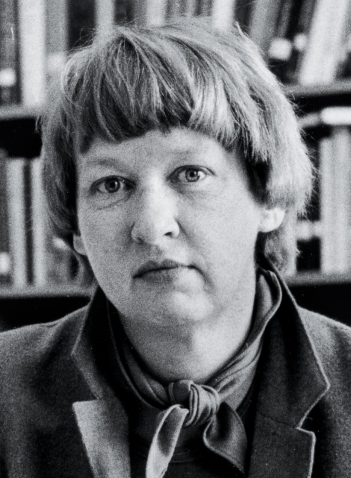

Blythe McVicker Clinchy, inaugural Class of 1949 Professor of Ethics and professor of psychology, died on April 23, 2014. She graduated from the Columbus School for Girls, received her B.A. from Smith College, M.A. from the New School for Social Research, and Ph.D. in human development from Harvard University. She began teaching psychology at Wellesley College in 1965 as an A.B.D. and mother of three young sons. Blythe taught at Wellesley until her retirement in 2000, and served as psychology department chair, psychological director of the Child Study Center, Faculty Fellow of the Pforzheimer Learning and Teaching Center, and research fellow at the Wellesley Centers for Women.

Blythe’s teaching and scholarship were synergistic: Her research focused on intellectual development and epistemology, and her teaching provided an arena in which to apply her research. Early in her career, Blythe collaborated with colleague Claire Zimmerman to test the applicability to college women of William Perry’s model of intellectual development. Perry’s model was based on college men, but as Blythe said, “In truth, we had no doubt that it was perfectly applicable, that Perry’s was a gender-neutral theory.” When giving talks, Blythe would mischievously shock her audience with the admission that she and Claire initially “threw away” interviews from those who didn’t fit Perry’s model, only gradually explaining how they revisited those interviews and learned from them.

That work formed the foundation for Blythe’s groundbreaking book: Women’s Ways of Knowing, co-authored with Mary Belenky, Goldberger, and Jill Tarule (1986/1997). Blythe and her collaborators vividly described the position of “received knowledge,” where students wait to be informed by authoritative experts, and “subjectivism,” where students accept their personal feelings and experiences as knowledge. They came to see the developmental value of these positions in the context of individuals’ lives. For example, subjectivism—deplored among academics—might be a significant achievement for a student who had previously felt silenced by “expert” interpretations. Similarly, being able to learn from others, a “passive” perspective belittled by advocates of critical thinking, could represent an important milestone for someone who had previously been unable to make sense of what they heard and read.

Most strikingly, Blythe and her colleagues contrasted that gold standard of academic and intellectual discourse, impersonal and dispassionate “separate” knowing, with the suspiciously mushy-sounding, emotion-accepting “connected” knowing. Blythe argued that using both positions flexibly was optimal. It was revolutionary to assert that much could be learned by “thinking with” rather than “thinking against” others’ arguments. Blythe anticipated, by decades, psychology’s current fascination with how emotion, rather than being the enemy of good decision-making and analysis, may facilitate and inform it.

Others often assume that Women’s Ways of Knowing describes a way of thinking unique to women, but Blythe was clear that various ways of thinking were found among women and men, albeit with culturally shaped differences in frequency. She identified herself, by inclination and initial training, as a “separate” thinker. Her appreciation of alternative perspectives, and ability to use connected knowing herself, were intellectual achievements, which she then helped make possible for others.

Blythe’s extensive service to the College reflected her intellectual dedication to understanding differences in how people develop beliefs about what knowledge is, how it is produced, and how they think about themselves as “knowers.” She led faculty seminars and new faculty orientations, and she co-founded the Wellesley Feminist Pedagogy Group. She spoke often of experiencing tension between the teaching goals of “relevance and rigor.” Though unfailingly modest about her success in integrating those goals, she inspired others by her ability to forge collaborative (connected) relationships with her students, which in turn allowed students (and colleagues) to learn from her incisive critiques.

Those of us who were fortunate enough to learn, work, think, converse, and laugh with Blythe will never forget her sharp, questioning intelligence, her playful sense of humor, the humility that made her receptive to new perspectives, and her gifts of collaboration.

—Ann Congleton, professor of philosophy, emerita; Annick Mansfield, institutional research director, Office of Institutional Planning and Assessment; Julie K. Norem, Hamm Professor of Psychology; and Claire Zimmerman, professor of psychology, emerita

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.