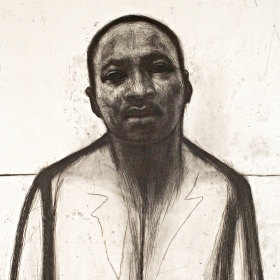

Wakemia, large ceremonial spoons like the one pictured below, played a vital role in the spiritual and cultural life of the Dan peoples in Ivory Coast and Liberia in the 19th to early 20th centuries.

The wakemia was a sacred object given to the woman who was considered the most successful farmer, manager, and host in the village. She assumed responsibility for organizing feasts, and so became known as a wa ke de, or “feasts acting woman.” The honor was bestowed on her by the preceding wa ke de, but the recipient also needed to have a vision in which the spoon spirit accepted her and conferred the right to be the wa ke de. The spoon hung in a place of honor in the woman’s hut, and on feast days it was paraded through the village, its bowl filled with rice, peanuts, or coins to symbolize bounty and the role of women as sources of food and life. Later, when a new wa ke de emerged, the spoon would be passed into the next woman’s keeping.

“Dan women related to the spirit world through the wakemia in a corresponding way that men did to masks,” says Amanda Gilvin, an assistant curator at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College. “This spoon was the vehicle for a spirit to make itself known to the community.”

Wakemia vary in shape and size (ranging from one to two feet tall), but they all depict women’s bodies, and the bowls represent the rounded shape of pregnant bellies. They are beautifully carved, and often include intricate patterns that echo the scarification on women’s skin that was regarded as a mark of beauty. The handles most often depict human heads, but they can also represent animal heads or human legs and hands. “Their appearance references the importance of women’s labor and the beauty of their bodies,” Gilvin says.

As is true of many African ceremonial objects that have come into the hands of Western collectors, the origins of this wakemia are obscure before it came to the J.J. Klejman Gallery in New York. The Klejmans specialized in African art, and their gifts, and those of their daughter, Susanne Klejman Bennet ’59, make up a large part of the Davis’s African collection.

This wakemia is displayed for the first time in many years, along with approximately 85 other works of African art, in the newly reinstalled permanent collection at the Davis, which reopened in September. A full story about the reinstallation will appear in an upcoming issue of the magazine.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.