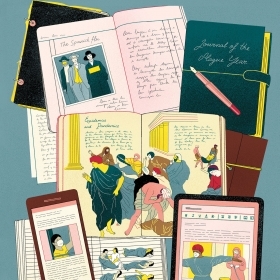

The magazine’s student assistant, Grace Ramsdell ’22, reflects on her pandemic-disrupted junior year, split between her grandmother’s home in Vermont and Claflin Hall.

Journal Entry #1: It seems like this is going to be our way of life well into summer, potentially.

As I write this, I am sitting against a tree. I am sitting against a tree looking at Lake Waban from above. I am sitting against a tree looking at Lake Waban from above, and it is so quiet. A few weeks ago, this spot of woods was slightly less quiet, as my English class gathered here for our last meeting and took turns reading aloud some favorite poems from the term. It was March 30, the anniversary of leaving campus last spring had passed two weeks before, and I just kept thinking—we weren’t here last year.

It’s a thought I’ve had almost every day since March 17 of this spring, the same date that students had to be fully moved out in 2020. But I felt the thought more urgently during that last English class meeting. I’ve had courses end remotely since last spring, but that day in the woods, my classmates and I were together and marking the end of something in a way that clicking “leave meeting” can’t replicate. It felt like we were choosing our ending. Maybe it was just an illusion of control, but in a time when we’ve come to understand the meaning of “uncertainty” on a whole new level, the illusion was comforting. Ending that English class outside on a sunny day in March on campus meant something, even if we were all wearing masks.

Though my year has not been without those new levels of uncertainty, I have also had an incredibly privileged experience of the pandemic. With my health and safety, I could look around this past fall and feel relatively normal—even as I looked around not at Wellesley’s campus nor at my home city of Cambridge, Mass., but at the Northeast Kingdom. At the town where my dad grew up, and where I was living with my grandma between August and November. Wellesley had asked that I take my junior year fall classes remotely. I figured there’d never be another time when I could just pick up and move to my grandma’s in Vermont for a few months—so I did it. In a big open landscape with no one around, there was a lot I could do on a daily basis without confronting visible signs of the pandemic. I would take long, maskless walks with a family friend’s dog (at age 7, Molly the black lab was my closest contemporary during those months) without crossing paths with anybody but the season’s woolly bear caterpillars.

I had never spent more than two weeks out of a city in my life, though, and I’d never been away from home for more than four. As time passed, absences became more pronounced. I would sit in the big red chair in my grandma’s kitchen, a seat I’d usually have to jockey for in the busy house, and I would see another scene superimposed over the empty space. The kitchen and adjoining dining room would be full of my dad’s people, who always come around for dinner when my family is in town. Grandma would have pulled a chair from the dining room table to sit on the border of the two spaces, between at least two different conversations. The woodstove would be glowing, but the curtain to the rest of the cold house would be open—we create too much heat.

In fall, I missed Wellesley, missed being surrounded by people my age. I wouldn’t trade that time with my grandma for anything, though. No one had come into her house since March until I arrived in August. She got plenty of yard visits in with friends before the cold weather, but for a woman who’d run a bed and breakfast for decades and who still had guests seemingly all the time in retirement, the house had been awfully empty. I was happy to join her, to stack her wood pile, to attend class over unpredictable Wi-Fi—even when that meant signing on from my aunt’s shed down the road, where there was a better connection. I was happier still when I won at Scrabble, when we took a foliage drive and stopped for maple creemees on the way home. Over the weeks and months, I photographed the big maple in the front yard turning. I learned that there is a time when the summer wildflowers coexist with the first autumn leaves. I loved stick season.

As I write this, I am sitting against a tree. (A different tree—I moved to follow the sun.) I am sitting against a tree looking at Lake Waban from above. I am sitting against a tree looking at Lake Waban from above, and it is so quiet. Not unlike leaving Vermont in November, it is hard for me to choose to stand up and leave this little corner of campus. I moved home from Wellesley in spring 2020 as a sophomore, and I came back 336 days later for the second half of my junior year. Somewhere in between departure and return, the inevitable reality that my time as a Wellesley student will end came to rest closer to the front of my mind. If there’s one thing that my fall reminded me, though, it was how to appreciate waking up in the same place every day while it lasted, noticing the little signs of time passing around me.

When I got back to Wellesley for the spring semester, I was jittery for weeks. Everything was exciting to me. I checked out seven books on my first trip to the art library. I stayed after class to talk with friends and my professor without a thought for the time, without wondering if there was somewhere else I should be. And I have found myself photographing the same scenes day after day. I am continually struck by my surroundings at Wellesley—and by the fact that with each day that goes by, I still get to be here, watching the light shifting and the time passing.

On the last day of my English class in March, the poem I read aloud was Emily Dickinson’s “We grow accustomed to the Dark.” Dickinson writes about the uncertainty of our first steps away from lightness, before we “fit our Vision to the Dark –.” This applies, as well, to “larger – Darknesses – / Those Evenings of the Brain –,” Dickinson tells us. Whether the darkness is literal or figurative, Dickinson writes that at some point, the lighting changes, or something in our sight adjusts to it, “And Life steps almost straight.”

A few days after the term ended, I was walking back to Tower Court with my friend and English classmate. It was around 10:45 p.m., and we passed the turn onto the lake path that also leads to the spot where our class had read in the woods, the spot where I write this. The day had been warm, but the night air was definitely chilly. The sky was clear, though, and nobody could say what the next day would bring. What if we went to that place right now, I said to my friend—half joking, then suddenly not. She said I was being ridiculous. I don’t remember what I said next that changed her mind. (I think maybe she just remembered that she’s ridiculous, too.) We turned and headed along the lake path.

Now, considering at that point I’d only been to this spot once before, I’ll admit it was a bit senseless to try to find our way here in the night. But our eyes did grow accustomed to the dark, and other than one instance of a startled goose startling us back, it was an uneventful walk. We climbed the hill to reach this place, and we looked at Lake Waban from above as it glittered with the lights of campus. When we looked up, we could see stars through the still-bare trees. So much remains wildly uncertain in our world today. In the quiet reverence of the time we spent like that, looking up, I thought about the year we’ve had. I also thought about the poetry spoken in that same spot a few days before and the joy of gathering as a group. It was a joy to be there with just one friend, too. These are the moments when life steps almost straight.

Grace Ramsdell ’22 is Wellesley magazine’s student assistant, an English and creative writing major, and a photographer. At the start of the pandemic, she revived her childhood passion for journaling. Most of the photos featured in this piece were shot on film.