Anti-grade-inflation policies come of age

Grade inflation is like the weather: Everyone talks about it, but no one does anything about it. Well, almost no one. For 10 years, Wellesley has pioneered an approach to grading that seeks to rein...

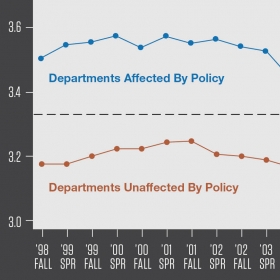

Graph source: “The Effects of an Anti-Grade-Inflation Policy at Wellesley College,” by Kristin F. Butcher ’86, Patrick J. McEwan, and Akila Weerapana. Based on student transcript data. Enlarge

Grade inflation is like the weather: Everyone talks about it, but no one does anything about it. Well, almost no one. For 10 years, Wellesley has pioneered an approach to grading that seeks to rein in the spiraling A’s that most observers of American higher education—including those sitting on graduate admissions committees or weighing merit-based scholarship applications—agree are clouding any meaningful assessment of student accomplishment. As grade inflation has become rampant, grade compression has followed—a phenomenon where all the grades in a class cluster at the top of the spectrum. The tyranny of the A’s has diluted the value of the most excellent work.

Fighting grade inflation is a risky business, of course; it’s hardly an easy sell to tell students they’re better off receiving a more accurate assessment of their skills—and getting potentially lower grades while they’re at it. But at Wellesley, grades had gotten conspicuously high in the years leading up to the change in policy in 2004, even in relation to peer institutions.

“We were at the stage where there was concern that the rigor of a Wellesley education would be called into question,” says Richard French, the College’s dean of academic affairs. “It had gotten to the point where it felt like a pass-fail system. It didn’t provide any granularity for students about what they were good at and what they weren’t good at.”

The new policy, approved by faculty in 2003 and upheld in two later votes, said that average grades in 100- and 200-level courses with at least 10 students should not exceed a 3.33, or a B+. The hope was not only to loosen compression but also to even out grades across disciplines, perhaps encouraging more students to major in the lower-grading sciences. Students were justifiably concerned; would Wellesley’s action put them at a disadvantage against peers in the job market or graduate admissions? And some faculty balked, citing breaches to academic freedom or undue tampering with discipline-specific norms.

‘It serves the vast majority of our students well to be able to say, “I went to a rigorous college where students are held to the highest standards, and grades really mean something there.”’

Amid the lively campus debate, what has been missing is any independent sense of what the policy has actually accomplished. That’s what makes a rigorous new analysis by a trio of Wellesley economists so welcome.

As described in the summer 2014 Journal of Economic Perspectives, the policy quickly met its main goal of curbing the plethora of high grades, according to Kristin Butcher ’86, Patrick McEwan, and Akila Weerapana, all professors in the economics department. The researchers compared outcomes in departments that needed to lower grades to comply with the policy—most in the humanities and social sciences, in keeping with national trend—against those that did not. They found that after the policy change, students were about 18 percent less likely to get an A or A− in the affected departments. The number of B’s rose by about 17 percent. The changes also reduced the number of students graduating with magna cum laude honors.

The researchers did not find a substantial shift in majors from humanities to the sciences, although enrollments and majors in policy-affected courses did decline after the grading standard was in place. They found more notable movement from previously higher-grading to lower-grading fields within the social sciences.

The study also noted that students reacted to the tougher grades by lowering their evaluations of faculty in the affected departments. “This suggests that if we think grade inflation is a problem, it is unlikely to be self-correcting,” says Butcher. “There is no individual incentive to change.”

Even with an institutional mandate, change is hard. Although the College’s own research has showed no decline in graduate admission rates and although transcripts explain grading practices, calls for the policy’s reversal continue. And its disproportionate effect on underrepresented students—noted in the new study—will require remedy. Nevertheless, French insists, “it serves the vast majority of our students well to be able to say, ‘I went to a rigorous college where students are held to the highest standards, and grades really mean something there.’”

Click here to read the full article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives can be read here.