Photograph by Kathleen Dooher

My daughter was three days old when police from the farming town of Xiaxi drove her to the Social Welfare Institute in nearby Changzhou, a city of several million residents in Jiangsu Province, China. Presumably a stranger had found her after she’d been left on her own.

Hers was the fate of many girl babies in the 1990s, due to China’s one-child policy. It is likely that her birth parents thought they needed a son, or perhaps her paternal grandparents—who probably would have been the ones to name her—had pressured their son and his wife to abandon this girl baby so a grandson could be born. Local family-planning cadres enforced the regulations put in place by Jiangsu’s leaders, limiting each couple to one child, even in a rural family like hers. If parents pushed against family-planning rules, a hefty fine would ensue—at the very least.

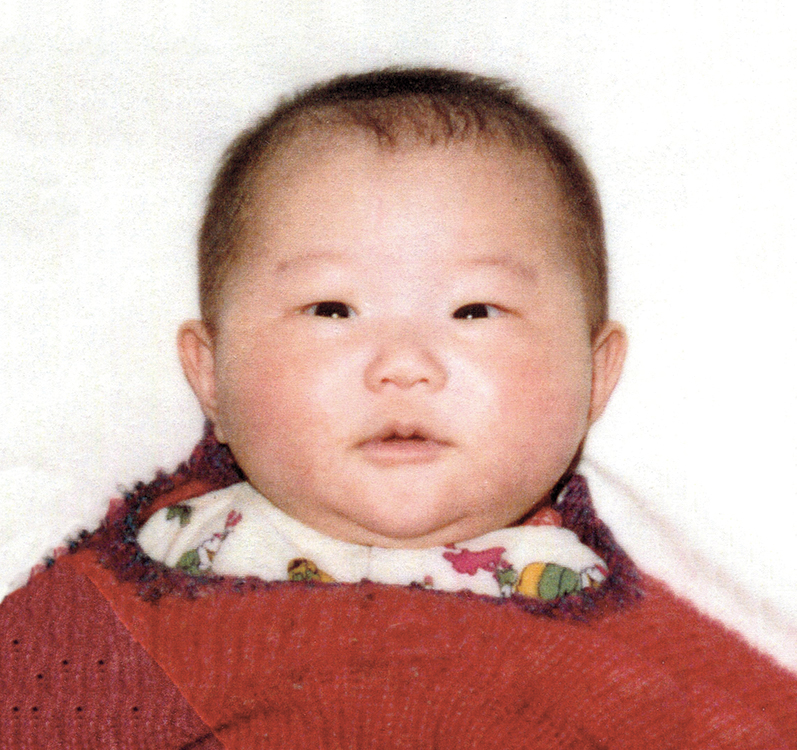

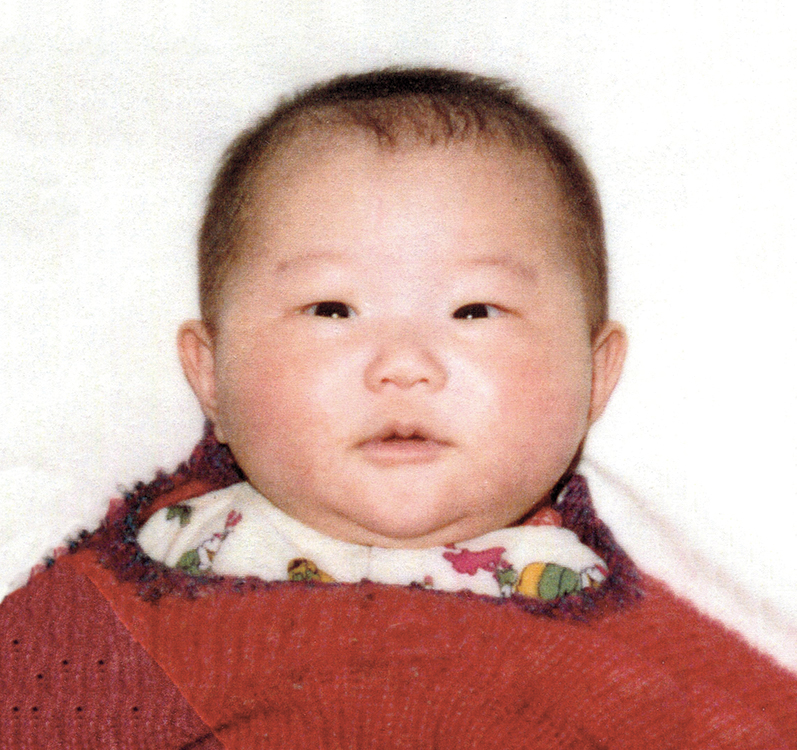

Staff at the orphanage named this baby Chang Yulu. (They gave the surname Chang to all of the children there; Yulu became her given name.) Nine months later, her caregiver placed Yulu in my arms at the orphanage. From the start, I called her Maya. In fact, I’d started calling her Maya as soon as information about her and a photo of her in a tattered, thin red sweater (below) had arrived from China after the two of us were matched to be a family. When I finally wrote her name and mine on the adoption papers in Changzhou, then again in Nanjing, the provincial capital, Maya Xia Ludtke became my only child.

A week later, we flew home to Cambridge, Mass., where we slipped into our family routines. It was just the two of us. I’d gotten married when I was 27, but I’d been divorced at 31. By the time I was in my 40s, I was the archetypal career woman, single, childless, accomplished, and wanting to be a mom, even if I had to become one on my own. Just after I turned 46, that’s exactly what I did.

The story I wrote in 1997 for Wellesley magazine after Maya was settled with me ended with these words: “… when Maya and I returned to our home in Cambridge, Mass., our journey as a family was just beginning.”

Our journey goes on, still just the two of us, as it’s always been. Last August, Maya, about to turn 19, wheeled suitcases out of the bedroom where I had set up her crib 18 years before. I drove her to Wellesley College. Now her bedroom is on the second floor of Pomeroy, and she is a member of the class of 2019.

Back home, I am reconfiguring my life to fit an empty nest.

Maya tugs on her mother’s heart at a baby shower in 1997.

Seven-year-old Maya and Melissa in the market in Xiaxi on their trip to China in 2004.

On her first day in Xiaxi, curious village women invited Maya to a home. Neighbor girls combed her hair.

Maya and Jennie (second and third from right) with girls in their adoption group (who came home from China together as babies) in the summer of 2012.

I figured the pathway through adolescence would be tougher for Maya than for most of her high-school friends. She was, after all, the Chinese-born daughter of an unmarried Caucasian mother, and for many adoptees, the teen years can be emotionally fraught as they carve their self-identity. But those adolescent years weren’t the bumpy ride that I anticipated. As Maya blew out candles on her birthday cake when she turned 16, I made a wish of my own for her. A few weeks later, I offered that wish as a suggestion to her. Would she like to go back to the town where she was found and get to know girls her age who grew up there? I sensed these girls might help Maya to find in Xiaxi Town some vital missing pieces of her Chinese identity.

For some adoptees, the desire to connect with their birth family exerts a strong tug. Maya had expressed no interest in searching for her biological roots, but it turned out that returning to Xiaxi in this way did interest her. I was thrilled. For nearly a decade, I’d felt I owed Maya this kind of an opportunity to make up for what I believed had been my worst day of being her mom.

On that day, I had taken Maya to Xiaxi. She was 7 years old, and we were at the tail end of an exhausting three-week journey in China. This was our first time back since her adoption. Maya told me she wanted to go back to her orphanage, so before flying home, we’d taken a train from Shanghai to Changzhou. There, she walked among rows of cribs and then held a baby. Afterward, the director held a luncheon banquet in honor of Maya and another girl adoptee who was also there that day. That visit went so well that, impulsively, I decided we’d go to Xiaxi the next morning. It wasn’t far away, about 25 kilometers. Why not see the town where she was found, even if her adoption papers did not give us an exact location?

That morning our driver parked the car on the town’s main street. When we walked into the bustling outdoor market—past live chickens, flapping fish, vegetables, and grains—merchants and customers turned to stare at us. We made an odd pair, especially in this rural town where nobody had seen anybody with blond hair and white skin, except on TV. Maya held my hand, and her expression could be read without translation. “I’m scared,” it said.

Some may have been wondering if I’d kidnapped her. A few women approached Maya and tried speaking with her. Maya couldn’t understand, nor did she reply with the usual “Ni hao” (“hello” in Mandarin) she’d politely replied during the rest of our trip in China. She froze and was silent. And the index cards that we had used during the previous weeks—on which Chinese friends had written in Mandarin, “We’re from the U.S. She is my daughter. She doesn’t speak Mandarin.”—were back in our hotel room in Changzhou.

Maya’s grip on my hand tightened, and I knew we had to leave. From the car’s back seat, I asked to return to our hotel. The rest of the day, Maya watched TV in our room without saying a word. Meanwhile, silently, I was scolding myself for being so poorly attuned to my daughter’s feelings. I’d neither prepared her for what we’d encountered, nor had I paused to think about whether she was ready to absorb the range of emotions that such an experience was bound to stir in her. I felt awful.

So I made a promise to myself: Someday I’d help Maya go back to Xiaxi in a way in which she would not feel like such an outsider.

In August 2013, with Maya about to start her senior year of high school, I fulfilled my promise. By then, she had been studying Mandarin since the ninth grade. As a bonus, her friend Jennie, who had lived in a nearby crib in the orphanage and had also been adopted by a Massachusetts family, had asked to come along. She wanted to explore her rural town in the same way. As each spent time with “hometown” girls, the two American adoptees had each other to lean on.

I stayed behind in Changzhou with Jennie’s mother while our daughters went to their rural towns. This was their journey to make, not ours.

In Xiaxi and Xixiashu, Jennie’s hometown, the Chinese girls that Maya and Jennie met were being raised as only children. That wasn’t surprising, since nearly all of the children in this densely populated province grow up without siblings. Unlike most other provinces in China where rural families could try for a son when the first child is a daughter, urban and rural families in Jiangsu Province have been limited to one child, unless they qualify for an exemption, and those are rare.

For several decades, China’s leaders took various approaches to limiting population growth before adopting the one-child policy. When the People’s Republic of China was born in 1949, its founder, Mao Zedong, wanted families to have many children, as most did. But that view had changed by the 1970s, when family-planning slogans like “later, longer, fewer” (encouraging couples to marry later, space their births, and have fewer children) and “one is not few” galvanized a sharp drop-off in family size. China’s fertility rate fell from 5.8 births per woman in 1970 to 2.7 by 1978. Still, in 1979, China’s new leaders linked ambitious goals for economic growth to enforcement of birth planning and sent word out to its citizens to “encourage one, prohibit three.” The one-child policy was born. Then, on Oct. 29, 2015, the Chinese government dropped its one-child limit, enabling urban families to have two children. Most rural families have been able to have two children, if their first child was a girl; now the gender of a rural family’s first child will not be the determinative factor in family size.

—M.L.

The “hometown” Chinese girls showed the Americans what their lives are like, and then they quizzed Maya and Jennie about their experiences in the United States. Topics of their conversations ranged from favorite pop songs to how strict their parents are, from what they want to do for work to when they will be married and to whom. The Chinese girls were a lot more certain about the latter topic, given the pressure on a rural daughter to be a wife by the age of 25.

Since all the girls spent most of their waking hours in school, they talked most about learning. The Chinese girls defined learning as what their teachers tell them and what tests require them to know. When Maya and Jennie told them about the learning they do in activities away from the classroom—environmental activism, anti-prejudice initiatives, fashion shows to raise awareness and funds for victims of domestic violence, to name a few—their new friends were astonished. For starters, they had a hard time believing American high-school students get involved in such issues, and even if they did, the Chinese girls didn’t count these experiences as learning.

“At first, I was kind of mad, because all they were saying is ‘All we do is study and you guys get to do other things,’” Maya said, in digesting what she’d heard. “But then I got to where I know this is just a difference. … But it feels kind of sad to me because the only way their smarts are measured is through tests. It just made me realize that yes, these girls are super-intelligent in their schoolwork, but when it comes to thinking about things like leadership or looking at causes in the world, this isn’t encouraged. … I know they say that I am a Xiaxi girl, but our minds think so differently that we are not connected in that way. We are connected through looks and our origins, but the ways we have grown up is so different that it can be hard to connect.”

“Earlier in our time together, I remember saying I didn’t like it when people would say I am Chinese on the outside and American on the inside,” Maya said, as she approached the end of her visit in Xiaxi. “But I’m understanding where that is coming from, and now I am thinking about how differently I think. I don’t know if it is saying you are not one or the other, but it is interesting to realize how different our ideas are. Some we do agree on.”

As I arranged for Maya and Jennie to meet Chinese girls their age in Xiaxi and Xixiashu, it hit me how rare their visits would be. I couldn’t learn of others like them. The journalist in me saw potential value in what these American and Chinese girls could share. Born in the same place, raised 12 time zones apart, they’d navigate across the cultural divides of their upbringings to find common ground in their lives. I hired a bilingual video crew to be with them, and we captured the girls’ cross-cultural encounters and conversations on video. Now their stories are being shared digitally in a project called Touching Home in China: In Search of Missing Girlhoods. So far, four digital iBooks in a series of six have been published, and the remainder will be out by the spring of 2016. They include video, interactive graphics (for example, a timeline of the development of China’s population policy), slideshows and galleries, and audio-enhanced documents. The stories also appear on the project’s website, Touchinghomeinchina.com. By the fall of 2016, an original curriculum will be available for classrooms using the Touching Home in China material.

—M.L.

Being back in their “hometowns” helped Maya and Jennie fit new pieces into the puzzle of their dual identities. The trees and flowers harvested in Xiaxi connected Maya to the passion she feels about protecting the earth.

The girls discovered parts of their Chinese selves that in the United States aren’t as readily seen or as easily understood. For the first time in their lives, they spent entire days only with people who look like them. They’d been to Chinatown in Boston and other cities, but usually in and out quickly with their moms or Caucasian classmates. This was different.

In the city of Changzhou, Maya and Jennie experienced this new reality while shopping. Surrounded by people who looked like them, they were instantly pegged as foreigners when they spoke. This provoked curiosity about who they were. “We’d say we are from America, and they’d be giving us looks like ‘What are you trying to do, make fun of us or something?’” Maya told Jennie’s mom and me when they returned from shopping.

“I don’t think they understood we are Chinese, but we live in America,” Jennie added. “Or that our parents could be American,” Maya chimed in. Few in rural China know that tens of thousands of Chinese girls are growing up overseas as the daughters of Caucasian families. “It’s hard to explain, and a lot harder without our parents because they give away that we are different in that sense,” Maya said.

Back in the U.S., Maya wrote her essay for college admission about being in Xiaxi. “I was overwhelmed by simultaneous feelings of deep connection and unbridgeable distance. As we struggled to narrow the chasms created by language and culture, I found familiarity in their faces and the trees enveloping us,” she wrote. (To read the full essay, see “The Trip Home,” below.)

Being Maya’s mom on this trip “home” felt just right to me. We’d eat breakfast together before she went to Xiaxi, leaving me in Changzhou. At dinner, she rarely talked about her day. But back in my room, after dinner, I’d watch a video of the girls’ day. While setting up the trip, I had sensed that the girls’ cross-cultural encounters might yield valuable stories, so I arranged for a bilingual team of videographers to capture them. (See “Cross-Cultural Learning,” above.)

There came a moment about two weeks into Maya’s time in Xiaxi when I knew my wish for her had come true. She’d left extra early one morning to meet one of her new friends, Mengping. That night, as the video played on the large TV set in my hotel room, I saw Maya strolling with Mengping and her mother in the same marketplace that she and I had left so abruptly when she was 7 years old. Only this time, she was smiling and laughing, greeting people she knew, and chatting with merchants. Except for the camera she had looped around her neck—and the photos she kept taking—she looked every bit the village girl.

I cried. Only this time, they were tears of joy.

Maya Ludtke ’19 wrote about her experiences in Xiaxi for her college admission essay.

The first nine months of my life are a mystery. A tiny jade bracelet and a photograph of an inexplicably circular face on top of a torn red sweater make up my memory album. A few stapled pages of ambiguous papers constitute my birth record. I do know that I was found in Xiaxi, a farming town of flowers and trees. Though I was nervous about shattering the stable but fragile image I had created in my mind about those nine months, this past August I went to Xiaxi and began to crack through that tableau and experience what my life could have been.

There, I met the girls I could have grown up with, and with them visited the places where I would have spent each day. I was overwhelmed by simultaneous feelings of deep connection and unbridgeable distance. As we struggled to narrow the chasms created by language and culture, I found familiarity in their faces and the trees enveloping us.

“So, what are you?” the girls asked me. “You look Chinese on the outside, but you are American on the inside.” At first, I detested this description. If the substance of my being is not Chinese, I might as well be white. Once content with describing myself as “Chinese-American,” now I was hit with its vagueness. Where do I belong between being Chinese and becoming American? In some ways, my new friends were right; our many fragmented conversations during the three weeks we were together affirmed the differences in how our minds had developed to perceive the world.

“You are so lucky, you have no discipline, easy school, and freedom,” the Xiaxi girls would say with certainty and envy. “All we get to do is study.”

I felt guilty about my “luck” and the truth in their words. Still, their idealistic views about America and the ease of my life perplexed me. They had quickly dismissed my out-of-school activities and community service as lacking real learning. Yet, soon I realized how their understanding of “smart” contrasts with mine. Being smart is the high ranking a teacher gives them; studying is their only way of getting there. These tight borders command their childhood.

I permeated those borders as we talked about growing up, gender roles, equality, and relationships. No one before me had given them the space to talk about such topics. As a girl born in Xiaxi and living in America, I was the most foreign person the girls had ever met. They had never come in contact with anyone who looked different than they do. When I told them about the many friends I have who look different than I do, they were astonished. Being with them gave me deeper appreciation for the diversity that my life in America gives me.

For those I met in Xiaxi, family is blood and ancestry. “You do not know your real parents?” strangers would ask me soon after we met, sympathetic and eager to help me find mine. “When is your birthday? What orphanage were you from?” To me, their words “real mother” sit heavy in my mind. Even if I’d spoken their dialect fluently, I am not sure I could have explained.

I have a real mother, who raised me and loves me. My biological family might not be who I romanticized them to be, and finding such strangers would not instantly conjure love. Instead, it was in the welcoming care that countless strangers showed me—in placing watermelon slices in both of my hands, pulling a comb through my hair, and attempting to cool me in 110-degree heat—that helped me find home in Xiaxi, and that was enough.

—Maya Ludtke ’19

Melissa Ludtke ’73 is the co-producer of the multimedia project Touching Home in China: In Search of Missing Girlhoods. She’s a veteran journalist who worked at Sports Illustrated, CBS News, Time, and the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University. She is the author of On Our Own: Unmarried Motherhood in America.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.