What is the future of the College library as e-books and digitization become more common? Whatever happens,Clapp will still house books—including the priceless core collection donated by founder Henry Durant.

What is the future of the College library as e-books and digitization become more common? Whatever happens, Clapp will still house books—including the priceless core collection donated by founder Henry Durant.

When MaryBeth Kery ’15 arrived at Wellesley, she gravitated to Margaret Clapp Library immediately—and no wonder. She grew up hanging around her librarian mother’s circulation desk, where after school she sometimes turned her hand to cutting out paper snowflakes for seasonal decorations.

A computer-science major interested in human-computer interaction, Kery has logged countless hours working at the Clapp circulation desk during her time at the College—and she loves the place. “It’s so tranquil,” she says.

Although she still checks out plenty of books for students and faculty, Kery says she has seen a marked shift toward e-book and e-journal use over the last three years, and “we’re circulating a zillion iPads now.”

Library staffers also have observed that patrons aren’t using the stacks as much as they did only a couple of years ago. They’re searching for spots in which to study. But digging through the shelves? Not so much. Patterns of use at Clapp echo trends at academic libraries all over the country. What transformation the library will have undergone by the time Kery comes back for her fifth reunion is impossible to predict.

But in 2020, the heart of the collection will still be the 7,600 volumes that Henry Durant donated to the College at its founding—comprising rare books as well as titles from his working library. Durant had the radical idea for 1875—a time when access to rare books was essentially unknown outside the Ivy League—that women ought to have the opportunity to use primary sources. So from the beginning, Wellesley has sought a more expansive definition of an academic library. Through time, growth and change have been constant themes.

Burgeoning with Books

Three years after the College opened, the library collection had expanded to some 16,000 volumes and more than 100 periodicals, and it was arranged in a dedicated wing of College Hall. By the early 20th century, the collection had outgrown the wing. In 1905, philanthropist Andrew Carnegie offered Wellesley $125,000 for a new library building on the condition that the College raise an equal amount for an endowment, which was accomplished by 1907. On June 5, 1909, Pauline Durant laid the cornerstone of the neoclassical Indiana limestone edifice that—three significant renovations and additions later—still welcomes students today.

The building opened in 1910, the books having been moved down the hill from College Hall (thankfully, given the devastating fire that lay ahead) onto the new shelves during spring vacation. Alumnae donated the beloved statues of the Lemnian Athena, goddess of wisdom, and Hestia Guistiniani, goddess of the hearth, to flank the imposing bronze doors added in 1911.

The library’s first addition was begun just five years later in 1915 to provide a range of new rooms: a recreational reading room; space to house the growing collection of rare books; offices; archives; a reserve reading room; and additional stacks. By 1921, the library housed 95,000 volumes and several thousand pamphlets and subscribed to about 350 periodicals, according to the Wellesley College Library Handbook published that year.

‘Humankind has created an extraordinary variety of spaces in which to read, to think, to dream, and to celebrate knowledge. As long as humankind continues to value these activities, it will continue to build places to house them. Whether they will involve books or will still becalled libraries, only time will tell.’

More Typewriters, Please!

Responding to new technology has been a constant in the life of the library, both at Wellesley and around the country. In 1939, Vitalizing the Library, an American Library Association publication by Byron Lamar Johnson, noted the challenge of accommodating new media: “The concept of library materials is expanded to include not only books, periodicals, and other printed materials, but also pictures, music, scores, phonograph records, and motion pictures,” Johnson wrote.

By midcentury, Wellesley’s library needed even more space. In 1955, this magazine devoted an entire issue to the library, looking at plans for remodeling it and considering its future. In her article, “The Library in Prospect,” Miss Helen M. Brown, the Wellesley librarian, discussed the College’s need not only to address the problem of storage for the ever-growing book collection but also “the demand for adequate typing facilities in the library [that] reached such a pitch last year that editorials demanding them appeared in the Wellesley News. It is certain that more and more students are using typewriters for extensive notetaking and for writing papers.”

The structure was doubled in size with the addition of a new wing on the west side in 1956. The change had been inevitable, Brown wrote—but it did not come without some cost. “The old building has its drawbacks in the way of poor ventilation, dimness, over-crowding and inconvenience, but it does have dignity, a great many books, and an aura of scholarship,” she wrote. “It is our plan to let in fresh air, light, space, and modern efficiency without destroying the atmosphere or distinction of the present structure.”

In 1974, the library was named for former president Margaret Clapp ’30, and construction began on a third addition. The building that alumnae, students, and faculty know today—furnished with comfortable armchairs strategically overlooking Lake Waban—was finally complete.

Enter “LTS”

Fast-forward to 1994. In the wake of the dizzying transformation wrought by the desktop computer, and in anticipation of the internet, the College merged the library and computing staffs to form an “information services” division. As one of the first academic institutions in the country to do so, Wellesley became a national leader for this approach.

“There’s a lot of synergy between technology and library, when it comes to information,” says Ravi Ravishanker, Wellesley’s chief information officer. “This notion of a merged technology and library organization is one of the reasons why I took this job.” The merged department today is called Library & Technology Services (LTS), with a staff of about 80 people divided among information technology, library collections, and research and instructional-support functions.

The library began collecting electronic books in 2003, increasing the number of titles available to patrons while reducing the pressure on stack space. Today, users may access more than 658,000 e-books. The volumes offer different degrees of functionality, such as the ability to download, and some restrictions, including limitations on printing. But e-books are in the virtual stacks to stay.

Patrons also have access to more than 88,000 journals, an enormous increase over the 4,500 available when print predominated. The College continues to acquire some 8,000 print books annually. Clapp also maintains relationships with other libraries so that students and faculty can take advantage of the holdings of collections around the world.

Together with 16 other academic and research libraries in New England, the College is an active member of the Boston Library Consortium, which provides sharing of print, digital, and electronic content across the member libraries. The group offers a forum for a broad range of members, and acts as an incubator for projects and initiatives important to academic and research libraries in the 21st century. For example, through the consortium, last spring Wellesley signed on to a strong letter to the editor of The Chronicle of Higher Education decrying a steep upcoming price increase for e-books by some commercial publishers and university presses. (Many publishers charge libraries for e-books based on a model that combines payment for short-term use of a title with the purchase of the title after a few uses. This allows libraries to pay full price for an e-book that meets the needs of multiple readers, but much less for those that are checked out by only one or two people.)

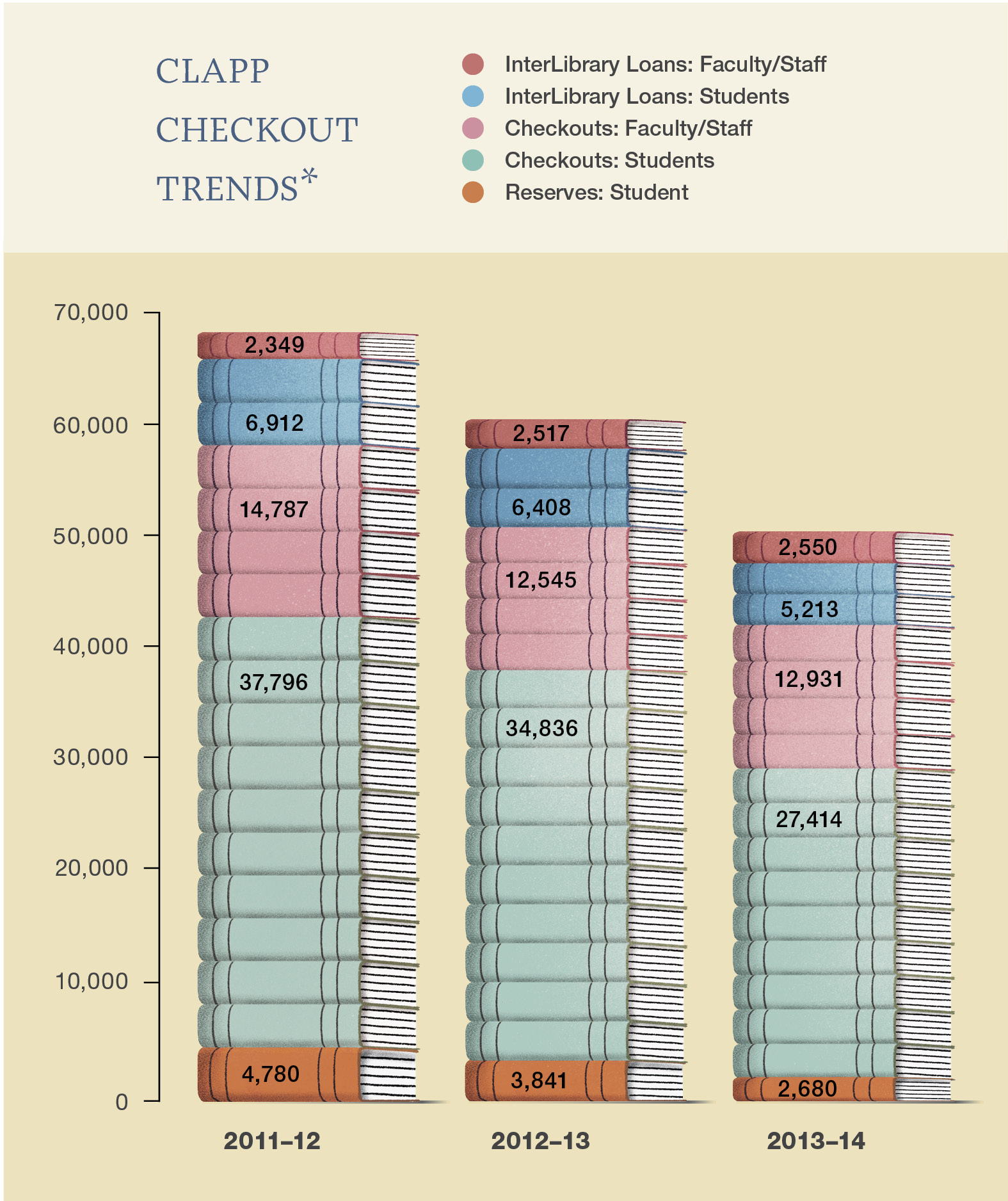

*Checkouts include books, audio/visual, scores, and more. Enlarge

Source: Wellesley LTS

Making Space

With digital publishing growing, deciding how and what to acquire for the library is no longer a matter of simply paying for this season’s new crop of books, monographs, and magazines. Director of Library Collections Ian Graham says, “In the print-to-digital transition that all libraries are navigating, thanks to some really good work years ago, we’ve gone nearly entirely electronic for periodicals—we’re out ahead of any other libraries that I’m aware of. The expectation is that people will have access immediately, and that we’ll have broad holdings—and we do.”

The transition to e-journals has cleared space in the former periodical room, opening up that area for other potential uses, including an “academic commons.” Though plans for it are in the early stages, Ravishanker envisions the commons as “a hub of academic activities,” which would include opportunities for one-on-one as well as group interactions. It’s possible that the writing and quantitative-reasoning programs might be located in the commons, as well as the library help desk.

The area would function as “a single place where [students] can get all the help that they need,” Ravishanker says. He also envisions a “maker space” within Clapp that will allow for experimentation with advanced technologies such as 3-D printers and 3-D scanners, a place where “interesting interdisciplinary work can take place. Artists trying to visualize digital data can work together there.” In addition to creating an academic commons in Clapp, according to the library’s long-range plan, “we are radically rethinking the branch library spaces on campus—art, music, and science.”

“As a space, this library is loved beyond comprehension,” Ravishanker says. “People come here all the time, use it, but they’re sitting with their laptops doing their work or collaborating with each other—they’re not using the stacks. So we’re trying to figure out how to position ourselves in a way that the space still plays an important part in the academic life of our students and the faculty, yet we still preserve some of the core elements.”

The Future of Books

But will there still be books? Both Ravishanker and Graham say yes—though with some equivocation.

“The trend is that the collection of physical books and monographs is not what it used to be,” says Ravishanker, adding that Clapp’s circulation statistics show a 50 percent decline in borrowing of physical books over three years. “Those who love books love books dearly, and they would argue that circulation statistics really don’t show the full picture—and they’re right. There are people who touch the books, browse the books. There are no statistics that show how much of that happens. However, there’s no denying that the physical book is losing its place in our lives.”

Says Graham, “In five years, there will certainly continue to be many, many books in the library. But in five years, we will probably be buying fewer print books, because there won’t be as many to buy. Nobody is saying ‘libraries without books’—that’s a vast oversimplification of a very complex transition that, at least from the library’s perspective, needs to be driven by the needs of the people who are using our institution.”

LTS planners envision a future library where an academic commons and space for new technologies will draw people to Clapp who are now using buildings other than the library. Ravishanker’s hope is that patrons will come to the commons, but “wander, get to the books, get to Special Collections.”

As the inevitable migration to digital holdings continues, the treasures in Special Collections retain their value—and their appeal. “Whether it is the history of science, the history of philosophy, language, geography, the history of ideas—it is here,” says Ruth Rogers, curator of Special Collections. “Wellesley’s collection is really far deeper than you would ever expect for a college this size. And that is greatly due to the vision of the founders.”

Graham adds, “We are finding more ways to use our unique collection to provide our researchers with real, immediate opportunities right here. Wellesley has amazing collections; these are things that have been built over more than a century around the core of the Durant collection. They’re unique, and as we acquire other things—collections, books, archives—students and faculty will have the opportunity to do research with primary sources here that they can’t do elsewhere.”

[supporting-images]

Providing Digital Access

In addition to connecting students with real objects, LTS is engaged in a variety of digital projects to make treasures such as the letters of 19th-century sculptor and poet Anne Whitney and the correspondence of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning available electronically. “These go out into the world, and it builds on itself,” says Graham. “People do scholarship that in turn inspires students here who do have immediate access.”

Jenifer Bartle, manager of Digital Scholarship Initiatives, works with faculty to develop projects that involve digitizing College holdings—including the Whitney letters and the hundreds of classical coins in the Mediterranean Teaching Collection. She says, “I very much appreciate the beautiful old objects themselves; my approach is to try to liberate the information that’s contained within them. Obviously, the physical objects are still important and need to be treasured. But the information that’s contained in them can take on a new life. With new digital scholarship tools and techniques available to us, we can bring the information contained in our unique collections to light in new ways.”

As electronic books, monographs, and journals continue to replace physical books in the Wellesley library, its unusually rich collection of rarities—from a ca. 500 b.c.e. fragment of a Book of the Dead papyrus to a Shakespeare & Company edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses—only become more valuable.

“More and more, what’s going to make Wellesley and any academic library proud—or at least recognized—is its unique materials, not its multiples,” says Rogers. “We’re seeing print through a different lens. We’re coming full circle to a point where scanning has made the book more available, has made text more available. The digital side has given everyone more access. But it’s also put a focus on those things that are tactile. The more we are exposed to an overflow of information, the easier it is to get access to words and information, the more important are our experiences with the tactile, the handmade.”

LTS statistics support the idea that Special Collections is playing a newly active role in the academic life of the College. The number of classes meeting in the space and using the materials has skyrocketed, with somewhere between 30 and 35 classes working with Special Collections every semester. Rogers believes part of the change is the result of younger faculty who arrive at Wellesley expecting to be able to use—and give their students exposure to—primary sources, something Henry Durant would surely approve.

The Library of 2020

When MaryBeth Kery and the rest of the class of 2015 return to campus for their fifth reunion, there will still be books in Clapp Library. What else will be there, staff members concede, is hard to predict. Perhaps a café in addition to an academic commons and a maker space? There will almost certainly still will be comfortable chairs overlooking the lake.

“People talk about a changing role for libraries,” says Graham. “I talk about an expanding role. We still do the core of what we have done all along; with e-books and e-journals, the process is different, but we are emphasizing things like special collections, archives, and digital humanities. The library does much more than it used to do; the library is no longer contained within the walls of Clapp.”

In the meantime, Kery will be putting in her last year at the circulation desk, sometimes recycling old entries from the card catalog to jot notes. She says she hopes the eventual creation of an academic commons will include more study spaces for students. “There’s a tension between being an institution and being a cozy place for students,” she says. “But [Clapp] has changed in some nice ways since I starting working here—now I think I could cut out and put up snowflakes for the holidays.”

[substory:1]

Catherine O’Neill Grace is a senior associate editor of Wellesley magazine. She has made a partial transition to reading e-books for certain genres, such as mysteries. For memoirs, history, and the arts, she still prefers (and purchases) hard-cover books.

Catherine O’Neill Grace is a senior associate editor of Wellesley magazine. She has made a partial transition to reading e-books for certain genres, such as mysteries. For memoirs, history, and the arts, she still prefers (and purchases) hard-cover books.