I had never seen a winter wren until yesterday, when I made the introductory tour of Hedgebrook’s woods with Barton. An excellent naturalist, he reeled off the names of trees and shrubs and mushrooms until I yearned for paper and pencil to write and sketch this abundance of natural history detail into memory.

In the midst of his litany, a movement, not color, caught my eye, a small something that materialized into a bird that moved briskly, through and under fallen branches, prodding and poking at dead leaves and twigs. I tiptoed after it, [expecting it to] disappear. Instead it bustled along, unconcerned by my scrutiny, too busy to bother with observers, listing and sifting and jabbing for insects in the debris that accrues on a northwestern forest floor. Bustly little creature, rotund of body, short-tailed, self-contained. I whispered “wren” without exactly knowing why, then added “winter?” That unsuspected identity must have been drawn from a pattern in some mental file drawer listing the combined characteristics of small, engrossed ground feeder with dark feathers, winter active.

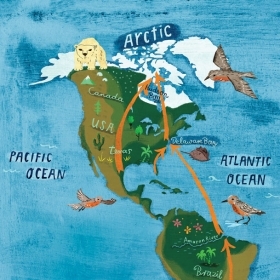

Without a name I can learn nothing about the current object of my affection. It greatly satisfies something in my untidy nature to know that I watched Troglodytes troglodytes, and to know its name came from the Greek meaning for a creeper into holes or a cave dweller. And to find out that while there are nine species of wrens in North America, winter wrens are the only wren species in Europe. In many parts of North America, they are winter-long singing members of the forest—Thoreau heard its “incessant lisping tinkle” in the mountains of New Hampshire.

A name also defines what is not as well as what is. A wren is not a red-winged blackbird and the why is as interesting as the fact. Now I can look up wrens in general and this one in particular. Maybe I’ll even find one of those captivating connections that so delight devotees of natural history, feel a delectable sense of satisfaction, smile out loud, feel better about the hour.

Unfamiliar as these woods were, they became on the instant “home.” A place where I knew somebody’s name, not as something to check off on a trophy list but a handle on finding something out about it. Yes, I recognized the hallmark hemlock and red cedar, Douglas fir and bigleaf maple because Susan, my eldest daughter who lives on Whidbey Island, taught me. But it was that self-absorbed, officiously energetic little wren that gave me welcome. Given that I scarcely knew a wren from a wrench from a wench from a winch thirty years ago, when I started writing, I draw enormous pleasure from what has been added to my life.

Answering the question “What is that?” means that, over time, one builds a vocabulary of names, an activity which may sound about as exciting as watching the pudding set. But not to this taxonomical devotee. I believe in knowing the names of things, the assigning of which is a human necessity. Taxonomy allows me to access a massive body of knowledge. A name is a pathway to getting acquainted. Only then can I find out how a Douglas fir responds to the wind storm of the summer hail, how it grows and how it whispers, how it gets along in the world, how it values its habitat. … I used to define the space designated in my mind as “home” by the name of my town, my telephone number, and my street address. But in recent years I have begun to feel that there are more important designators for me and that I need to learn them: the native trees, the native wildflowers—the first in spring, the last in autumn—wherever I walk. A constant flow of questions results: I know that shrub growing along the path, and what its beneficial uses are, but not what spider festoons its branches. Not the mushrooms that spring up unbidden in the grass. I do know what the name of the small, splayed-open ivory lilies nesting close to the ground in early spring is, and what bird carols me awake in the morning, but I don’t know what the migration patterns are of the birds that match the seasons. That knowledge may be as or more important than my numerical existence.

I believe that knowledge of one’s neighborhood, of the plants and animals and insects and rocks (and everything else I’ve left out) that share our space, ought to be part of everyone’s lexicon of place. Surely it’s not asking too much for each of us to know ten native plants, ten stars by name, ten six- and eight-legged crawlers and hoppers? … [I]f you don’t know home, how can you care for where you live?

Ann Haymond Zwinger ’46 spent her childhood growing up along the White River in Muncie, Ind., which inspired her storied career as a naturalist and author. Zwinger, who majored in art history, wrote and illustrated some 20 books on the natural history of North America. She died in 2014.

From Shaped by Wind & Water: Reflections of a Naturalist by Ann Haymond Zwinger (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions 2000) © 2000 by Ann Haymond Zwinger. Reprinted with permission from Milkweed Editions. milkweed.org

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.