In the fall of 2016, the class of ’77 reunion planning committee held a conference call to discuss its upcoming 40th reunion. “Emotions were running really, really high,” remembers Michele Tinsley Leonard ’77. Leonard and others on the call had been very involved with the Black Lives Matter movement over the previous few years, and they saw Donald Trump’s recent election as part of a backlash. “Someone said, ‘We can’t go back to campus and do the same old same old,’” says Leonard.

Ultimately, Leonard, Sherry Zitter ’77, and Jessica Strauss ’77 planned a conversation about race during reunion, with classroom space provided by the WCAA. They expected one or two dozen alums—and were bowled over when some 75 people, representing every class at reunion, came.

That was the beginning of the Wellesley Racial Justice Initiative (WRJI), which in the fall of 2020 became an incorporated nonprofit organization, 501(c)(3) status pending, with Leonard hired as its first executive coordinator. Its mission is to actively promote racial justice in the U.S. and the wider world, advance inclusion, and eliminate both institutional and internalized racism.

A crucial moment in WRJI’s history was in September 2018, when the co-founders and several alums from other classes, including much younger alumnae, held their first group retreat on Cape Cod (with two alums attending remotely via video). “It was life changing, I think, because we all realized that we old activists … had something to teach the young ones, and they had a lot to teach us,” Strauss says.

WRJI is run by a leadership collective of alumnae of different races, ethnicities, and generations, and includes several alums who do diversity, equity, and inclusion work in their professional lives. Prior to last spring, WRJI’s offerings included sessions at reunions and at the WCAA’s annual BLUEprint volunteer training program, as well as program templates created for Wellesley clubs. But everything changed in 2020.

First, Leonard and Strauss point to the protests that swept the U.S. after the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others, and the incident in Central Park when Amy Cooper, a white woman, called the police on a Black man who was bird-watching. “No one can anymore say they don’t understand police brutality after 8 minutes and 46 seconds. No one can say they don’t understand how a white woman who voted for Barack Obama can just switch in a three-second phone call and endanger the life of a Black man for no reason,” says Leonard.

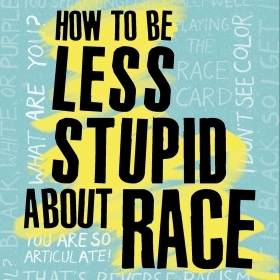

Also, because of the pandemic and the fact that “the whole world is on Zoom,” Strauss says, WRJI realized it could offer its programming directly, rather than going through alumnae clubs. In July, an opening conversation about race—which WRJI describes as a starting point for white alums and alums of color to “enter the dialogue, advance the learning process, and join the struggle for racial justice”—attracted 60 alumnae. Now, WRJI offers these conversations via Zoom each month. Every opening conversation is unique, but they are built on the foundational work WRJI has done at its retreats. “As we’ve developed the workshops that WRJI now offers, it comes from really intense work that we’ve done, and realized what works,” says Leonard. Strauss describes the opening conversations as “brave spaces” rather than “safe spaces.” The open conversations typically focus on the participants’ development of racial identity and how racism manifests in their lives. Some of the many other online events WRJI has held this year include a viewing of the film Dear White People followed by a discussion, and a book club that read How to Be Less Stupid About Race by Crystal Fleming ’04.

Leonard, who is an enrolled member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation and is also part Black, was one of the founders of Mezcla at Wellesley, which originally included Native American students. She is frustrated that more than 40 years after she was a student, the same conversations about race are necessary. “None of us want to have this conversation 40 years from now. … And it takes having to do the work, and acknowledging that there is work that needs to be done,” she says.

To learn more about WRJI, visit wrji.org.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.