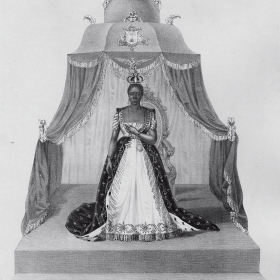

A lithograph of Empress Adelina, a member of the Haitian royal family, is part of the “Album Imperial d’Haiti,” dated 1852. This set of 12 pages is part of the Elbert Collection in Special Collections in the Margaret Clapp Library, which contains some 800 volumes on slavery, emancipation, and Reconstruction.

Album Imperial d’Haiti, 1852, 12 leaves of plates: portraits; 31 x 42 cm

She stares directly and unflinchingly at the viewer, arrayed in her coronation finery, dignified and somber.

This is Empress Adelina, a member of the Haitian royal family. She is depicted in a collection of lithographs commemorating the coronation of her husband, Faustin-Élie Soulouque, as Emperor Faustin I of Haiti. Born into slavery, Faustin I became a freedom fighter, was made president in 1847, and then crowned himself emperor in 1849. This “Album Imperial d’Haiti” comprises 12 lithographs derived from original daguerreotypes by A. Hartmann, dated and copyrighted in 1852. The images were produced in a set of 500; some were published in places like the Illustrated London News.

This set of 12 pages is part of the Elbert Collection in Special Collections in the Margaret Clapp Library. Donated by Ella Smith Elbert, class of 1888, the second Black graduate of Wellesley, and her husband, Samuel G. Elbert, in 1938, and added to until 1955, the Elbert Collection contains some 800 volumes on slavery, emancipation, and Reconstruction.

Associate Professor of History Ryan Quintana and his students studied the album in HIST 261: The Civil War and the World. The class is “a history of emancipation, what’s happening globally with the end of slavery, so it starts with Haiti,” Quintana says. “A lot of the materials we were looking at were negative caricatures, racist caricatures. The images in the album are a counter to that. I asked the students, ‘Here’s something that was produced by Haitians about Haiti. How is it different?’”

Historian Karen Salt considered Faustin I in her book The Unfinished Revolution. Though a brutal ruler, Faustin I played a significant role in altering mid-19th-century attitudes about Haiti, she writes, by “offering up a new currency—Black sovereignty. … [He] attempted to normalize images and language that commingled blackness, power, and politics.”

The album is “visually stunning,” says Quintana, and provides “powerful counters to the perception of Black sovereignty in the 19th century, made in the face of people’s lack of belief that something like a Black republic could ever exist.”