The past year has been extraordinary. The COVID-19 pandemic has utterly recast all our lives—how we work and learn, play and pray—and it has been going on so long now that in the United States it has begun to feel, if not normal, at least “ordinary.”

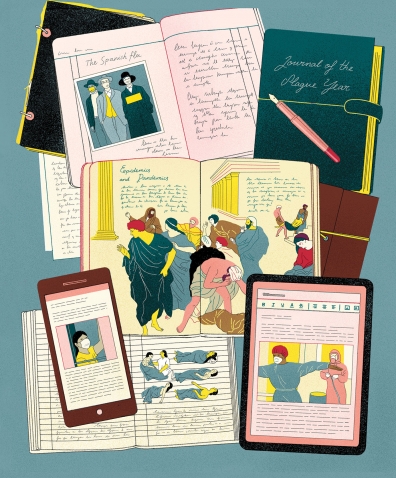

“We love, we hate, we covet, all in privacy and solitude,” Daniel Defoe wrote, of the alienation that stems from isolation, in his novel/memoir of the London Plague of 1665. One way humans have tried to fill that solitude is through personal journals. Many of us found ourselves in the early days of lockdown searching for solace in the great literature of pandemics. Sales of Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year and Albert Camus’ The Plague (another novel in the style of a diary) soared, as have recent novels that chronicle pandemics, including Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and Severance by Ling Ma. Some of us began keeping diaries, or, if we were already diarists, we began keeping them religiously.

For Wellesley anthropology professor Anastasia Karakasidou, the personal journal is an important tool both for people trying to make sense of their place in the world and for the academic trying to make sense of a society at a particular moment in history. For nearly 20 years, Karakasidou has made use of journals as part of her teaching and research into the cultures of cancer, drawing participants from Wellesley, China, and her native Greece.

So when the pandemic hit, she knew instantly what she must do. “I felt the best way for me to deal with this is to teach a class on pandemics,” she says. “The students are the greatest resources I have in my life right now to make sense of the virus.”

During the third term this past spring, she taught a seminar, Epidemics and Pandemics, that traced widespread outbreaks throughout human history, from Neolithic times to the present, and had students submit personal journals responding to what they were learning.

“Reading about past experiences of pandemics and bringing that into conversation about what it means to you—even if it’s the Plague of Athens or the Black Death—helps [the students] make sense of their personal experiences,” says Karakasidou. “The role of the pandemic diaries is to have the lived experience of COVID and how we can make anthropological sense out of it.”

In the pages of the students’ journals, stories unfold of family members falling ill with the virus, enforced isolation, and uncertainty about a vaccine. The themes that emerge from their writings are the perennial themes of pandemics: the needs of the individual versus the needs of the community, health disparities between socioeconomic and racial groups, as well as scapegoating, violence, and conspiracy theories.

“[My students] had barely come of age. They were still figuring out who they were—what is normal, what is not normal in their own culture—when all of a sudden, everything came to a halt,” Karakasidou says. “I see that they are shocked, and I wanted to capture that sense of culture shock through the diaries, to help them communicate that experience and figure out that they are not alone.”

A Bare Life

In late December 2020, as a third, massive wave of infections swept across the U.S., a sophomore (who prefers to be known only by her surname, Long), embarked on a trip home to China, where, by that time, the virus was under control.

It would have been a white-knuckle journey for anyone, but especially for a 19-year-old traveling internationally alone. Border restrictions were changing on a daily basis as she boarded a flight from Boston to Los Angeles, spent two days testing negative for COVID, then flew to mainland China. There, her baggage was fully sanitized by officers at the airport, and she was taken by government officials to a hotel. The only human contact she had for the next 14 days was with the hotel staff, garbed in full PPE, who brought meals to her door three times a day.

In a journal entry written after her ordeal was finally over, Long wrote that during her monthlong journey she felt “reduced to a bare life.” She referenced a reading from class by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben that mentions the plight of Homo sacer: in ancient Roman society, an outlaw who has had his rights as a citizen revoked. Unable to leave her hotel room, deprived of movement or company, “I felt I was a new version of Homo sacer,” Long wrote.

Usually, her homecomings are greeted with invitations from friends and family, but this time, people avoided her, even long after her quarantine had ended. “When I finally got back, I was treated as ‘one of those dangerous people who came from abroad,’” she wrote. “Many Chinese citizens considered Chinese students studying abroad as carriers of the virus and ‘the group that chooses capitalism and now wants to come back to the warm nest.’”

Her journals are full of unique cross-cultural insights and carefully crafted intellectual arguments. One entry traces the competing narratives within China and the U.S. that the other country was the source of the outbreak. Another dissects how China’s containment of the virus has reinforced the Communist Party narrative that its political structure is superior, its culture ascendant.

Long hopes to go on to earn a Ph.D. in anthropology, and she is already doing serious work in the field. Last year, she completed an independent research study in the new branch of anthropology called cyber ethnography, which uses the tools of anthropology to study online communities and interactions. Her journal entries are peppered with web citations and screen grabs from the Chinese social media platform Weibo, accompanied by her own English translations—each entry a lasting anthropological document. “I just don’t want people to forget the pain during the epidemic,” she says.

Kept in the Dark

Faith Hernandez ’22 missed the first week of remote classes last winter because a once-in-a-century polar vortex had plunged her hometown of Houston into chaos. “I did not have power, water. I hadn’t eaten for more than 24 hours, and it was getting really, really cold,” she wrote in a journal entry dated Feb. 16.

To keep warm, her family lit a fire in their fireplace for the first time. (Hernandez had always assumed it was merely decorative.) After a cousin’s roof caved in from the weight of the ice and snow, they invited extended family to join them, even though five out of the seven members of her household had only recently recovered from the coronavirus. “No one was concerned about COVID-19 because … we had another silent killer we felt we needed to deal with first: the cold,” she wrote.

The city opened “warming shelters” for the public, where social distancing was impossible. Still, hundreds of Texans trying to keep warm in their homes died from house fires and carbon-monoxide poisoning and exposure.

Days stretched into a week. Her dog shivered all the time. Periodically, her family would sit in their car for additional warmth and to charge their phones to get news of the outside world. “Where were our leaders? What efforts were being made to aid Texas?” she wrote. That’s when she got a crash course in one of the biggest lessons of pandemics: government failure. It would be a major theme in her journal entries for the rest of the term.

Reading the news on her phone, she learned that even though several Southern states were experiencing extreme weather, only the Texas power grid had failed, because for political and economic reasons, the state’s leaders had decided a generation ago to stay independent of the national grid. No one was coming to help them. Meanwhile, residents of Houston’s wealthier neighborhoods had their power back on within 24 hours.

“We didn’t have power for four or five days, and we didn’t have water for a week and a half,” she says. To add insult to injury, she says, the news broke that Texas Sen. Ted Cruz had hopped on a plane to Cancún, Mexico, with his family, while Texans froze.

Her readings during the semester led her to understand that this is often the case in pandemics, whether during an outbreak of cholera in the 19th century or coronavirus in the 21st. “Politicians—people in power—have a big impact on communities, especially during times of crisis,” Hernandez says. “I felt like our political leaders kept us in the dark and fled. It just goes to show that if you don’t have money or power or status, you are kept in the dark, quite literally. We felt we were left to die.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.