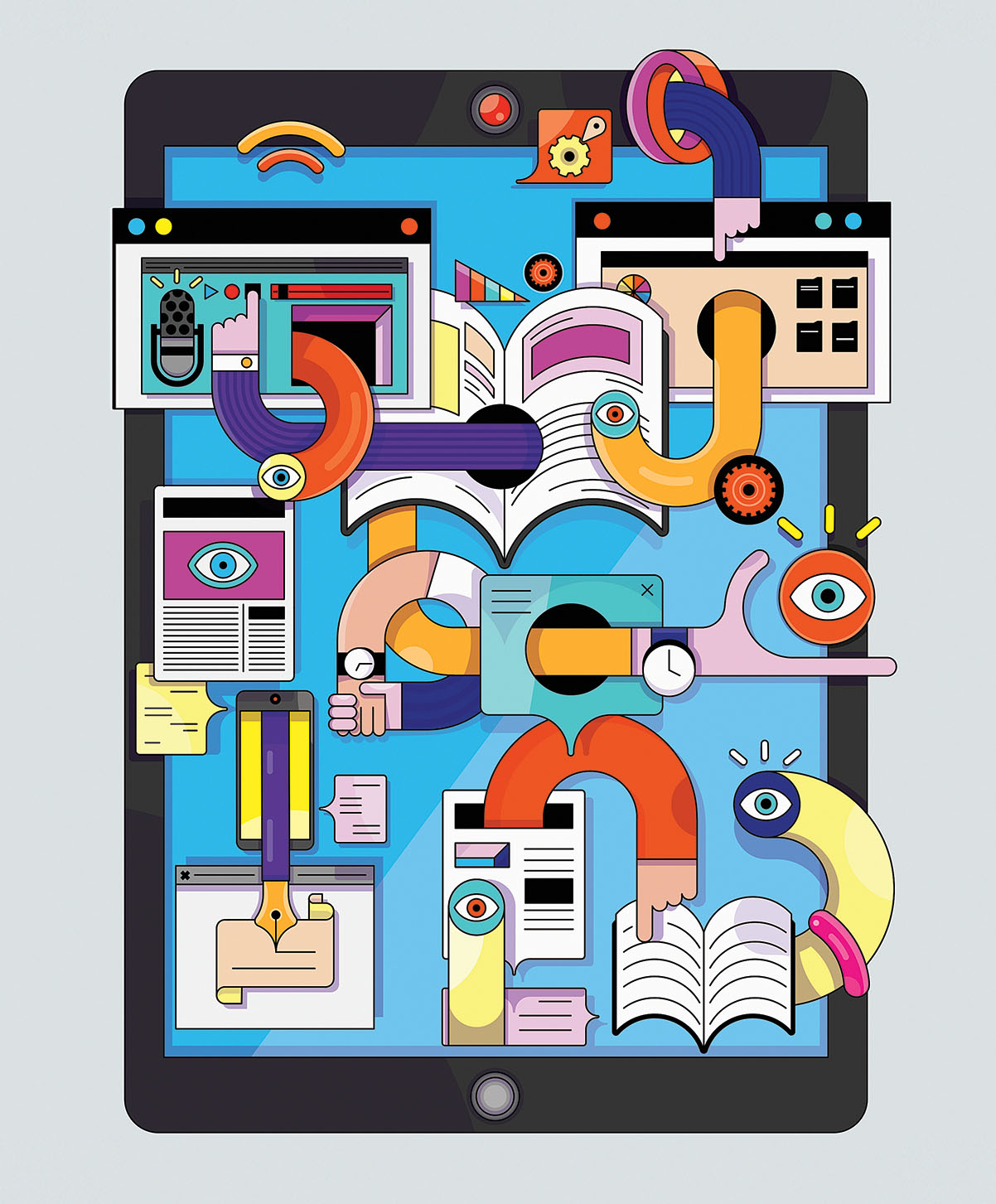

Wellesley professors are experimenting with—and creatively embracing—a wide variety of digital tools to enhance the teaching of disciplines ranging from French to archaeology.

Whether you call it digital scholarship, digital humanities, or blended learning, access to and the use of a range of technologies is changing scholarship and breaking down walls that separate academic disciplines.

In George Eliot’s Middlemarch, published in 1871, classicist and clergyman Edward Casaubon labors in vain over his life’s work, Key to All Mythologies. Pathetically (or tragically, depending on how you feel about the character), he is limited in his ability to synthesize his scholarship by his careless filing practices and his inability to read German.

Imagine if Casaubon had been able to access—and translate—the work of scholars around the world on his iPad. Imagine if he had been able to use tools like MIT’s Annotation Studio, sharing and commenting on manuscripts with other scholars in real time. His Key might have shed its futility and contributed something useful to the world’s store of knowledge.

Whether you call it digital scholarship, digital humanities, or blended learning, access to and the use of a range of technologies is changing scholarship and breaking down walls that separate academic disciplines. And for the past three years at Wellesley, the Andrew W. Mellon Blended Learning Initiative (BLI) has played a role in bringing its new practices into the classroom, from video storytelling and virtual-reality projects to digital mapping, online exhibits, 3-D modeling, podcasts, and blogs.

Does this sound like the simulated reality of The Matrix? Not at all, says Provost Andrew Shennan. The digital humanities are designed to “enhance, not replace, the human and the tactile” in acquiring knowledge.

Digital Humanities Quarterly, the leading peer-reviewed academic journal for this educational approach, defines digital humanities as “a diverse and still-evolving field that encompasses the practice of humanities research in and through information technology, and the exploration of how the humanities may evolve through their engagement with technology, media, and computational methods.”

In the summer of 2014, Wellesley received a three-year, $800,000 grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support exploration of this approach at the College. Evelina Guzauskyte, associate professor of Spanish and the faculty director of the initiative, reports that the BLI has supported 45 faculty members in 21 departments. They have received awards to enhance their teaching, attend and present at national conferences, and bring speakers to campus. At this writing, projects in 55 courses are sustained by the BLI. (Click here to see a gallery of this work.) And from April 6 to 7, Wellesley will host Blended Learning, Digital Humanities, and the Liberal Arts: A Symposium, the capstone event of the initiative.

“Our goals have been to open up a conversation on campus about what blended learning in digital humanities is, what it means for a liberal arts education, and what that means at Wellesley,” Guzauskyte says. “We aimed to support specific work for courses, but also to enable conversations and give us an opportunity to gather collectively to think about our changing roles as teachers and scholars.”

As the BLI concludes, Shennan envisions the project evolving into an approach to teaching that is “woven throughout the entire educational program, integrating blended learning across the whole enterprise.”

‘Our goals have been to enable a conversation on campus about what blended learning in digital humanities is, what it means for a liberal arts education, and what that means at Wellesley.’

—Evelina Guzauskyte, faculty director of the Mellon Blended Learning Initiative

Enlarging the Classroom

A wide range of offerings supported by the BLI have already changed scholarly approaches. For example, students in Associate Professor of French Hélène Bilis’ course, Court, City, Salon: Early Modern Paris—A Digital Humanities Approach, worked jointly with counterparts from Smith College, connecting and working via Skype or FaceTime before meeting in person in Clapp Library’s room 346, a seminar room with computers, projectors, and a smartboard that allow collaborative work.

The Smith students traveled to Wellesley to wrestle with the Comédie-Française Registers Project, a massive, searchable digital archive of 34,000 theatrical performances staged between 1680 and 1791. The Comédie-Française troupe kept detailed records of its box-office receipts for every one of those performances. Scholars from MIT, the Sorbonne, Harvard, and other institutions have extracted the information from the theater’s registers of receipts and compiled it in a database. The platform also offers online tools to investigate the data and render it visually in a variety of charts and graphs. The tools allow scholars to display such things as trends in the popularity of certain plays and playwrights, what contemporary political themes drew the largest audiences, and how attendance spiked when certain actors appeared.

One of the creators of the archive, Jeffrey Ravel, professor of history at MIT, joined Bilis’ class in room 346 this fall. Not a book was in sight as students presented ideas they had developed for interrogating the vast amount of data in the archive and discussed their experiences using the platform. (And by the way, all this work on les humanités numériques was conducted in easy, conversational French.)

In her description of the course, Bilis wrote, “The intersection of traditional scholarship with digital humanities applications will enable students to investigate if, and how, digital humanities methods can broaden, confirm, disprove, or reinterpret dominant analyses of the influential spaces of early modern Paris.”

That’s how it turned out for Withney Barthelemy ’20, a political science major who hopes to study in France as a junior.

“I thought [working with the registers database] was really useful. In normal classes, when you have a research paper, you have to go to the different databases and collect all this data and question your sources, whereas with this, everything was in one place,” she says. “It was interesting to have a chance to poke holes in the database with the creator right there.”

Barthelemy adds, “When it comes to studying French, I care a lot about the people and the culture of the time—not necessarily the statistics. I want to know what life was like, who went to the theater and who didn’t, who had access and who didn’t—the politics of the thing. [The database] didn’t really answer those kinds of questions for me, but we got to pose and answer different questions.”

The Human Touch

Erin Battat, visiting lecturer in the writing program, says a digital humanities approach has enriched her pedagogy.

“Teaching in the writing program has inspired me to think about how we motivate students to write with a purpose, how their writing can translate across disciplines and from the undergraduate experience to their professional lives and lives beyond Wellesley,” she says. “As our world becomes increasingly digital, we need to find ways to integrate writing skills with digital communication.”

Battat welcomed the opportunity to experiment. But she observes that “digital communication has to enhance human interaction rather than replace it.” Accordingly, as she prepared her spring 2018 course, A Nation of Immigrants? American Migration Myths and the Politics of Exclusion, she designed assignments to incorporate human interaction.

“They’re looking at stories about immigration, starting from about the late 19th century, and the capstone project will be a digital story,” Battat says. For that project, students will work exclusively with digital tools, rather than pouring the contents of a conventional research paper into a digital form.

“They’ll need to do the research to tell the story, and they’ll need to interact with people to create the story,” says Battat. “It will also be shown to the class. The process weaves in human interaction throughout the whole.”

‘As our world becomes increasingly digital, we need to find ways to integrate writing skills with digital communication.’

—Erin Battat, visiting lecturer in the writing program

Fieldwork

The BLI also has inspired new ways to conduct research and make it available in class. In his course Bronze Age Greece, Bryan Burns, associate professor of classical studies, teaches the archaeology of early civilization by considering artifacts in their cultural context. His class used Google Maps and mapping and timeline software called Neatline to pinpoint in space and time the distribution in the ancient world of the objects they were studying.

In addition, Kaylie Cox ’18, a student with “mad digital skills,” according to Burns, helped create a digital rendering of the professor’s excavations in Greece, flying a drone to capture images of the site. The resulting maps allow students sitting in a classroom in Wellesley to examine the site in a 3-D rendering.

For his course Home and Away, Justin Armstrong, lecturer in writing and anthropology, takes students to Iceland to explore cultural geography through the lens of anthropology. Increasingly, they use digital tools to do their fieldwork.

“I tell them, ‘You’re doing the same thing that you’re doing in a traditional essay, but you’re just translating it into a different form,’” says Armstrong. “‘You’re making a visual essay that needs to have an argument and references and support and evidence.’”

With the help of research assistant Portia Krichman ’19, Armstrong’s students last summer developed audio-visual essays that included embedded soundscapes, video clips, interactive maps, and still images. The end result was a hybrid of ethnographic writing/research and digital technologies—essentially, an interactive, multimedia essay that documented the individual research projects undertaken by the students in Iceland.

Krichman says a digital essay differs from a conventional research paper in that “there’s a lot more opportunity for the viewer to share the experience of the person writing it. You can have multiple, varied ways of showcasing the information. It feels more like art than an essay.”

More than a Game

Julie Walsh, assistant professor of philosophy, took the blended learning ball and ran with it in her courses.

“In philosophy classes, the main skill we’re trying to teach our students is clear, concise, precise, argumentative writing,” says Walsh, “but it gets a bit dry.” So she asked herself, “How can I meet my objectives for skill and content development with my students, but in a way that’s a little less dry?”

In Introduction to Moral Philosophy, she invited the students to create a game based on the course content, putting the students into teams and introducing them to Twine, open-source software that enables storytelling that includes conditional logic—if this, then what? The BLI provided funding to hire a teaching assistant, a computer-science major who provided support for students as they learned the software. Students chose a moral problem, then guided the game player through a series of choices based on philosophical approaches to solve it.

“One group did the ethics of eating animals,” says Walsh. “Another explored if you’re shipwrecked with a group of people, how to prioritize who should be eaten when the time comes. One group chose to do nepotism—thinking about privileging your family over strangers.”

As with any assignment, the finished product was better for some teams than others, Walsh says. “But it really got them talking with each other about the theories and then figuring out the best way to showcase them.”

Students enjoyed the process. “I had some really positive feedback,” Walsh says. “A senior who was a straight-A student was very worried about doing well, and she hated group work. Afterwards she told me, ‘I can’t believe it, but I think the group assignment was my favorite part of the course.’” Another student told her, well over a year later, that learning the gaming software gave her the confidence to explore computer-science classes.

For another assignment, Walsh used video diary keeping. “I called it a 48-hour confessional. Because philosophy can be so dense, I wanted to use other formats to draw out the content.” She put cards in a hat with the names of four approaches to moral philosophy—utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, and care ethics—on them. Students drew cards and then, for 48 hours, had to live according to the theory and keep a video diary of the experience.

“I hope these approaches showed students that philosophy can be discussed in ways that aren’t text,” says Walsh. “My strategy’s not to give up on teaching writing. We’ll never do that. But why not acknowledge that lots of our students are going to end up working in fields where all their expression will be mediated through technology? Why not dabble in it now? By exploring the digital realm, we’re not abandoning what has worked for millennia. It’s multimodal. There’s no reason we have to choose.”

‘My strategy’s not to give up on teaching writing. We’ll never do that. But why not acknowledge that lots of our students are going to end up working in fields where all their expression will be mediated through technology? Why not dabble in it now?’

—Julie Walsh, assistant professor of philosophy

Assessing the Tools

One of the challenges of a new field is developing rubrics to assess its success. “It’s really tough,” says Walsh. “I don’t know how to grade creativity. But you can grade legibility. You can grade the quality of the audio. You can grade the diversity of ideas. There’s a sense in which we can be objective about certain things. Also, when doing a more creative assignment, what I’m looking for is the buy-in. And if I see that the buy-in is there, even if the final product isn’t perfect, it’s the buy-in that I care about, and the demonstration of the philosophical skills.”

Assessing digital humanities work has another aspect, too, of course. How does this kind of work factor into a faculty member’s tenure portfolio? Institutions have been lacking clear standards to weigh digital scholarship during tenure review.

“This work generally no longer fits within simply pedagogical or research or publication rubrics,” says Guzauskyte. To recognize digital scholarship, several professional institutions and organizations like the Modern Language Association and the American Historical Association have published new guidelines for reviewing work in the digital sphere, and some colleges are publishing their own guidelines. “We are right in the middle of that conversation,” Guzauskyte says.

No Magic Key

Digital humanities offer new and different ways to access and render knowledge—though they may not hold the magic key to all mythologies that George Eliot’s Rev. Causabon spent his life seeking in vain.

Assistant Director of Research Services Laura O’Brien, who worked with BLI faculty to choose and apply digital tools for their classes, puts it this way: “The technology cannot be the driving force.”

She says faculty members often ask her, “‘What tool is going to get my students to communicate in writing in class, in class discussions?’ And the thing is, the tool isn’t the answer. The tool can be part of the way that you encourage something, but finally it’s all about how it’s pedagogically framed within the class, what the communication is, and how that ties to the content.”

Senior Associate Editor Catherine O’Neill Grace is working on a memoir about her childhood in India. Her research for this story has inspired her to try out some digital methods for recapturing her memories.

Senior Associate Editor Catherine O’Neill Grace is working on a memoir about her childhood in India. Her research for this story has inspired her to try out some digital methods for recapturing her memories.