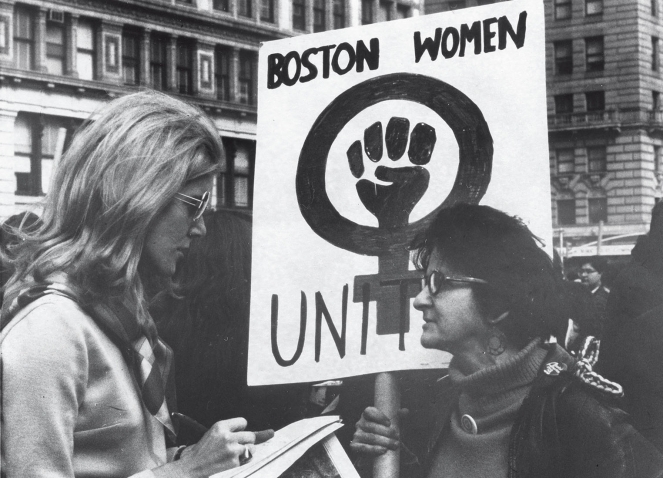

Together, Wellesley’s broadcast pioneers have served the public for decades, providing hard-hitting journalism from political convention floors and campaign planes, interviewing world leaders, and anchoring national news programs. They have won awards and written books. But even after they got in the door, the industry didn’t change overnight. They continued to struggle for equality for decades. And it would be even longer before others—including women of color—got their shot.

When Lynn Sherr was about 9 years old, she published her first edition of the Sherr Family News. It involved painstakingly picking up tiny rubber letters with long, skinny tweezers, arranging them, and then inking and printing blocks of copy. It was such a painful, “ridiculous” process that it also became the only edition of her family’s paper. “But I loved it,” she says. “I absolutely loved it.”

Early on, she “understood the magic” of telling stories and getting the answers to the many questions she had. “I didn’t know how I was going to get there,” she says of her decision to become a journalist, “but it never occurred to me I wouldn’t get there.”

At Wellesley, she majored in Greek and joined the Wellesley News, where she and her classmates “committed what I would consider serious journalism.”

“We were forever tilting against the administration and trying to make things happen, and I loved it,” she says.

After her junior year, she had a summer job lined up in the Associated Press news library but ended up winning the Mademoiselle guest editor contest, which gave her several months working on the August issue of the magazine. Even though she didn’t really want to cover fashion, she found the New York publishing world incredibly exciting.

After graduation in 1963, Sherr barreled out into the real world, determined to find a permanent job in news. She moved to New York, sent out résumés cold, and doggedly followed up to try to get in the door.

She would eventually spend more than three decades with ABC News, as a national correspondent and a correspondent for 20/20. She covered NASA space shuttle missions, women’s issues, national politics, and much more. Sherr won an Emmy Award for her coverage of the 1980 election, as well as a George Foster Peabody Award and a Gracie Award, among others.

But that first summer after Wellesley, she hit a brick wall. Hard.

“Every single male, white newspaper editor in New York basically said to me, we don’t hire girls,” she says. “It’s just the way things were. They didn’t want us, certainly not right out of college.”

She saw men just out of college hired as reporters. The women, meanwhile, were hired to be researchers or to work at the clip desk—cutting out articles and putting them in folders. “This is the way the world was then,” she says. There was no thought of shattering a glass ceiling; she says she wasn’t even expected to look over the pile of folders on her desk.

But Sherr kept at it, even as she realized how much she was swimming upstream. “I was directed at a time to go somewhere where they didn’t want me,” she says, “and I never let it stop me.”

She took a job at Condé Nast, the parent company of Mademoiselle, the only place she could get paid for the first year and a half. Meanwhile, she constantly browsed the (then-segregated) women’s help wanted ads, looking for something else.

She eventually made her way back to the Associated Press, where she stayed for seven years and worked her way up to feature writer. By the 1970s, the working world was starting to change. But there were still moments when she had to push through walls. While at the AP, she was offered a job as the new women’s page editor, which she declined. She didn’t believe the AP should have a separate page for women’s issues and was offended at the very idea.

“I said, with a boldness that no 20 whatever-year-old should have: ‘No, I don’t want that job,’” she says. “‘You don’t have men who are wanting to be the women’s editor.’”

“When I think about it now, I can’t believe I really had the guts to say that … ,” she says. “I put on some boldness I think I didn’t really have, but it was a great time to do it.”

Diane Sawyer ’67 with co-anchor Charles Kuralt on the set of CBS News’ Morning in 1981 CBS/Getty Images

You wouldn’t know it watching her on ABC, but Diane Sawyer describes the student who entered Wellesley in the early 1960s from Louisville, Ky., as shy and introverted.

“I was always by Lake Waban having an identity crisis of some kind,” she says.

But over her four years at the College, she and her classmates started to believe they were going to go out to change the world for the better.

“I just still look back at the miracle of all those women with all that intelligence and all of that sense of possibility,” she says.

After graduation, she started her TV career in a tiny local market back in Louisville—as a “weather girl,” as they were called then.

There was one problem. “I was not made to do the weather,” Sawyer says. She had trouble paying attention and seeing the West Coast on the map because she was nearsighted. “It was a lot of hilarities, as I see it, looking back.” She really just wanted to report the news.

Sawyer doesn’t describe the bias in hiring that many of her contemporaries do. Instead, she had an “astonishing” stroke of luck when her boss at that station let her do the news. “He so believed in everybody in his tiny newsroom,” she says. “He treated us as if we were working for the BBC—as if we were the most important news organization of any day, no matter what we were covering. And so I really felt his encouragement.”

In 1970, she moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a press aide for the Nixon White House and later went to CBS News as a political correspondent. She made history when she became the first female correspondent on 60 Minutes. She joined ABC News in the late 1980s and has been there ever since. For five years, Sawyer was anchor of ABC World News and over her career there has interviewed world leaders including Fidel Castro, Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush, and covered nearly every major world news event. Her journalism has been recognized with Emmys, duPonts, and Peabodys, and she has been inducted into the Television Academy Hall of Fame.

Sawyer says Wellesley solidified her sense of curiosity—and her desire to tell the stories of people who are changing the world.

“I find it hard to do a story that just presents the problem,” she says, “and doesn’t look for the people who believe that there could be a new dawn of a new day.”

Linda Cozby Wertheimer ’65 in her office at NPR headquarters in Washington, D.C., in 1992 Photo by Jerome Liebling/Getty Images

One day as a teenager, Linda Wertheimer was at home in Carlsbad, N.M., a small mining town, sitting in her dad’s recliner while her mother ironed. NBC reporter Pauline Frederick came on her TV. “She was on the steps of the UN, and she explained that the Russian tanks were rolling into Hungary,” Wertheimer recalls. It was the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and Wertheimer says she didn’t know anything about Hungary or tanks. But she exclaimed to her mother: “That’s a woman!”

Her mother replied, “Very good, Linda.” She didn’t consider it profound, but to Wertheimer it was. “It was like a giant thing that I’ve suddenly realized that women can do that work.”

She decided she really wanted to get a job in news, but she assumed that job would be as someone’s secretary. Until she went to Wellesley.

“Wellesley disabused me of the idea of secretary,” she says. She was stunned by her “dazzling” and smart classmates, and she says Wellesley convinced her that “you may have to work your ass off to do it, but you can do it, whatever it is. You know, you want to become a rocket scientist? Fine. You want to write novels? Fine.”

But, as with Sherr, the transition from the insulation Wellesley provided came fast and hard. “There was a lot of possibility,” Wertheimer says, “and a tremendous amount of disappointment and frustration and fury once you got out.”

She temporarily worked for the BBC after graduation from Wellesley and then went back to New York to look for a job.

She describes one interview with an NBC executive who told her that women were not credible at delivering the news. “You just want[ed] to rise up and fly across the desk and strangle this person,” she says. She didn’t, but after about 20 minutes, she says she “threw a fit,” giving the executive a piece of her mind. She was not hired.

After working for WCBS Radio, she got married and moved to Washington, D.C., where she had to start the tedious and discriminatory job hunt again.

Then, a friend of her husband told her about a new startup in town: National Public Radio. She met with an early founder who was dedicated to creating a network that was smart and grounded in reality, and that meant including women on air.

Wertheimer would go on to spend nearly 50 years at NPR and hugely influence the way the network sounds today. She was the first director of All Things Considered in 1971, hosted the program for 13 years, and provided award-winning coverage of politics and Congress. She was the first woman to anchor network coverage of a presidential nomination and of election night in 1976. Like her Wellesley colleagues in broadcast news, she has won numerous journalism awards, including duPonts and honors from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and American Women in Radio and Television.

NPR paid less than the TV networks, but there was one big advantage: There were fewer people to compete against for opportunity once you were in. “If I … had gone to work for the New York Times,” Wertheimer says, “there would have been a whole slew of great big men I would have [had] to assassinate before I could make any progress.”

It’s an incredibly humble explanation for her tremendous success. She became known for being smart and fast—and for mastering the details of any story she had to cover.

In 1994, the New York Times wrote about Wertheimer, Cokie Roberts, and NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg, crediting the three with “revolutionizing political reporting” and birthing “a new kind of female punditry.” The story referred to “demure Linda, delicately crashing onto the Presidential campaign press bus.”

Despite her reporting successes, Wertheimer had to continue to fight for equal treatment along the way. In addition to being paid less than they may have been at the TV networks, she says the female reporters at NPR had desks in the copier room while the men worked in offices.

She recounts a time on the Ronald Reagan campaign plane where another reporter was intoxicated and crawling all over her. “I went to the … press secretary, and I said, ‘If you don’t get this giant asshole away from me, I am going to throw him out the door while the plane is in the air. I promise you, I’m going to do it.’ ” The female reporters were then put in a separate section on the plane—not exactly a win.

But Wertheimer says Wellesley gave her the backbone to stand up for herself. “It gave me not only the sense that I could do anything and should do anything and would do anything, but that I didn’t have to take crap from anybody. … That was a very big thing in my life.”

Roberts with Maryland Sen. Barbara Mikulski at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1996 Photo by Rebecca Roth/CQ Roll Call/Getty Images

When Cokie Roberts died last September, there were two kinds of tributes. She was recognized for pioneering broadcast journalism and political analysis with her smart reporting that helped America understand the news. But to the people close to her and the millions watching, there was something else. “She made you brave,” Sawyer says, “because telling the truth to each other and about the world was a way of traveling beyond the horizon.”

Sawyer says Roberts was the person she would head straight for in a room— “because there is so much news, so much joy, and so much provocative vitality that you just have to be in there [with her]”.

If there is Washington royalty, Roberts was it. Her mother and father both served in the House of Representatives. That upbringing gave her a deep sense of obligation to help America understand Washington, and she spent decades as a political correspondent, analyst, and anchor, mostly at ABC News and NPR. She was also a best-selling author, writing extraordinary women like Abigail Adams and Dolley Madison back into the history books. She won three Emmys, an Edward R. Murrow Award, and many other honors.

After Wellesley, she got her first job with a television production company run by Wellesley alumnae, and she was soon anchoring a program on the Washington, D.C., NBC station. When Roberts got married and moved to New York, she quit her job and started to look for another one. She experienced much of the discrimination Sherr and Wertheimer recall. It “turned out to be a pretty depressing experience,” she said in a video for Wellesley four years ago. “I heard over and over and over again, ‘We don’t hire women to do that.’”

Filmmaker Nora Ephron ’62, who had lived in her residence hall, connected Roberts with a short-term job, and after a stint reporting abroad, she joined NPR in 1977 and later ABC News.

Among those closest to Roberts was Wertheimer, who had known her since the early days of NPR. They remained very close friends and colleagues until her death. They covered Capitol Hill together, working in a way rarely seen among Hill reporters even today: They split the duties of covering the House and Senate, passing stories and interviews back and forth seamlessly.

It’s another quality Wertheimer attributes, at least in part, to the Wellesley spirit. “She’s never trying to do you in,” Wertheimer says. “Our whole philosophy was, when office politics get scary, when somebody comes in and decides that they really want to have the job you have, you just keep your head down and keep filing, because we’re better than almost anybody, and we can do it.”

Sherr shared election-night duties with Roberts at ABC News. She was often the only woman on set, delivering polling analysis. And then came Roberts, owning congressional races on primary and election nights. “She came over to me on the set and she said, ‘Isn’t it great having two girls on the set?’ And it really was supportive and wonderful,” Sherr says. Many female reporters and editors, especially many at NPR and ABC, shared similar sentiments.

“I think [Roberts] believed, maybe, women would be the ones to save the planet,” Sawyer says.

After Cokie Roberts died, journalists remarked on how an incredibly connected network of women had gotten them through those years of struggle. They have had decades-long collaborative professional and personal friendships with each other and with other women from different organizations.

For decades, female broadcast reporters—from competing organizations—would gather for meals at the political conventions or in Washington to catch up and exchange notes. Sherr remarked that after a while, the men started to lean a little closer to their table, listening for sourcing tidbits.

Wellesley is at the heart of many of those connections.

“Wellesley cured us of the idea that women were not good to other women, that women couldn’t be around other women,” Wertheimer says. “The notion that women were somehow going to attempt to eliminate any other women that were in their immediate vicinity. I think we didn’t have that.”

The real legacy of these alumnae is not the struggle or the discrimination: It’s the bold sense of possibility they held onto despite it. “Don’t let anything stop in your way. Don’t let them define who you are,” Sherr says. “You know who you are and what you can do.”

Amita Parashar Kelly ’06 is a Washington editor at NPR, honored to be walking the path that Wellesley’s pioneers in broadcasting, especially NPR’s “Founding Mothers,” blazed.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.