Wellesley's Edible Garden

Alumnae environmentalists return to campus for the Project Handprint Symposium

In September, the Camilla Chandler Frost ’47 Center for the Environment hosted the 2022 Project Handprint Symposium, which focused on the theme of health and environmental justice.

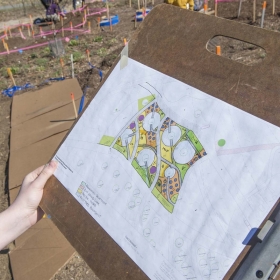

Courtney Streett ’09 speaks in the Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden.

On September 24, the Camilla Chandler Frost ’47 Center for the Environment hosted the 2022 Project Handprint Symposium, which brought Wellesley students, faculty, and alums together to focus on the theme of health and environmental justice.

Erich Hatala Matthes, associate professor of philosophy and director of the Frost Center, and President Paula A. Johnson kicked off the symposium, last hosted in 2013, with a call to action. As important as it is to minimize our environmental footprint, Johnson said, “It is equally important that we spend time examining the ways we can make a positive impact on the environment. That is the idea behind the term ‘handprint.’”

Priya Gandbhir ’09, an attorney at the Conservation Law Foundation, spoke about environmental law and policy alongside Charlotte Benishek ’16, a joint M.B.A. and master of environmental management candidate at the Yale Center for Business and the Environment. Gandbhir, a founder of Wellesley’s sustainability co-op, The Scoop, said climate change poses a significant threat to human health and emphasized that our priority “needs to be ensuring those who have already suffered the most aren’t overburdened by transition.” Benishek discussed the value of “personal and persistent communication” and of sharing first-person stories, using the example of a constituent who told her about the impact of PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) on his life, health, and community. Benishek has since advocated for revised laws and guidelines regarding PFAS levels.

[supporting-images]

Meanwhile, Courtney Streett ’09 gave a tour of the Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden through an Indigenous knowledge lens. A former television producer, Streett is the co-founder, president, and executive director of the Native Roots Farm Foundation, which she created to purchase the farm that had been owned by her great-grandparents, members of Delaware’s Nanticoke Indian Tribe. She showed the crowd a number of plants and trees, including the giant white oak, sweet goldenrod, a pawpaw tree (mahchikpia in Lenape), and a staghorn sumac, and described their uses by Indigenous peoples.

Later, Shani Fletcher ’98, director of the city of Boston’s new Office of Urban Agriculture, GrowBoston, and Catherine McCandless ’14, an urban planner at the Climate Ready Boston initiative, explained how Boston is preparing for climate change. McCandless gave an overview of coastal resilience solutions for East Boston and Charlestown. In all her work, McCandless engages many stakeholders in the local communities to develop solutions that provide multiple benefits. Fletcher described the many advantages urban agriculture provides, including a more resilient local food system, heat and stormwater mitigation, nutritious foods and healthy communities, and more. Her office hopes to create food production spaces in senior centers, schools, and Boston Housing Authority sites, as well as help existing urban farmers expand their capacity.

Dominique Hazzard ’12, a doctoral student in history at John Hopkins University who previously worked at the nonprofit DC Greens, spoke about using oral history to influence local environmental policy. Hazzard showed the food apartheid in Washington, D.C., in numbers: The district’s Ward 3, which is 81% white and relatively affluent, has one grocery store for every 9,336 residents, while Ward 8, which is 92% Black and has a much lower median household income, has one for every 85,160 residents. But Hazzard pointed out that it is not just sharing data but rather how we share data that is important: “Narratives both shape how people understand the problem, and the types of solutions that people can imagine to fix the problem,” she said, adding that the pervasive and limited narrative of Black residents “burning all the grocery stores down” in the 1968 protests has perpetuated the food desert problem.

Roheeni Saxena ’08, a public health researcher and educator, closed out the day with a virtual presentation on environmental exposures and neurocognitive outcomes. She discussed a study done in rural Bangladesh that quantified how exposure to metals, such as cadmium and magnesium in road dust and drinking water, damages cognition in children and adolescents. Participants’ blood-metal levels were far above average, affecting their learning. Saxena said health disparities are a matter of environmental justice. Children in a poor village who are exposed to metals “may stop going to school and never leave their village, creating economic immobility that can affect them and their descendants.”

“Climate change is perhaps the most grave challenge we face as a global society,” Johnson told the symposium participants. “I am so proud of the way that the alumnae gathered here today emphasize climate justice in their work. They have rolled their sleeves up to drive the positive change they wish to make in the world.”