The “woman, life, freedom” movement shares the language and struggle of other uprisings worldwide.

The “woman, life, freedom” movement shares the language and struggle of other uprisings worldwide, writes anthropologist Narges Bajoghli ’04.

I first learned about feminist theory and feminist politics in the early 2000s at Wellesley, when everything was shadowed by the impact of 9/11 and the start of the war on terror. The popular narrative of the time was dominated by discussions about the need to save women in Afghanistan. In the classroom, some professors pushed us to think critically about the long history of racism in feminist movements and the utilization of “women’s issues” by states to engage in more violence. My classmates and I brought the concepts we were learning to heated debates on campus around the decisions of the George W. Bush administration. Nonetheless, dominant societal narratives had a strong undertone of pride that Western women were no longer being controlled by laws for the mere fact of being women, and thus had an obligation to “save” Afghan women from this fate.

Much has changed domestically and globally during the decades since I sat in seminars in Pendleton Hall and grappled with the history of feminist thought and practice. Most immediately, the Taliban are back in power after two decades of American war and occupation in Afghanistan, and the world has once again turned away from the reality of Afghan women.Western women now intimately understand that living under repressive gender laws is not solely a problem “over there,” but very much a contemporary reality, right here. In my own life, I have earned my doctorate in anthropology and become a feminist scholar of media, power, and resistance movements.

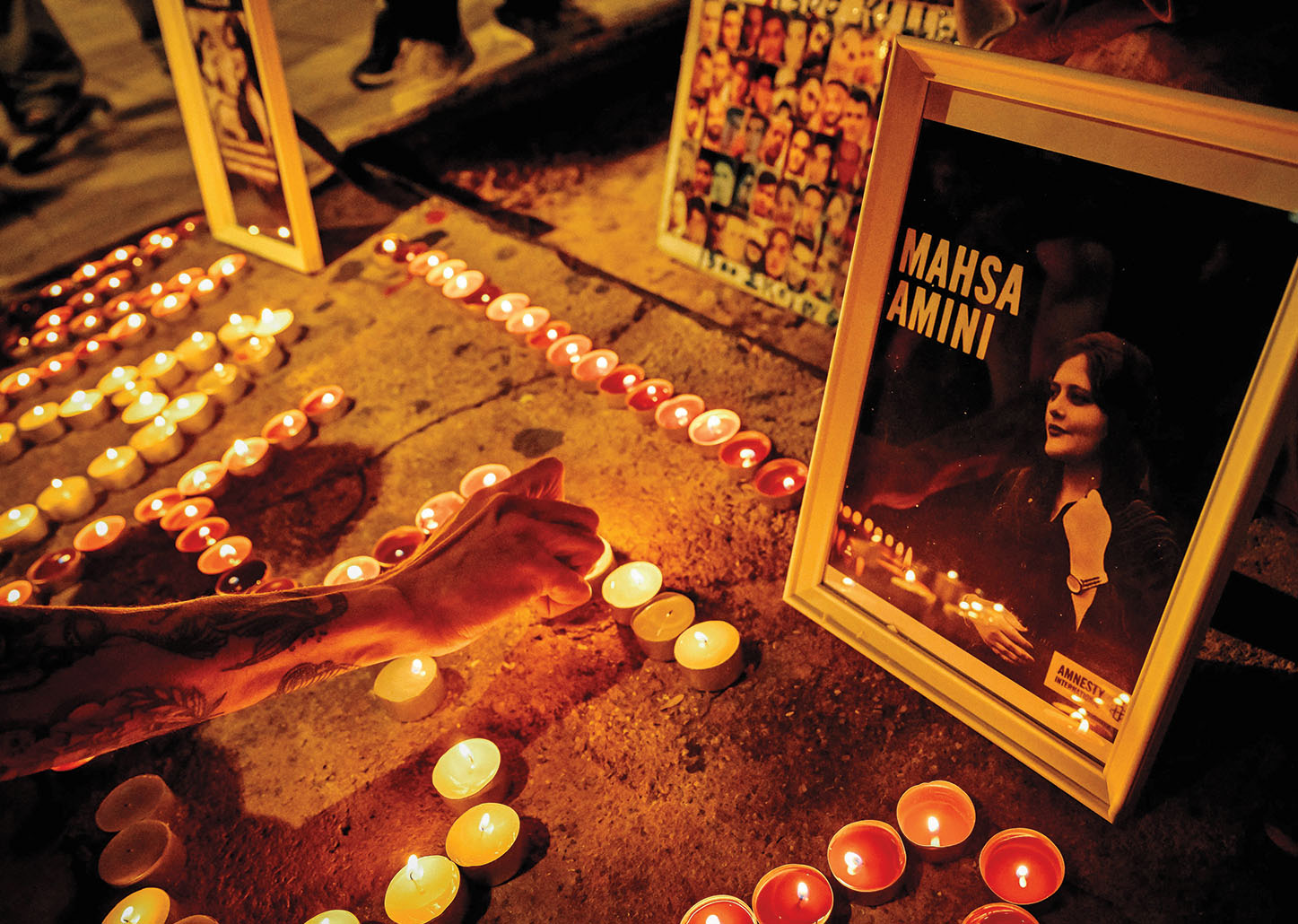

With this background, when the September 2022 “woman, life, freedom” movement spilled onto the streets across Iran, I immediately recognized it as a new militant feminist movement that would capture global attention. Anger had been mounting on Iranian social media since mid-September, when a picture of Jina “Mahsa” Amini in a coma began to circulate. She had been taken on a gurney to a hospital in Tehran from the morality police station, where she had been held for having “bad hijab.”

On Oct. 29, 2022, in Athens, Iranian refugees and Iranians living in Greece lit candles forming the name ‘Mahsa’ during a demonstration to commemorate 40 days from the death of Mahsa Amini.

Louisa Gouliamaki/Contributor/Getty Images

In the days Amini was still in a coma, Iranians expressed rage on social media platforms at the continued policing of their bodies and the senseless violence it entailed. With ultraconservatives in charge of all levers of power in Iran since 2021, the presence of the morality police had increased, and the new president was making the strict implementation of mandatory hijab a cornerstone of his administration. But Iranians had had enough.

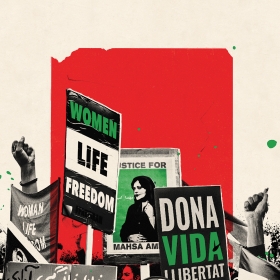

After Amini’s untimely death, female mourners at her funeral took off their veils and chanted in Kurdish, jin, jiyan, azadi (woman, life, freedom). The slogan, with a history in Kurdish movements for liberation, voiced that there can be no political liberation without women’s liberation. Cell phone video of the funeral circulated online, and “woman, life, freedom” was soon translated into Persian. The slogan’s radical demand predicated on life and freedom unleashed years of built-up rage and everyday resistance onto the streets, with women at the helm. Some men and young boys joined them in street protests. Women and young girls took off their veils and threw them into bonfires.

Since 1979, when the Islamic Republic came to power in Iran after a popular revolution, the state had made veiling mandatory not only for religious purposes, but because it represented the “committed revolutionary citizen”; today, women are standing in front of the very forces of state repression and refusing to enact a committed revolutionary citizenship any longer.

For nearly five months, intermittent street protests continued, despite widespread repression by state forces. As far as movements in post-revolutionary Iran go, the “woman, life, freedom” movement has not been able to turn out the huge numbers of protestors that some other movements have. Nonetheless, in the short time span since its inception, this movement has fundamentally shifted the contours of Iranian society and the Iranian state.

“Women in Iran are showing how toothless power is when people decide en masse to no longer comply.”

The conversation outside Iran has focused on whether this movement could topple the state. Yet, very soon after the street protests began, women and girls in Iran began to articulate that their fight is not only with the “morality police” of the state, but also with the fathers, brothers, and husbands who act like “morality police” at home. In doing so, women and young girls in Iran have taken aim at patriarchy as a whole and the myriad ways it manifests itself in daily life.

Movements led by women and students have been a constant thorn in the side of the Iranian state for decades and have posed some of the most serious challenges to its leadership. But something fundamentally shifted in September 2022: Masses of women and girls demonstrated that they were no longer afraid to militantly confront the state. Images went viral of young women unveiling and standing defiantly in front of groups of riot police, not backing down.

Something has broken in Iran. The repressive apparatuses of the state no longer work to induce obedience from women. The police and security forces can no longer make Iranian women obey mandatory hijab laws. Neither can vigilante pressure and violence. Shopkeepers and men on the streets are standing up against ultraconservative vigilantes who target women who have taken off their veils. In response, the state has announced it will install more cameras that use facial recognition technology to identify and fine women who refuse to obey. Yet the fines and threat of surveillance have not curbed the trend. Women in Iran are showing how toothless power is when people decide en masse to no longer comply.

Crucially, it is not only anti-state Iranian women who are actively standing their ground. Daughters of some prominent pro-regime families I have interviewed have also decided to no longer veil. Mothers of pro-regime families have become outspoken advocates of a woman’s right to choose whether or not to veil. The mothers, wives, and daughters of the very men who make up the power structures of the Islamic Republic publicly and privately challenge compulsory hijab and patriarchal norms. Whether pro- or anti-Islamic Republic, women across the political spectrum are making it known that the issue is not the veil, per se, but the compulsory nature of the law and taking bodily autonomy and choice away from women.

A woman cuts her hair at a rally called by Amnesty International, in front of the Iranian embassy in Madrid on Oct. 6, 2022.

Associated Press

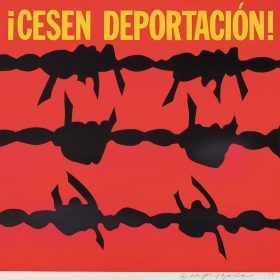

In these ways, the uprisings in Iran share the same language and struggle of other uprisings led by women and LGBTQ+ people worldwide that resist patriarchal violence and repression, from #NiUnaMenos to #MeToo to the many movements for reproductive justice and LGBTQ+ rights. This is why the “woman, life, freedom” movement has resonated so loudly for women in all parts of the world. Unlike in 2001 and the war on terror, the tenor of the conversation today is not “those Muslim women dealing with the veil and patriarchy,” but instead, “patriarchal control and domination is a problem we’re all fighting.”

It is no wonder that as wealth and power dramatically increase in the hands of a few, with parallel increases in monopolization of corporations, laws seeking to control women and transgender and nonbinary people become more expansive and repressive. As protests have spilled forth in societies around the world, more and more laws have been passed that criminalize the very act of protesting, including in democratic societies such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

Power, especially state power, is predicated on the domination of women and transgender and nonbinary people. For most of the history of nation-states, laws and norms have encoded women as property and as incapable of having sovereignty. In tandem, queerness has been criminalized and banned to differing degrees. Despite some changes in laws and norms around questions of gender and sexuality, we see all around us a backlash and an attempt to re-exert control.

As long as power is defined and practiced as domination over others, and as long as the norms of society are measured by patriarchal standards, women and transgender and nonbinary people are always vulnerable to repression. That is why at the heart of feminist movements around the world is not only a refusal to be an object of domination, but an attempt to put forth new visions for organizing societies away from domination and control and toward pluralistic coexistence built around freedom and care.

How we get there is the task before all of us. We are living in an era of global feminist uprisings that insist on organizing for holistic change. As in the best seminars I attended at Wellesley as a student, this task necessitates that we be willing to accept that others’ experiences may be radically different than our own, engage with each other to discuss difficult topics, learn new perspectives, and organize to challenge existing hierarchies. As Iranian women are showing us, we can choose en masse to no longer comply.

Narges Bajoghli ’04 is a writer, scholar, and educator. She is an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. Her books include the award-winning Iran Reframed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic (Stanford University Press, 2019) and the forthcoming How Sanctions Work: The Impact of Economic Warfare on Iran (Stanford University Press, 2024). She is a proud Wellesley alum.