Wellesley is undertaking an ambitious plan to reduce its environmental footprint and engage with its beautiful campus in new ways.

Wellesley is undertaking an ambitious plan to reduce its environmental footprint and engage with its beautiful campus in new ways—and has named 2017–18 the Year of Sustainability.

The stewardship of Lake Waban is central to the College’s commitment to sustainability and environmental awareness.

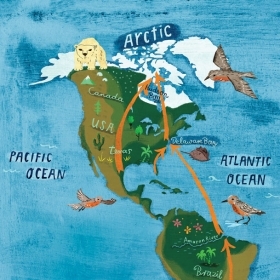

On Sept. 11, conservationist Wendy Judge Paulson ’69 went bird-watching with a gaggle of students, staff, and faculty members. They had a pretty good morning—during an hour’s ramble through Alumnae Valley and alongside Lake Waban, the group spotted some 24 species, including a yellow-rumped warbler, a pied-billed grebe, and a quarreling group of warbling vireos. In the tupelo trees along the winding paths, the watchers spied catbirds, cedar waxwings, and goldfinches. It was a perfect morning to be out in the landscape.

It was not always so. Before 2005, a stroll through this area bordering Lake Waban on the west side of campus took the walker across a crumbling parking lot and past decaying tennis courts, all of which was on top of a brownfield of toxic soil. It’s easy to forget that what is today Alumnae Valley is a built environment, a wetland in which the landscape is configured so that water runoff flowing through it is cleansed before it reaches the lake.

The ambitious restoration project earned a 2006 Award of Excellence by the American Society of Landscape Architects in a competition that included 500 international submissions. In the years since its completion, nature has so abundantly returned to Alumnae Valley that (along with bird-watching) a range of outdoor activities—including identifying plants, finding amphibians, and locating pollinators—was offered as part of the campuswide Sustainability Day on Sept. 11. The day inaugurated the College’s Year of Sustainability as well as the Wendy Judge Paulson ’69 Ecology of Place Initiative.

“The 2017–18 Year of Sustainability will engage students, staff, and faculty in conversations about what sustainability means to us as individuals and as an academic and residential community,” President Paula Johnson wrote to the College community this fall. “Both the Paulson Initiative and the Year of Sustainability will help prepare our students to be active, engaged, and environmentally aware global citizens.”

Photo by Richard Howard

During Sustainability Day on Sept. 11, Wendy Judge Paulson ’69 points out a bird to an attentive student.

Change is Possible

The 2017–18 Year of Sustainability is the brainchild of the Advisory Committee on Environmental Sustainability, a group of faculty, staff, and student representatives who worked with the College to create an ambitious, 10-year plan that stakes Wellesley’s future on sustainability and commits to a dramatic reduction of the College’s environmental footprint. In April 2016, the Wellesley College Board of Trustees approved the plan.

Laura Daignault Gates ’72, chair of the board, was instrumental in moving the plan through the approval process. “Each of us needs to contribute to healing and maintaining our environment,” Gates says. “The College is not exempt. These topics are a necessary part of a relevant 21st-century curriculum.”

As an institution, Wellesley is committed to environmental stewardship as it moves into the future. “We are building new buildings and have asked that sustainable practices be incorporated,” says Gates. “We are investing in new, sustainable energy technologies, not only because of the potential for high returns, but because it aligns with our values. Learning what sustainability means and adapting our behavior is part of making a difference in today’s world.”

Steps on the Road

The goals of the College’s sustainability plan include:

- Reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 37 percent by 2026 and 44 percent by 2036 (from a 2010 baseline);

- Reducing potable water consumption by 50 percent by 2026 (from a 1999 baseline—39 percent was already achieved between 1999 and 2014).

Additional goals include phasing out plastic bags at campus retail operations, making sure that 90 percent of the office paper purchased by the College will have at least 30 percent post-consumer-recycled content, and providing support for faculty across all disciplines—not just the sciences—who want to integrate discussions of sustainability into their courses.

The sustainability committee worked for three years to develop the plan, collaborating with the facilities department and holding campus-wide events to gather input from faculty, staff, and students. Among the plan’s goals for eight separate sectors are:

- Academics: Increase hands-on learning and research opportunities in sustainability and expose incoming students to sustainability at Wellesley.

- Buildings: Address the backlog of deferred maintenance of buildings and their supporting infrastructure and establish protocols for each building for maximum energy efficiency.

- Climate and energy: Install solar arrays on campus that can supply 5 percent of the College’s electricity demand over the course of a year; meter 80 percent of buildings for electricity and other utilities and make the information available for management and decision-making.

- Food and dining: Create a better system for collecting more food-related data and information and increase sustainable food and utensil purchases.

- Landscape and watershed: Improve sustainability of water management, including storm water runoff, and increase metering, measurement, and environmental testing.

- Purchasing and waste: Undertake a systematic review of waste management on campus and report monthly statistics on volumes of waste and recycling, as well as increase the number of administrative offices taking part in a challenge to be sustainable.

- Transportation: Reduce single-occupant personal vehicle use for commuting from 80 percent to 60 percent of trips by 2020 and increase the efficiency of the Wellesley Motor Pool fleet with new purchases and replacements.

- Water: Pursue improvements to the campus’s already high-quality water supply, including the upgrade of the College’s aging water supply infrastructure, which is the source of taste complaints about campus water, and phase out the purchase of bottled water across campus.

Photo by George Grall/Getty Images

A yellow-rumped warbler, one of the species spotted by the bird-watchers.

Focus on Sustainability

Wellesley’s Year of Sustainability is part of the College’s road map to an environmentally responsible future. “I’m nervous and excited,” said Yui Suzuki, associate professor of biological sciences and chair of the Advisory Committee on Environmental Sustainability, as the academic year began. “I don’t think we’ve had a theme year any time in recent history. I don’t know how it’s going to work out—but I do think it’s exciting that we can get the whole campus to think about sustainability. It has to be a grassroots movement at this point.”

Throughout the 2017–18 academic year, sustainability and/or climate change will be a theme, imbuing the annual Douglas, Wilson, and Goldman lectures and monthly faculty talks in the Science Center. Invited speakers will include an advocate for zero-waste living; an expert in sustainable architecture; and an academic working at the intersection of biology and art. A philosophy colloquium will address moral and political issues concerning climate policy.

A behavioral-change campaign will be run in student dorms by eco-reps who will encourage recycling and reduction of waste (see “Reppin’ for the Planet,”), and the sustainability committee will host a competition to encourage student engagement in sustainability-related projects on campus. In addition, the committee has provided faculty with tools, such as reading lists and websites, for integrating sustainability into their teaching, says Suzuki.

Defining the Term

So, what does “sustainability” mean at Wellesley? In 1987, the UN Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” But as Suzuki talked with people around the College, he says he realized that “there was just no clear understanding of what sustainability means. Everyone asks us, what does sustainability mean? And I think this is something that’s very important to define for the College. Each institution needs to come up with its own definition.”

‘To me, sustainability means being committed to using resources responsibly and eliminating waste. Sustainability is not a “bolt-on.” It is integrated into everything we do.’

“To me, sustainability means being committed to using resources responsibly and eliminating waste,” says Dave Chakraborty, assistant vice president for facilities management and planning. “Sustainability is not a ‘bolt-on.’ It is integrated into everything we do. I am elated that the trustees have adopted a sustainability plan. And I am optimistic that we will meet the goals because the trustees, senior administration, and the College community are committed to promoting sustainability. The biggest challenge will be to find the initial investment dollars. We can surmount the challenge, however.”

Chakraborty would like to see Wellesley, which last year was number 75 on the Sierra Club’s “Cool Schools” list, begin to climb up that assessment ladder. The annual list ranks colleges and universities on “green” measures that reflect the broader priorities of the Sierra Club—campus energy use, transportation, and fossil-fuel divestment. “If we all work together, I am sure that we will rank among the finest sustainable colleges in the nation,” he says.

Helping to lead the charge is Rob Lamppa, who joined the College as director of energy and infrastructure and chief sustainability officer in October. An engineer by training, Lamppa brings broad experience in physical-plant operations and improving sustainability performance, honed in his role in sustainability operations at the 935-acre campus of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“Energy use management—from the power plant to the buildings—is the key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing GHG emissions is one of the key goals of the sustainability plan, and Rob’s experience and background will lead us in the right direction,” says Chakraborty.

Varied Views

The advisory committee took a stab at defining sustainability last year in a vision statement: “Sustainability is a multifaceted, complex concept that touches on various issues ranging from climate change and renewable resources to social justice and policy. A major goal of the sustainability year is to bring together a great diversity of perspectives about sustainability and to promote a campus-wide conversation about sustainability. Through this initiative, we hope to engage the College community in vibrant discussions about what sustainability means for Wellesley College and to promote positive behavioral changes that reduce waste, promote recycling, and conserve energy.”

One committee member takes it further: “For me personally, [the definition] is tricky,” says Sarah Barbrow, a science librarian. “A crucial component of the word just means to be maintained over time. … I personally think of sustainability with ‘green’ in my head, but I try to remind myself that the College can’t be green without being financially sustainable.”

What do the students say? Answers vary, but Hazel Wan Hei Leung ’20, a history and political science major from Hong Kong, says, “For me, sustainability comes down to leaving the Earth a better place than you found it—politically, economically, and socially. For me, environmental sustainability is not unconscious of economic ramifications. It has heart.”

As a first-year, Leung became involved with EnAct, the newest student environmental organization, and serves on its executive board. “Our mission basically is to promote environmental action on campus. We’re interested in issues of food justice and engaging with the administration about environmental issues,” she says.

“We’re excited about the Year of Sustainability and working with a lot of environmentally minded people on campus. I think people are ready to have the conversation. It’s very timely in the political era we’re living in. We support environmental justice—not just on the campus, but also in the world. It doesn’t matter where you live; it’s global. That’s the scariest part, but the most uplifting part—that sense of a common cause.”

Suzuki, who believes sustainability is “a way of living, a way of life,” says, “We hope by the end of the year to have a concrete set of definitions, or at least some guiding principles. The hope is, the students will take some of the ways of thinking about sustainability and the behavioral change that comes with it with them beyond the College.”

‘We are the stewards of these spaces and the life that fills them.’

—President Paula Johnson

Stewards of Place

Those working on sustainability at Wellesley see a connection between on-campus practices and broader environmental challenges. “Taking action here is consistent with our commitment to ‘minister unto,’” the Wellesley College Strategic Sustainability Plan states.

In that spirit, running concurrently with the Year of Sustainability—and integrally linked to it—is the inaugural year of the Paulson Ecology of Place Initiative.

This program, made possible by a generous gift from Wendy Judge Paulson ’69, seeks to use the beauty, diversity, and history of the landscape to teach environmental literacy and inspire environmental action. It will intentionally connect all Wellesley students to place, to the flora and fauna with which they share their four-year home and the natural rhythms of life outdoors.

The initiative will include hands-on management of key ecosystems on campus, building a knowledge base through case studies. These efforts will enable students to get to know and understand the campus biological communities—such as Alumnae Valley, the Science Center meadows, Lake Waban/Paintshop Pond, Paramecium Pond, the Edible Ecosystem Teaching Garden, and the Bog Garden—by taking care of them. It will also involve activities in the arts and humanities, with writing classes using Wellesley’s setting as a journaling or poetic muse, dance performances inspired by the landscape, plein air painting, photography, and more.

For Kristina Niovi Jones, director of the Wellesley College Botanic Gardens and adjunct assistant professor of biological sciences, environmental literacy is a core skill students should acquire, on a par with public speaking. She sees intrinsic scientific value in the acres on campus that she calls “a living laboratory.” In the long term, Jones says, “reversing the reckless decline of ecosystem health and biodiversity globally is the ultimate goal, as graduates take their love of nature with them when they leave Wellesley.”

That love of nature is central to the whole community’s experience of the campus—not just students. Alumnae, faculty and staff, neighbors—and the president—cultivate it as well. At the evening event launching both the Paulson Ecology of Place Initiative and the College’s Year of Sustainability, President Johnson recalled that when she was exploring the arboretum with Jones, she “took a moment to listen to some birdsong.”

“We are the stewards of these spaces and the life that fills them,” Johnson said.

[supporting-images]

An Environmental Ethic

Spearheading the Paulson Ecology of Place Initiative is director Suzanne Langridge, who joined Wellesley this summer from the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University.

At her interview for the directorship, Langridge brought along a hands-on ecology activity in a bag of twigs, leaves, and mosses, “just some things from different places in California that were special to me,” she says. “I did a little activity with everybody, asking them to close their eyes, and just use their senses to think about, what is this? What does it remind me of? What does it make me think about? Then they got to open their eyes. It was fun, because [the material] wasn’t from here, and there were a lot of ecologists in the room trying to figure out, what is this thing?”

Not surprisingly, Langridge got the job. “I see ‘ecology of place’ as the intersection between nature and culture,” she says. “How do we bring those things together in a way that students can build an environmental ethic?

“This position really is about trying to connect students to the landscape here in Wellesley. Not just bringing biology students out for a field class, but really across the board, asking, how can we get students to connect to this landscape.”

Langridge quickly noticed how passionate alumnae are about the Wellesley campus. “Alumnae come back and talk about the whole idea and philosophy behind making this campus, building the landscape in a way that really allows connection to nature to happen as students are walking from class to class. There’s already a strong foundation, an underlying belief, that that’s what the campus is about.”

With a Ph.D. in environmental studies and ecology and evolutionary biology, Langridge has taught courses in animal ecology and conservation, ecosystem restoration science and policy, and insect ecology. She hopes to work right away with faculty on how they can make more use of the campus, and how she can help with that. “At some point, I’d especially love to do some team teaching across disciplines,” she says. “But for now, I will be doing a lot of listening to students.”

Among the students Langridge is likely to listen to is Riley Rettig ’20, who went bird-watching with Wendy Paulson on Sept. 11. “All the numbers and graphs about reducing our carbon footprint are critically important,” says Rettig, “but if people aren’t out in nature, it’s not going to make much difference to them. We need to cultivate an environmental ethic on this campus.”

Read more about the College’s sustainability plan here.

Senior associate editor Catherine O’Neill Grace was thrilled to see a Baltimore Oriole one morning when she was walking through Alumnae Valley. As the Year of Sustainability gets underway, she’s making an effort to reduce her use of paper in the magazine office.

Senior associate editor Catherine O’Neill Grace was thrilled to see a Baltimore Oriole one morning when she was walking through Alumnae Valley. As the Year of Sustainability gets underway, she’s making an effort to reduce her use of paper in the magazine office.