Jessica Griffiths ’00 began her love affair with birds in the suburbs north of Chicago. “Our backyard backed up to a woodland,” she says. “The area was zoned as a flood plain, so it couldn’t be developed. It was a few acres of deciduous woodland. I would rush home from school—I was 14, mind you—and I’d get a pair of binoculars, I think they were from my grandpa. They were unbelievably heavy military binoculars. But that was what we had. And I would go out birding in those woods.”

When Griffiths got to Wellesley, she discovered a club called WABAN, which stood for Wellesley Amateur Bird-Watchers and Naturalists. WABAN’s faculty sponsor, Professor Emeritus of Biological Sciences Nicholas Rodenhouse, would become Griffith’s major advisor.

“When I was a sophomore, he asked me if I wanted a job. It was a summer internship working on his field research at Hubbard Brook in New Hampshire. It was bird work. I still remember him telling me about it, and me being like, ‘Wait, wait. Are you telling me you’re going to pay me to walk around in the forest and look at birds?’ After that summer, I knew, ‘Well, this is what I’m going to do now,’” Griffiths says.

It would be a peripatetic life. Now a biologist for a California environmental consulting firm, Griffiths spent the first few years after Wellesley traveling around the country working for nonprofits and government agencies in seven states, with a focus on songbird ecology and monarch butterfly migration. She worked as a wildlife biologist at the Big Sur Ornithology Lab, counted bird nests in Yosemite, and coordinated citizen scientists doing the annual Christmas Bird Counts sponsored by the Audubon Society.

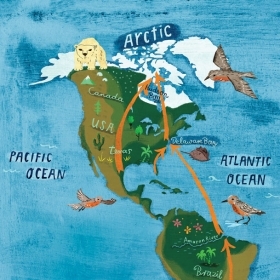

So Griffiths was not surprised when Science magazine published a study titled “Decline of the North American Avifauna” in its Oct. 4, 2019, issue. Ken Rosenberg, a senior scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the American Bird Conservancy, was the lead author, along with scientists from the National Wildlife Research Centre in Ottawa, the Canadian Wildlife Service, and others. The laconic title notwithstanding, the article sounds an emergency call, revealing that the North American continent has lost nearly 3 billion birds across 529 species over the last 50 years. This means there are 29 percent fewer birds in the United States and Canada today than in 1970. Of the nearly 3 billion birds lost, 90 percent came from just 12 families, including familiar birds such as sparrows, warblers, finches, and swallows.

‘People have been talking about the extinction crisis, and we’ve seen rare species decline or go extinct. But when even our common species have declined so drastically, it’s very hard to imagine that there aren’t significant holes in the tapestry of our world and that at some point, it’s really going to fray.’

—Carola Haas ’83, professor of wildlife ecology at Virginia Tech

Interconnected factors are responsible for the decline. Agriculture and habitat loss are likely the primary causes, though climate change, declining insect populations, light pollution, glass window panes on buildings, and outdoor cats also play a role.

“One of the things that came out in this study is that the guild of birds that shows the most serious decline is grassland birds,” says Griffiths. “I did a summer internship in 1999 for the U.S. Geological Survey doing grassland bird surveys. At the research station I worked at, [we gathered] all kinds of information on how grassland birds were declining precipitously then, more than 20 years ago. So when this paper came out and I saw it, I was like, yup, they’re still in trouble.”

Carola Haas ’83, professor of wildlife ecology in the department of fish and wildlife conservation at Virginia Tech, wasn’t surprised by the Science article either. Haas’ research centers on wildlife populations in managed ecosystems, with a focus on breeding and movement behavior of amphibians, birds, and reptiles.

“It’s a very powerful paper,” Haas says. “It’s shocking in terms of the magnitude, but everybody had a sense that this was going on. But to be able to really quantify it in that way was different. You know, in certain political climates, nobody cares about these things, but it’s easier to make more effective arguments when you can quantify what’s happening.”

To arrive at the mind-boggling numbers, the authors of the study used on-the-ground tallies carried out over decades by amateur bird-watchers—including the annual North American Breeding Bird Survey and the Christmas Bird Count. Their observations provided a wealth of data that the researchers cross-referenced with information from 143 weather radars designed to detect rain but also discern biomass—the groups of hundreds of migratory bird species moving through the skies in fall and spring. Measurements revealed that the volume of spring migration has dropped 14 percent in the past decade.

“People have been talking about the extinction crisis, and we’ve seen rare species decline or go extinct,” says Haas. “But when even our common species have declined so drastically, it’s very hard to imagine that there aren’t significant holes in the tapestry of our world and that at some point, it’s really going to fray.”

Some Good News

“One of the really great things about this paper, too, is that it was not a universal decline,” Haas points out. “There are very, very severe declines that they identified, and that could help [scientists] prioritize where to work. But there was this one clear success story with waterfowl. And that’s something, because when I started my career in the ’70s and ’80s, waterfowl were in horrible condition.” The study documents that populations of wetland birds such as ducks, geese, and swans are flourishing, showing a 56 percent increase over the past 50 years.

Haas credits action in both the public and private sector for the improvement. “The amount of effort that went into habitat protection for wetlands was huge,” she says. “Changing hunting regulations and the massive investment in habitat protection totally turned things around for waterfowl. The Science paper was really inspiring in showing that if we make the investment in habitat conservation, we can turn things around. And that’s really just what we need to do, to be thoughtful about not sprawling out, and to have natural areas.”

It’s important to note the resurgence of waterfowl, Haas adds, because “it’s a huge success story. It shows it can be done. And that’s the kind of thing that I think keeps most of us going. That, and the fact that most of the public wants to do it, too. If you do surveys of people and ask what would they want to spend money on, there is lots of public support for spending money on conservation.”

Lara Jones ’18 is a field technician studying acorn woodpeckers in California. Since graduation, she has done fieldwork on a variety of bird projects from New Hampshire to Florida to Oregon, and is slated to start graduate work on cerulean warblers at Ball State University in Indiana. She says, “There are definitely success stories that show that legislation and things like the Migratory Bird Act can have a big, positive impact on saving endangered species. Bald eagles and raptors have been doing really well, in large part because of banning DDT, which harmed their eggs. Similarly, the California condor is a success story. And wetland birds have also been on the rise. Things like that that show that if we can get the right people into office and really advocate for conservation, it can make a huge impact.”

Small Changes, Large Effects

Jessica Griffiths was glad to see the Science study get widespread play in the media. “It got huge headlines. It got a lot of traction,” she says. “So many people emailed me! The New York Times wrote an op-ed that publicized it. It’s really good that people are aware that this [decline] is happening,” she says. “I stay optimistic, because the more we can get the word out that there are concrete things that the average person can do to make a difference, the better. The fact that it is backyard birds declining, while that is awful, helps people form a connection and helps them see that there are things they can do in their own backyards that can improve habitat and help the birds out.”

Griffiths says that because so many backyard birds are insectivores, it helps to create an environment that attracts insects. Plant nectar plants and blooming flowers, and plants that bloom at multiple times of year. Don’t use herbicide, she advises. Put out a bird bath. Have water. Have food. Have shelter. And keep your cat indoors.

“Any lifestyle changes that are environmentally beneficial will be good for birds,” Griffiths says. “So use less water, drive less, reduce your carbon footprint, eat organic—all those things have trickle-down effects.”

Lara Jones adds, “You also can help birds by contributing to organizations that do direct management or that raise awareness or advocacy. Right now, the current administration is doing everything in its power to completely gut as many environmental protections as possible. And one of those is the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. They’ve proposed changes to that rule and to the Endangered Species Act that would really remove some pretty serious protections that are in place. It’s important to raise that kind of awareness and get people politically involved. Call your representative and apply that political pressure!”

Photo by Kristof Zysowski

A siskin, a type of finch

Photo by Lillian King/Getty Images

Photography courtesy of Macaulay Library at Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Looking to the Future

Emily Dickinson wrote, “Hope is the thing with feathers.” The College is doing its part to raise awareness for the need for wildlife conservation—including birds. The Paulson Ecology of Place Initiative, now in its third year, seeks to inspire and prepare students across disciplines to engage with the natural environment and develop a sense of place on campus. Paulson events and programs range from in-depth ecology studies to field observation, bird-watching, owl prowls, and the gathering of nature observations for an Emily Dickinson class. “We are working hard to instill in the Wellesley community the care and connection to nature that is needed,” says Suzanne Langridge, director of the initiative. “Considering we had 20 hardy souls at a rainy, cold, winter tree walk last week during Winterfest, I feel that there is hope!”

Sometimes, hope can be hard to come by. In the classroom, Jaclyn Hatala Matthes, assistant professor of biology, teaches lessons in the reality of ecological change. She says it can be difficult to take in news like the Science study. “This is the trend we see in a lot of different ecosystems … with the number of species that are disappearing. It’s more than we can think about,” she says. “The first couple of years, I felt really depressed when I was teaching all this stuff. Then I saw that my students were feeling the same way. Since then, I’ve tried to reframe [environmental science] as an urgent opportunity for action. If we’re going to do something about this, we need to do something now. We have this window of opportunity to be able to think about what we want the world to look like for the next 50 years.”

Matthes says her students often talk about climate anxiety and its effect on mental health. “They think about the weight of all the things that they’re going to have to deal with,” she says. “They feel the pressure of having to live in a world where we don’t know what’s going to happen, where there are going to be more natural disasters and all of these things like bird decline.”

But Matthes has also been inspired by the way Wellesley students are responding. “Especially this past year, we’ve seen this huge surge in climate activism among both our students and, more broadly, people across the U.S., where they’re just connecting these issues to other things that they really care about, like thinking about how this ties to race, and how this ties to inequality, and how this ties to economic forces, as well.”

Take Dayna De La Cruz ’21, a biological sciences major who studied in Peru this semester. “We [learned] different concepts of conservation—conservation biology, conservation science, community-based conservation. We [studied] the history of exploitation of indigenous people such as the rubber boom, and the culture and language of indigenous people.”

De La Cruz grew up in Houston. “I believe my interest in conservation began from documentaries or shows that I watched as a child on Animal Planet as it all appeared like a distant and mythical land, as someone that was coming from a city,” she says. “But my passion truly grew stronger after having my first summer field season at Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire.” She did additional field research at Harvard Forest in Petersham, Mass., the following summer.

“Being able to be in the presence of nature and experiencing all the amazing biodiversity in action gave me this instinct to protect it at all costs,” she says. “The more I learn about the vulnerability of nature, the more interested I become in conserving it.”

While she believes young people need to take political action and make personal behavioral change to combat climate change and conserve nature, De La Cruz thinks a simpler action is just as important.

“Go out and hike, or backpack, or walk in a park,” she says. “Attempt to get closer to nature, to get to know nature, as [you] will slowly grow fonder of it. This does not even have to require much traveling; it could be as simple as observing a bird or a bee in your backyard for a couple of minutes. Being out and being connected will help spread awareness of the need for conservation.”

Seven Steps to Save Birds

Field biologist Lara Jones ’18 steered us to the website 3billionbirds.org, which details seven actions people can take to help birds. Go to the website for more information. They are:

1. Make windows safer

Install screens or use paint, film, string, or tape to break up reflections on glass. Read more at bit.ly/safewindowsforbirds.

2. Keep cats indoors

Even well-fed felines instinctively hunt and kill birds.

3. Reduce lawns, and plant native species

Plants provide shelter and nesting areas, attract insects, and offer additional food sources such as nectar, seeds, and berries.

4. Avoid pesticides

Many widely used insecticides and weed killers are toxic to birds.

5. Drink bird-friendly, shade-grown coffee

Shade-grown coffee requires less fertilizer than crops grown in full sun and preserves forest canopies where migratory birds winter.

6. Reduce the use of plastics

One recent study found that 80 percent of seabirds have ingested plastic, confusing it with food. (See bit.ly/birdsplastics.)

7. Watch birds, and share what you see

The Audubon Society offers tips on how to get started (bit.ly/startbirding), as does Cornell’s Bird Academy (academy.allaboutbirds.org).

Catherine O’Neill Grace, a senior associate editor for this magazine, enjoys bird-watching at the Broadmoor Wildlife Sanctuary near Wellesley.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.