On Sept. 15, when the Cassini spacecraft runs out of fuel and dives into Saturn’s atmosphere in a final blaze of glory, it will be taking a little piece of Wellesley with it, metaphorically speaking. During the Cassini mission, Wellesley students from majors far and wide joined forces with Professor Richard French to calculate trajectories and crunch data, leaving their mark on a NASA mission that, for some, permanently imprinted itself on their own lives.

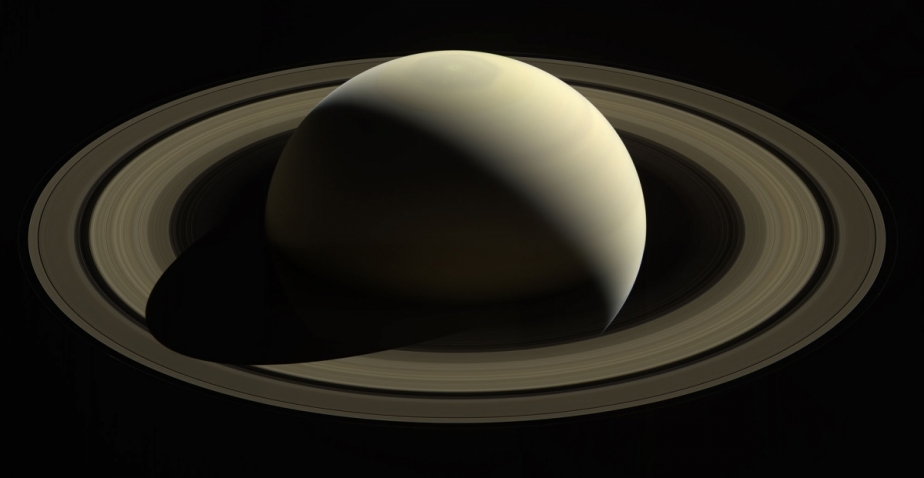

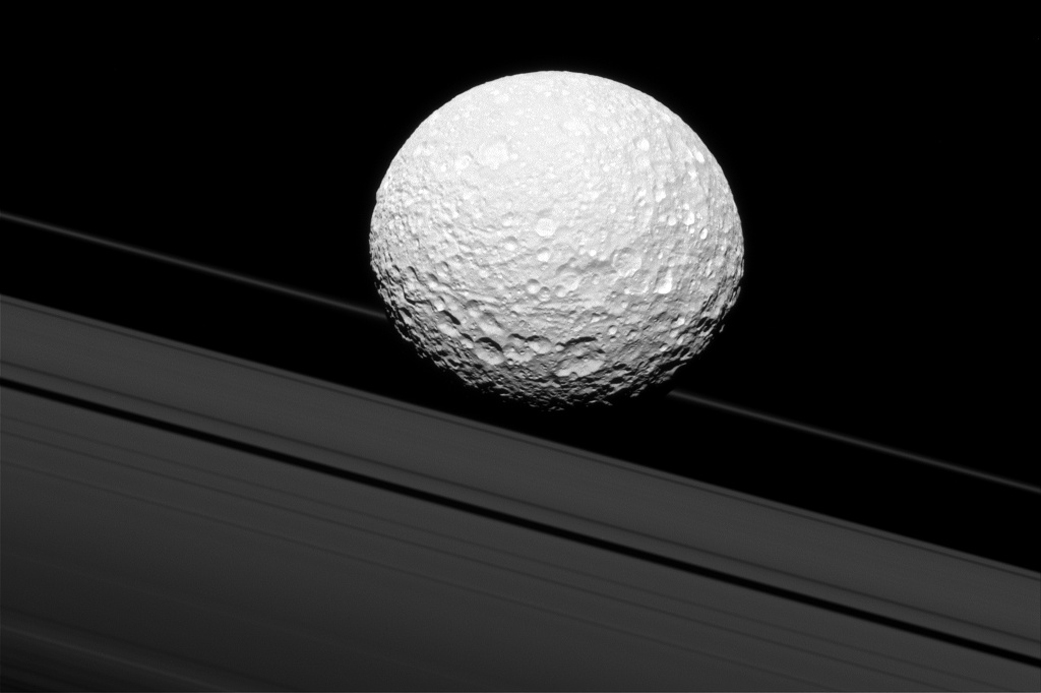

The Cassini mission started in the 1980s, when NASA teamed up with space agencies around the world to send a robotic spacecraft into orbit around Saturn in what French describes as an effort to “really explore Saturn in every dimension: its moons, its atmosphere, its rings, the planet itself.”

Of course, reaching Saturn is no small feat, and it wasn’t until 2004 that the spacecraft finally entered Saturn’s orbit. But once it did, French and a team of international scientists began gathering data from a dozen specialized scientific instruments.

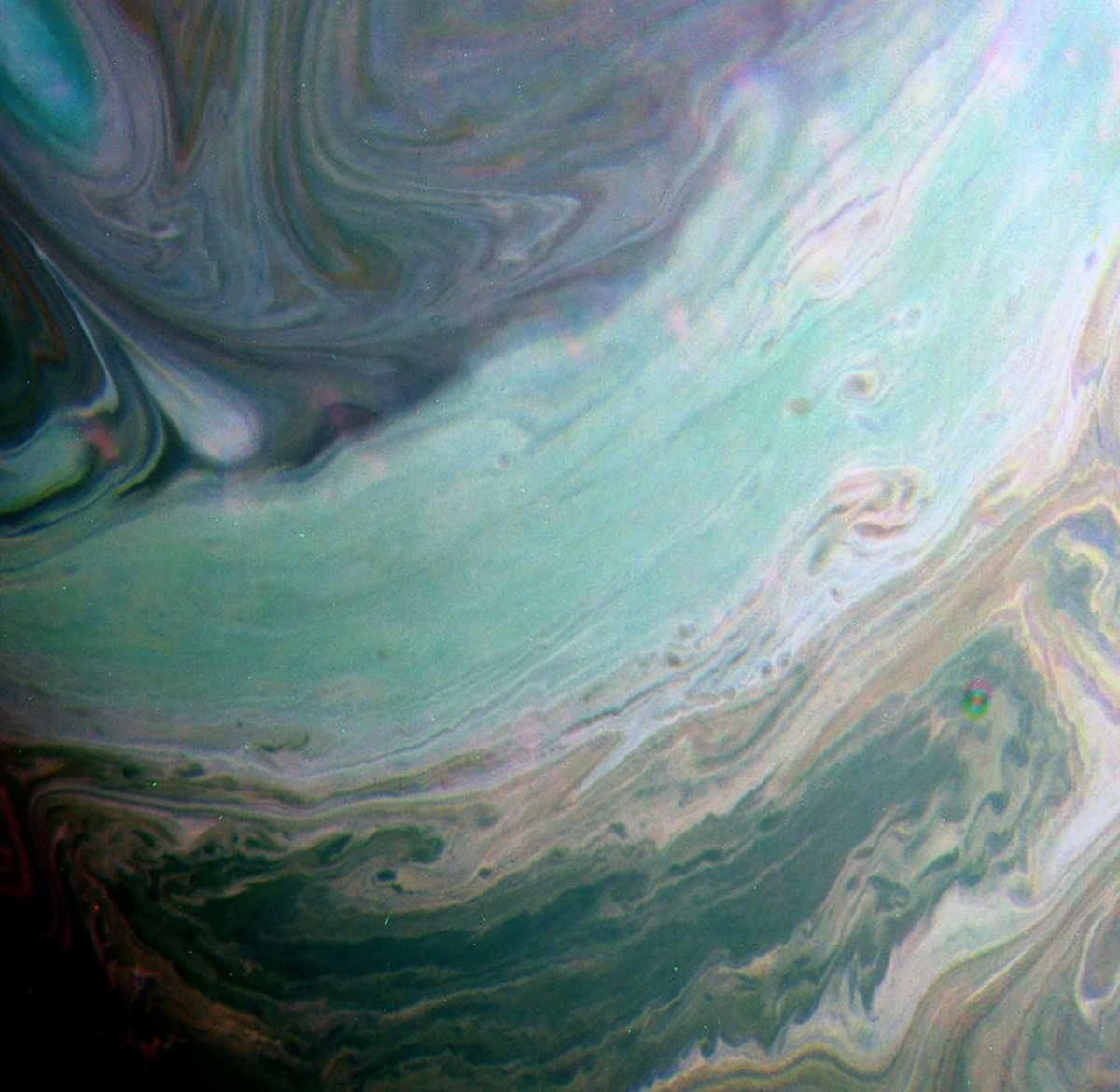

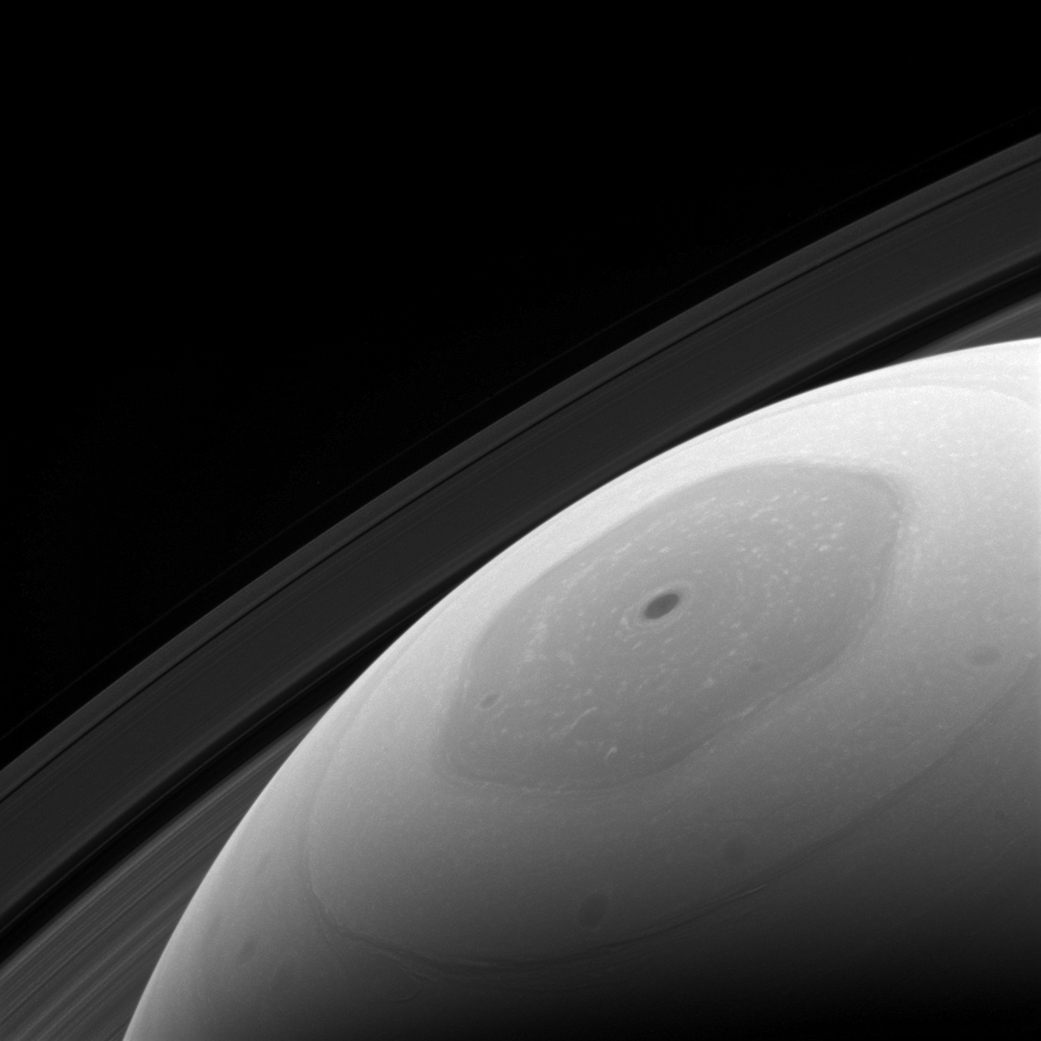

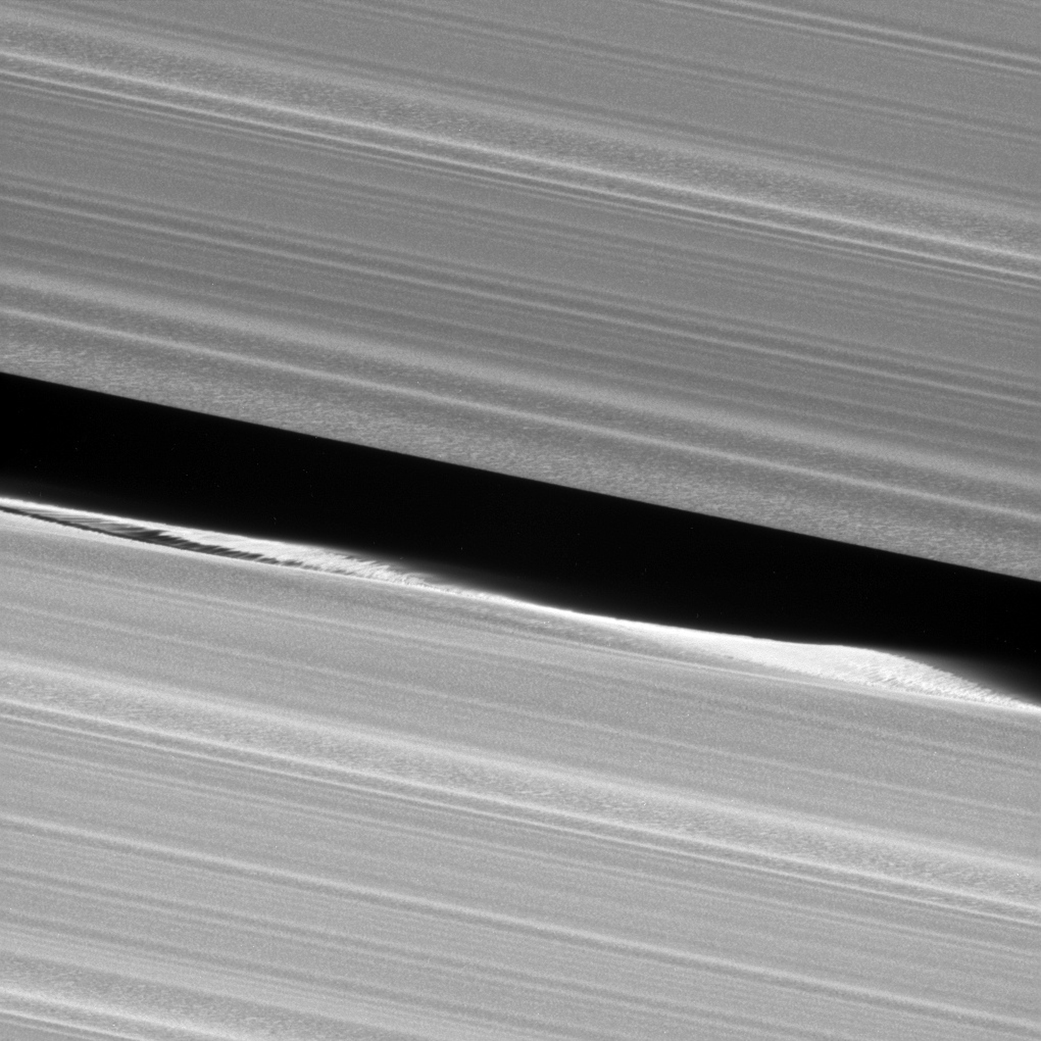

French, a planetary astronomer and professor of astrophysics and astronomy, worked with the radio-science instrument, which sent radio signals from the spacecraft to huge antennas on Earth. These radio signals were a useful tool: As they bounced off objects en route to Earth, they revealed information about those objects. One of French’s main projects involved analyzing data on how the signals bounced off Saturn’s rings to create “a profile of what the detailed structure of the rings is like.”

In 2008, French already had a pile of raw data on Saturn’s rings when he was tasked with figuring out the best orbital path for the radio science instrument through 2017. Suddenly, he had a realization.

“It struck me as a pretty rare opportunity to share in the excitement of working on a space mission with nonscientists, because the specific project that I had, there was work that could be done that didn’t require a lot of advanced coursework,” he explains.

French emailed his Astronomy 101 students, encouraging them to join his Cassini research team at Wellesley for the summer, even if they weren’t science majors. Two of those students were Katie Judd ’11 and Rachel Snyderman ’11, both first-years who had taken Astronomy 101 to get their lab requirement out of the way early, and found themselves unexpectedly hooked.

“I was so intrigued by the opportunity to participate in an ongoing research project, and I took what he said in his email to heart, that you don’t have to be a science major,” Judd recalls. “And so I applied.”

After a quick crash course in computer programming, data analysis, and the mission itself, Judd and Snyderman, along with the six other members of Team Cassini (and yes, there were T-shirts), were soon completely immersed in the day-to-day of NASA research. Their days were a flurry of coding and calculations as they worked on projects that ranged from analyzing data on Saturn’s rings to determining which orbits would yield the best data through the mission’s end.

“It was a pretty amazing feat of Professor French to include so many students so early on in our Wellesley careers, and to really let us put our hands on the steering wheel,” Snyderman says, adding that a few days after learning how to code for the first time, she found herself writing code to send up to the spacecraft.

The students also participated in calls with the entire international Cassini team, which offered a powerful lesson in what Snyderman calls “scientific diplomacy.”

“I remember it being fascinating because it didn’t become about one country’s mission. It became about something so much more than that,” Snyderman says. “Each Cassini research component—from the radio science to the rings and atmosphere teams—had their own stake and knowledge that they brought to the team, and it was all about concessions and compromises.”

But for Judd, the summer imparted something even more fundamental.

“In terms of my own mentality, it was so empowering to me to be told that I can do science and math. Honestly. That sounds so basic, but as somebody who was really under confident in those areas, it really made all the difference,” she says.

And while Judd majored in political science and Latin American studies, and Snyderman earned a degree in economics and Latin American studies, both went on to take more astronomy classes, and eagerly volunteered as team leaders when French decided to continue Team Cassini with a new crop of 24 students during the 2010 academic year.

“That summer kick started what I think was an incredibly rich part of my liberal-arts experience, even though it may not be reflected in my degree,” Judd says. “It carried through Wellesley, understanding that just because you’ve chosen one major or just because you feel like you’re more equipped for one area of study, doesn’t mean you shut yourself off to others.”

Today, both continue to draw on the quantitative skills and diplomatic lessons they learned that summer, Judd as a communications specialist at the U.S Agency for International Development, and Snyderman in the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

“I think for me it’s been neat because I’ve always wanted to go into public service and public service is all about working on something that is so much greater than yourself,” Snyderman says. “And this was really my first experience working on something like that, where the research, the mission, and the outcome were so much bigger than just me or my four years at Wellesley.”

And while neither landed in astronomy, Cassini has never strayed far from their minds: Judd recently started following the Cassini Facebook page, intrigued by the risky maneuvers the spacecraft has been attempting in its final days, while Snyderman’s current role has given her an inside look at how federal funding works for NASA programs like Cassini.

So in mid-September, when the Cassini spacecraft ends its decades-long mission in dramatic form, Judd and Snyderman, along with the rest of Team Cassini, will be able to look on knowing that the long hours they spent in the Wellesley observatory plowing through data and wrestling with calculations are part of what made the mission such a success.

Catherine Caruso ’10 is a Boston-based freelance science writer who has written for various publications, including Scientific American, MIT Technology Review, and STAT.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.