This summer and fall, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Wellesley faced a daunting task: develop a testing program that would allow students to return to campus while keeping the Wellesley community safe.

“A big part of being a student at Wellesley is being on campus, having in-person contact with our faculty, so if we could do it safely, we wanted to try to bring students back,” says Karen Petrulakis, the College’s general counsel, who chairs a team of staff members focused on securing the health and safety of the campus community.

The story of Wellesley’s COVID-19 testing program started in the spring, when President Paula Johnson was asked by Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker to participate in a higher education working group focused on reopening campuses. As she and the leaders of other colleges and universities discussed how to bring students back safely, they quickly determined that frequent testing would be key—yet such testing was pricey and in short supply.

Johnson became chair of the Massachusetts Higher Education Testing Group, which began exploring testing options. Enter the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. In mid-March, the Broad successfully converted a genomics lab into a high-throughput COVID-19 test processing center. The group “asked whether the Broad’s capacity might be able to assist higher education,” recalls Broad president and founding director Eric Lander. For him, the answer was obvious: “I didn’t think we had a choice—our whole mission is public service, we’re a nonprofit institution, and we wanted to serve these institutions.”

‘There has been a united focus on the common good: How do we serve students? How do we keep our community safe? How do we communicate our approaches to health and safety?’

—President Paula Johnson

In total, 108 colleges and universities throughout New England collaborated with the Broad and each other in developing their own testing plans. “It has been remarkable to see the broader higher education community—and the scientific and medical ecosystem—pulling together,” Johnson says. “There has been a united focus on the common good: How do we serve students? How do we keep our community safe? How do we communicate our approaches to health and safety?”

Based on available classroom and residence hall space, the College invited first-years and sophomores to live on campus this fall. They will swap with juniors and seniors for the spring. Students self-quarantined for two weeks before coming to campus. Those from the states with a high incidence of COVID-19 identified in the Massachusetts travel orders took an at-home test before traveling. Arriving early, they quarantined in a hotel near campus until they had two negative tests, and could move to their residence halls. Students from other locations arrived in waves and quarantined in their rooms until they had received two negative tests—at which point they could venture out, wearing masks and observing social distancing.

All students were tested every two to three days well into September, and as of mid-October, students were still being tested twice a week. Testing sites are in the Davis Parking Garage and at the College Club, and the process is largely contactless: Students check in via Wellesley OneCard and self-swab their nostrils under the supervision of a health-care professional, who can assist using rubber gloves built into a plexiglass booth if needed. Faculty and staff who regularly interact with students are also tested weekly. At the end of each day, a courier takes the samples to the Broad in Cambridge, which generally returns results within 10 hours.

“The message we’re trying to reiterate is that you can’t just come and get tested once—it’s an ongoing program,” says Jennifer Schwartz, Wellesley’s medical director of Health Services. “Everyone for the most part has been really on board, and hopefully that is what will continue to make it a success.”

THE THREE WS

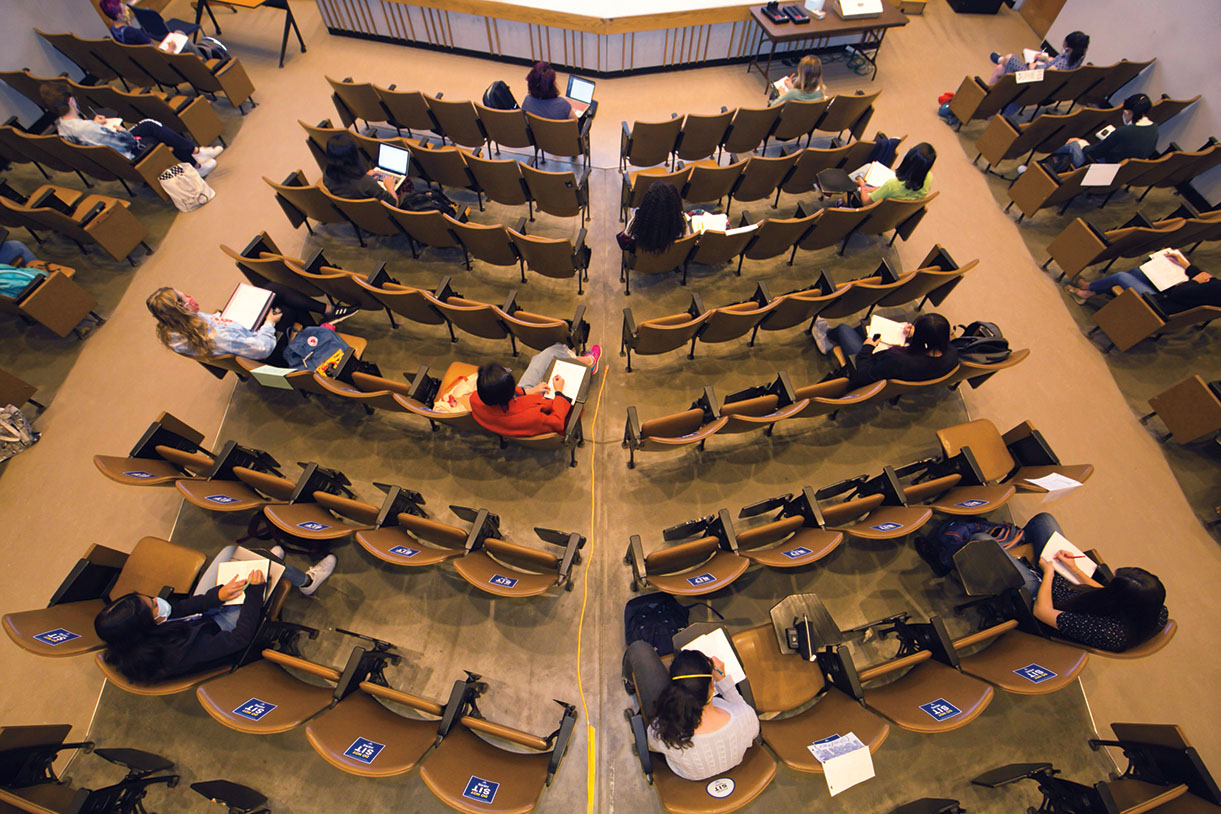

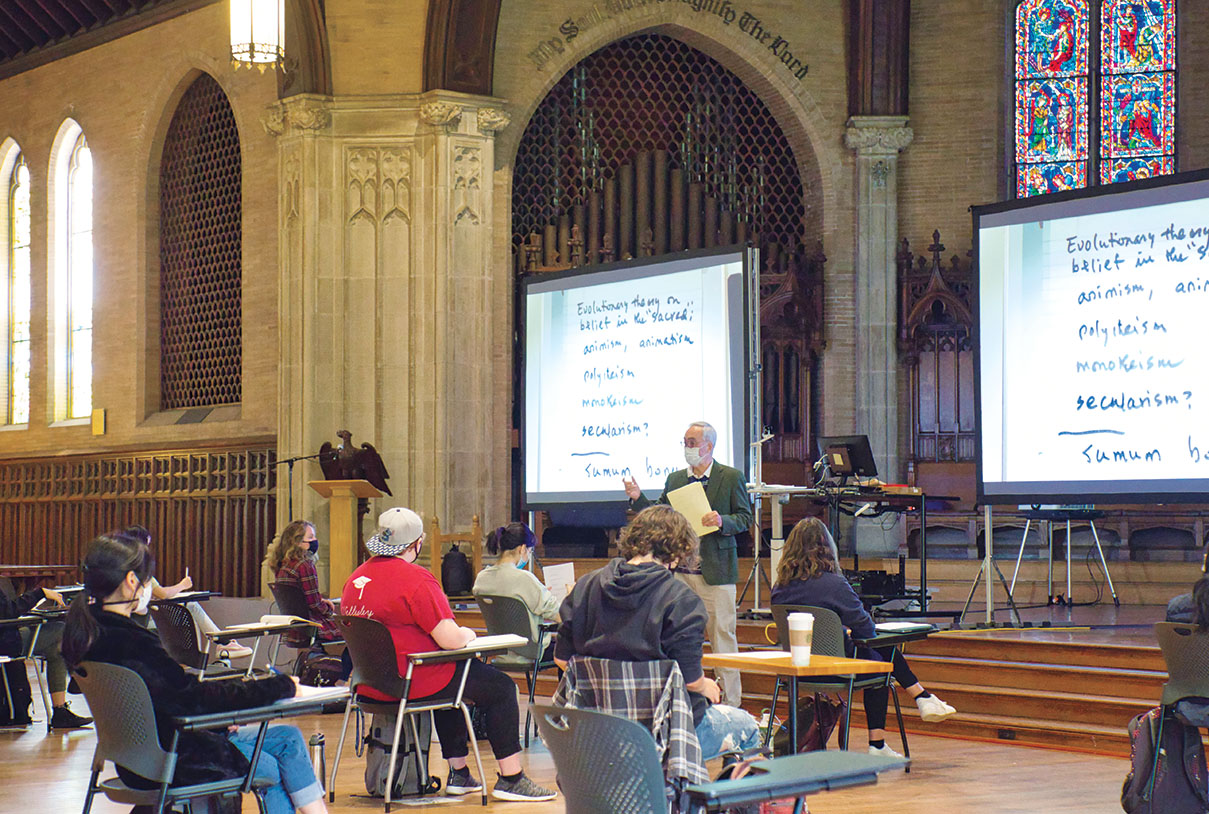

“At Wellesley, we’re all about earning the W,” said a community health video made this fall for students. In this case W means: “Wear your mask, wash your hands, watch your distance.” Masks and social distancing were stressed for the classroom, the lab, and even just hanging out outside. Large spaces like the chapel and Jewett Auditorium have been pressed into service for teaching. An active testing program was an important keystone for campus safety measures, as well.

Students schedule tests through the CampusKey app—which also reports negative results—and check in daily with a HealthCheck app that reviews a list of possible symptoms. Schwartz and her team follow up with students who report symptoms, assessing them virtually, and testing them at Health Services if necessary. If a student were to test positive, whether through routine or symptomatic testing, a provider from Health Services would immediately contact them to discuss the results. The student would quickly be moved to dedicated, isolated quarantine space on campus. Then contact tracers, on campus and through the town of Wellesley, would be mobilized, and additional students would be isolated if necessary. A student who tested positive would remain in isolation for 10 days, visiting virtually with a health-care provider daily. The overall cost of the testing program is estimated to be about $3.9 million.

The test itself uses a polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which amplifies and detects the virus’s genetic material. “The PCR test is the gold standard test right now. It’s the most sensitive and specific,” Schwartz says. The Broad’s version, which is FDA approved, costs $25 per test, a price that Lander says is possible due to the institute’s large testing volume.

Between mid-August and late October, when this issue went to press, over 26,000 routine tests plus a handful of symptomatic tests were done. Only three tests came back positive. (Visit Wellesley’s COVID-19 Dashboard to see current testing results.)

Schwartz and Petrulakis emphasize that frequent testing is only part of the picture. “The testing is not the prevention. The prevention is social distancing, not having big gatherings, wearing your masks, all of those things,” Schwartz says.

“There is not a magic solution to this. It really depends on everyone thinking of each other and complying with these pretty basic preventive measures,” Petrulakis adds. “But I believe in our students and our community, and I think we can do it.” On a sunny day in early September, Petrulakis returned to campus for the first time this fall, where she was greeted by a familiar yet novel sight: students, in masks, walking around campus, sitting on the grass, talking from a safe distance. Other than the masks, she says, “it felt like Wellesley College.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.