Michele Moody-Adams ’78

In late May 2020, Michele Moody-Adams ’78 went for a walk, hoping to clear her head during a particularly busy season in her life. Instead the Joseph Straus Professor of Political Philosophy and Legal Theory at Columbia, stumbled upon a protest—and the inspiration for her next book.

In late May 2020, Michele Moody-Adams ’78 went for a midday walk through Central Park, hoping to clear her head during a particularly busy season in her life. Michele, the Joseph Straus Professor of Political Philosophy and Legal Theory at Columbia, was serving as chair of the philosophy department, the pandemic was in full swing, and across the nation, political unrest was rising along with the temperature. But instead of finding the peace and quiet she sought, she stumbled upon a protest—and the inspiration for her next book.

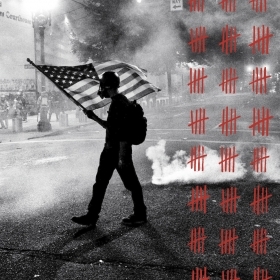

The demonstrators were among the tens of millions who took to the streets protesting the deaths of George Floyd and other Black people at the hands of police officers. But what stood out for Michele was how hopeful they seemed that day, masked and peaceful, “the types of people who had never imagined going to a protest,” she remembers.

“In a time that might have been a source of great anger and despair, these people were finding hope through their involvement in this collective action,” she says. “There was an inspirational character to what they were doing that I thought I needed to be talked about.”

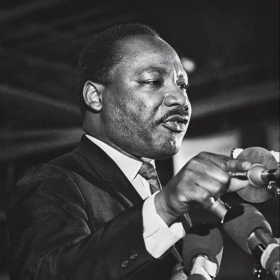

Her insight that day grew into a book that connects the theory of political and moral philosophy to the practice of social justice activism. Making Space for Justice: Social Movements, Collective Imagination, and Political Hope begins with the 19th-century abolitionist movement and continues through #MeToo, traversing historical, geographical, ethnic, and gender lines, and looks closely at movement intellectuals such as Václav Havel, Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Catharine MacKinnon.

“I had a long interest in moral progress and the role of social movements in helping to shape that, but I never thought about what they might be trying to teach us,” she says. “So I asked the question that nobody in political philosophy had ever asked: What would it mean to take social movements seriously? Not just as sources of practical efforts to change the world, but sources of cognitive rational insight about what you want the world to change in order to be better.”

The daughter of public school teachers on Chicago’s South Side, Michele came of age during the Civil Rights and student protest movements of the late 1960s. Although her parents were not the “demonstrating type”—in fact, they made her stay home during the riots that erupted in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention—they supported social change in other ways. She remembers her father bringing home books by Martin Luther King, Jr., “hot off the presses.” Particularly influential was his 1964 book, Why We Can’t Wait. “I just devoured it,” she says. She was not yet 10.

While at Wellesley, Michele became politically active in the movement to end apartheid. She also discovered her vocation in philosophy classes taught by Professor Ifeanyi Menkiti. “Philosophy can be abstract,” she remembers him saying, “but it can also bake a little bread.” It’s a phrase that still resonates with her today.

After graduating, Michele won a Marshall Scholarship to study philosophy at Oxford University, where, during her first week, she met the man who would become her husband, James Eli Adams, now also a professor at Columbia. (They are the parents of an adult daughter.) Back in the U.S., she earned a Ph.D. at Harvard while teaching for four years in Wellesley’s philosophy department, years she recalls as “some of the happiest of my life.”

Now that she has finished her term as department chair at Columbia, she is enjoying some peace and quiet during a year of academic leave. Ever the scholar, she is already thinking of her next project—perhaps a book about the political philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. She finds herself reaching back to her earliest intellectual roots and that copy of Why We Can’t Wait.

“I realized there was so much that I missed,” she says.