Rarely has a symbol been more poignant and expressive than the “heech,” a calligraphic representation of the Farsi word for “nothingness,” which takes on a human shape and a nearly human-seeming character in the hands of Iranian sculptor Parviz Tanavoli. Far from being “nothing,” the heech symbolizes “the nothingness that voices the wholeness of being,” according to Tanavoli.

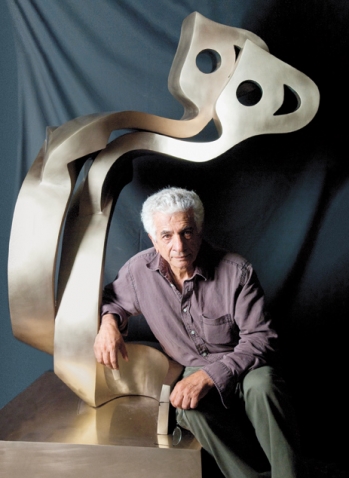

Visitors to the Davis Museum are treated to a garden of heeches rendered in bronze, fiberglass, ceramic, and neon (see back cover). They also encounter an awe-inspiring variety of sculpture, paintings, jewelry, and other work with motifs ranging from birds and antique locks to human hands and decorative gates created by Tanavoli (b. 1937), considered the father of Iranian modernist sculpture. The Davis exhibition is the first retrospective of Tanavoli’s work in 39 years, and the first ever in the United States.

Tanavoli’s work contains all the energy of Pop Art, a movement with which he became familiar as a visiting artist in Minneapolis in the 1960s. His sculpture, particularly that of birds, calls to mind the work of modernist masters like Brancusi.

In 1979, Tanavoli’s career was interrupted by the Iranian revolution. His ties to modernism and the West (he studied in Italy and traveled to the U.S.) made it difficult to continue exhibiting his work. Tanavoli left his university position and embarked on a tour of Iran, steeping himself in traditional Persian handicrafts and eventually writing more than two dozen books on topics such as tribal textiles and Persian metalwork. In 1989, Tanavoli emigrated to Vancouver, British Columbia, where he has remained above the political fray and maintains his relationship with both the West and Iran, returning to his country for part of each year to teach the next generation of sculptors.

“Tanavoli’s work shows his remarkable resilience and humanity,” says Lisa Fischman, Ruth Gordon Shapiro ’37 Director of the Davis Museum and curator of the retrospective with Shiva Balaghi of Brown University. “His work is not so much political as universal.”

“Parviz’s work lends itself not only to a simple reactive joy that each of us may experience in viewing particular pieces, but it is also informed by the 3,000-year-old Persian culture from which his art grows,” says Maryam Homayoun Eisler ’89. Eisler, who was born in Iran, and her husband have created a fund at Wellesley to provide a platform for research, exhibition, and scholarship on the visual arts of the Near, Middle, and Far East, the first of its kind at an American college or university. The Tanavoli retrospective is the first initiative within that project.

“I want to help bridge cultures and dispel stereotypes, to focus attention on the beauty and rich content of Persian culture,” she says. “Where politics fails, art and culture can win over people’s hearts and minds.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.