone walls—baked, burned, scorched—may upon closer inspection be found to have softened beyond repair, like the walls of fire-bombed buildings in Berlin after the onslaught of World War II bombing raids.

Broken hearts led to an unprecedented, worldwide avalanche of donations to rebuild once President Emmanuel Macron vowed—with the fire still burning—to see the cathedral restored within five years. Given the extent of the damage, it’s a timeline unlikely to be met.

Perhaps today’s builders might be wise to ditch Macron’s timeline, and simply rebuild at a steady pace till the job finds itself finished, just as their medieval counterparts continued building the structure until there was nothing more to build. The timeline isn’t the crux of the matter, nor whether the restoration is an exact or approximate reproduction of the building at any chosen moment in time.

At bottom, perhaps, we need to help keep the voices of the original builders audible, to keep their voices from joining the fainter echoes of the civilizations who preceded them. How best to keep up the conversation? Perhaps by reminding tomorrow’s generations that if we stop trying to listen, they’ll surely stop trying to speak.

Paula Butturini ’73, a former foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and UPI, lived in France from 1999 to 2014. She now spends half the year in her childhood home in Connecticut, and much of the rest of her time in a stone farmhouse in central France.