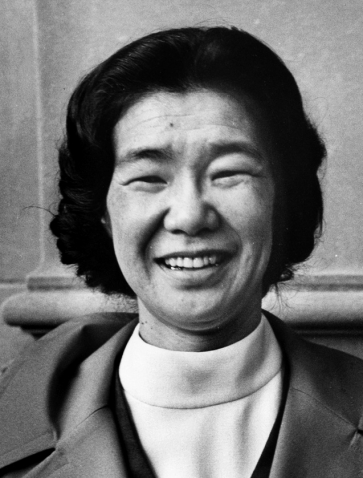

Emiko Ishiguro Nishino ’45—“Koko” to her classmates, colleagues, and friends—died on April 23.

A sui generis member of the Wellesley community for well over half a century, she first arrived at Wellesley from her home in central Pennsylvania in the fall of 1941, three months before Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Her older sister, Mariko, was already enrolled at the College. For fear that something terrible might happen to the Ishiguro sisters, Mildred McAfee Horton, then president of the College, invited them to stay on campus for Christmas. They did. Koko graduated from Wellesley just a few months before Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces in August 1945.

In those days, in the American mind, Japan was synonymous with “evil empire.” Executive Order 9066, signed in February 1942 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, ordered some 120,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans in California, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona to be removed from the “military exclusion zones” in those four states. American citizens of Japanese ancestry, despite having been born on US soil, were immediately reclassified as “enemy aliens.” They had 48 hours within which to report to public authorities. They were put on buses and trains, with shades pulled down, bound for destinations undisclosed to them, only to end up in remote desolate places from east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains to Arkansas. Along major highways, there were large signs, saying, “The only good Jap is a dead Jap.” The internees were told that the federal government was to protect them, but upon arrival, they saw the guns were pointed at them. They stayed in the camps until a year after Japan’s surrender.

Despite attitudes prevalent elsewhere in the country, Koko and her sister were sheltered at Wellesley. “There was no hostility,” she told a student publication in 1993. “I felt very much that I was a Japanese-American, and therefore I should do my part just like everybody else. The College felt that way. It was a wonderful response from the College.”

After Wellesley, Koko married Hiroshi “Herb” Nishino, who had been born in Japan but was brought to the United States as a small child. Because he had been living in California in 1942, Herb was interned for four years. Koko, being from Pennsylvania, was not affected by the Executive Order. Having been born in Japan, Herb was ineligible for naturalization as a US citizen under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which affected all East Asians. As soon as it was rescinded in 1952, he became eligible and became a naturalized US citizen. It was one of the most important days in the lives of Herb and Koko, until they were blessed with the birth of two boys, Vincent and Stephen, now of Holden and Waltham, Mass., respectively.

Koko’s long and varied involvement in, and indeed devotion to, Wellesley College began during that Christmas of 1941, when she and her sister stayed on campus. In 1976, she came back to work at Wellesley, serving over the years as an assistant to the president, as a development officer, as advisor to students of Asian descent, and as coordinator of services for students with disabilities. She advised Wellesley presidents from Barbara Newell to Diana Chapman Walsh ’66, advocated for members of the community with disabilities, and was always among the first to welcome students and faculty of Asian descent to the College. Koko was also president of the Wellesley Alumnae Club of Boston and treasurer of the Alumnae Association Board of Directors.

For many years after she retired from the College, Koko continued to volunteer for Wellesley. At many commencements, it was she who pushed the wheelchairs of students with physical disabilities as they received their diplomas. Somehow, she was able to find funds to promote on-campus events by and for Asian and Asian-American students. With a big smile on her face, when asked what and how she was doing, she often replied “various and sundry things.” In Koko’s case, that was literally true.

Off campus, Koko was a devoted communicant at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Weston, Mass. In this wealthy, nearly all white parish, Koko stood out. But, much more than physically, she stood out, because of “various and sundry” chores she performed for the church. In the 1980s, she was an active member of the development campaign for the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. She was one of the closest and most trusted friends of Bishop John Coburn, who made it possible for women to be ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church. Koko was also a friend and active supporter of the arts in Boston.

If I may be permitted to speak personally, Koko was one of the “character witnesses” when I sought naturalization as a US citizen as a conscientious objector in 1978. Again, in 1985, she was one of the presenters, when I became the first Asian-American ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Diocese since its inception in 1784.

With fond and grateful memories, I join so many of her former colleagues and friends in extending our gratitude and affection for Koko Nishino.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.