After constructing College Hall, the majestic building where 314 students lived and learned when Wellesley College opened its doors in 1875, Henry Fowle Durant bought three rowing vessels and docked them on Lake Waban. These high-railed boats—the Argo, Mayflower, and Evangeline—resembled whaling dories more than today’s sleek low-to-the-water crew shells, and they were propelled by the first collegiate oarswomen in the United States. These inaugural crews launched the College’s enduring rowing journey that by May 2016 found 16 rowers and two coxswains hoisting trophies as the NCAA Division III rowing champions. Blue Crew won the national championship again in 2022.

This year, as Wellesley’s crew races toward a spot in the 2023 championships, the College celebrates 50 years of intercollegiate rowing. How crews moved from unwieldy dories to untippable barges, from racing fours to top-ranked national powerhouse eights, is the story I’m here to tell.

Singing Songs to Sliding Seats

A fervent believer in the mind-body health benefits of vigorous exercise, Durant insisted on a daily hour of outdoor activity for students. But Wellesley’s first oarswomen were selected for their singing voices, as during the College’s first two decades, these rowers’ primary purpose was to entertain the College’s guests. Attired in elaborate boating costumes, the rowers sat primly side by side in pairs on immovable seats and pulled their oars with restrained, ladylike exertion.

Durant revered poetry as much as he took pride in his college’s rowers, and poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was the first Wellesley College guest to be rowed on Lake Waban. When Longfellow arrived on campus in fall 1875, he watched the christening of Evangeline, named in honor of his epic poem, before its rowers welcomed him aboard. After an unsettling row, the crew deposited its 68-year-old guest at the base of a craggy hill, which he climbed with difficulty under an archway of uplifted oars. Until his death in 1882, Longfellow visited College Hall often, but never again assented to be rowed to his readings.

By the early 1890s, rowers sat single file on movable seats in longer, lighter, narrower cedar boats that had replaced the bulkier originals. On special occasions such as Float Night, a tradition since the 1880s, class crews paraded in their boating finery through a crowd of spectators before inconspicuously removing their billowy skirts to row in bloomers. In 1893, many of Float Night’s 5,000 ticket holders came by train from Boston to watch the students row on a lantern-lit Lake Waban. Helen Shafer, Wellesley’s then president, assured anyone who might be concerned for the ladies’ well-being that they rowed “not for speed, but for skill and grace,” adding that “racing is not allowed, hence there is no temptation to overstrain.”

The class of 1887 crew poses on the steps of College Hall.

Courtesy of Wellesley College Archives

In 1897, Wellesley athletes competed against another college for the first time—losing to Radcliffe in tennis. It would take 73 more years for Wellesley rowers to leave Lake Waban to compete against another college’s crew. On a November afternoon in 1970, five members of the class of ’73—rowers Wendy Evrard Lane, Sally Brumley Keller, Liz Senear, and Gigi Coe, and cox Debbie Kaegebein—borrowed a racing four from MIT, then handily defeated two MIT women’s crews in a 500-meter race on the Charles River. They returned home with no medal, nor was their race included with the results of the men’s races. Senear ruefully remarked to The Wellesley News that the women’s race was planned “as the comedy event of the afternoon,” though neither she nor her fellow rowers had viewed it that way. Leading up to the race, they’d driven in the early morning to MIT to learn how to row a racing four, as Wellesley didn’t own one. The News sports columnist, Mary Young ’76, described the racing shell as a “long, skinny cardboard thin racer, tippy as a kayak,” much tougher to row than Wellesley’s wide “barges.” The 1973 rowers welcomed the challenge, savored their win, and pined for more intercollegiate competition.

Young had nailed the zeitgeist by seeing this MIT race as marking “the dichotomy … between the intercollegiate and recreational crews.” In fact, after it, MIT challenged Wellesley to a 1,000-meter race, and Radcliffe sent word that they wanted to race Wellesley in the spring. But without boats in which to practice or race, the answer from Wellesley’s water coach, Barbara Jordan, was succinct: “We cannot set up any races with anybody unless we have a [racing] shell.”

By the next fall, Wellesley had a racing shell—a wooden four residing on sawhorses in the boathouse. The day it arrived, Jordan asked me to row in it, which I did. Three of those who’d raced against MIT, me, and new cox Ridgely Ochs ’73 comprised Wellesley’s first intercollegiate team rowing a racing shell that the College owned. A dozen years later, Wellesley acquired a racing eight, the first step in transforming Wellesley rowers into national competitors.

From Festivities to Finish Lines

On Float Night in June 1905, 6,000 ticketed spectators squeezed onto the lawn sloping down to the lake. Henry Durant’s widow, Pauline, sat on the platform at Waban’s edge as the College’s fleet came into view. At dusk, large light machines cast colorful beams across the water as the coxswains brought their boats’ bows together and formed a star and then, for the first time, a “W.” Lifting their oars lengthwise into the sky, the oarswomen joined the glee and mandolin clubs in singing the crew and class songs, launching a decades-long tradition. That night’s event ended after the “varsity” eight, in which the College’s most skilled oarswomen sat, rowed “its lengthy shell back and forth with much skill,” according to the Boston Globe.

My grandmother Teresa Pastene, class of 1907, rowed in that boat.

In my grandmother’s senior year, Wellesley’s rowers were invited to race other women’s college teams on the Thames River in Connecticut when Harvard raced Yale in June. “We are not allowed to actually compete in races,” the president of the College rowing club reminded her fellow rowers. In March, the student body voted on the matter, and a Boston newspaper declared the decision: “Wellesley to Send No Crew.” The idea was said to be “entirely impractical” despite enthusiasm expressed by many of the rowers, including, I’d like to think, Teresa Pastene. In her final class crew competition, she stroked the senior crew to victory “by unanimous vote of the judges,” according to the College News. When the boats were put away in June 1907, “the large Hunnewell Rowing Cup [was presented] to Miss Pastene.”

Wellesley’s crew team celebrates after winning the 2022 NCAA Division III National Championship in Sarasota, Fla.

Photo by Mike Janes

Miss Pastene graduated, married, raised four children as Mrs. Edwards, and never rowed again.

In fall 1971, her youngest daughter, Jean Edwards Ludtke ’45, stood on a dock at Onota Lake in Pittsfield, Mass., to see her own daughter cross the finish line ahead of the Williams College crew. In spring 1972, the five of us launched our four into the swollen, swirling Connecticut River. That rainy afternoon, we defined victory as just finishing the race without having our wooden boat punctured by one of the many free-floating logs loosed by the storm. If one of us wore Wellesley blue, it was by chance. No one’s T-shirt and shorts matched anyone else’s. Crew outfits, like racing eights and coaches who understood rowing, remained a distant dream as 1973’s pioneering intercollegiate rowers raced on.

At Home on the Charles

Women were allowed to compete in eights in the prestigious Head of the Charles Regatta for the first time in fall 1972. Wellesley seniors borrowed an eight to race three miles against 12 other boats, finishing seventh. The next fall, Wellesley raced its first eight in the Eastern Sprints, earning a spot in the finals on the Charles River. Congratulating the rowers, the Wellesley News observed: “Crew has come a long way in the last three years at Wellesley, largely due to the enthusiasm of those (now notorious) ‘crew jocks.’ This kind of dedication to team sport is a welcome breath of fresh air at a school with such an incredibly stagnant intercollegiate sports program.”

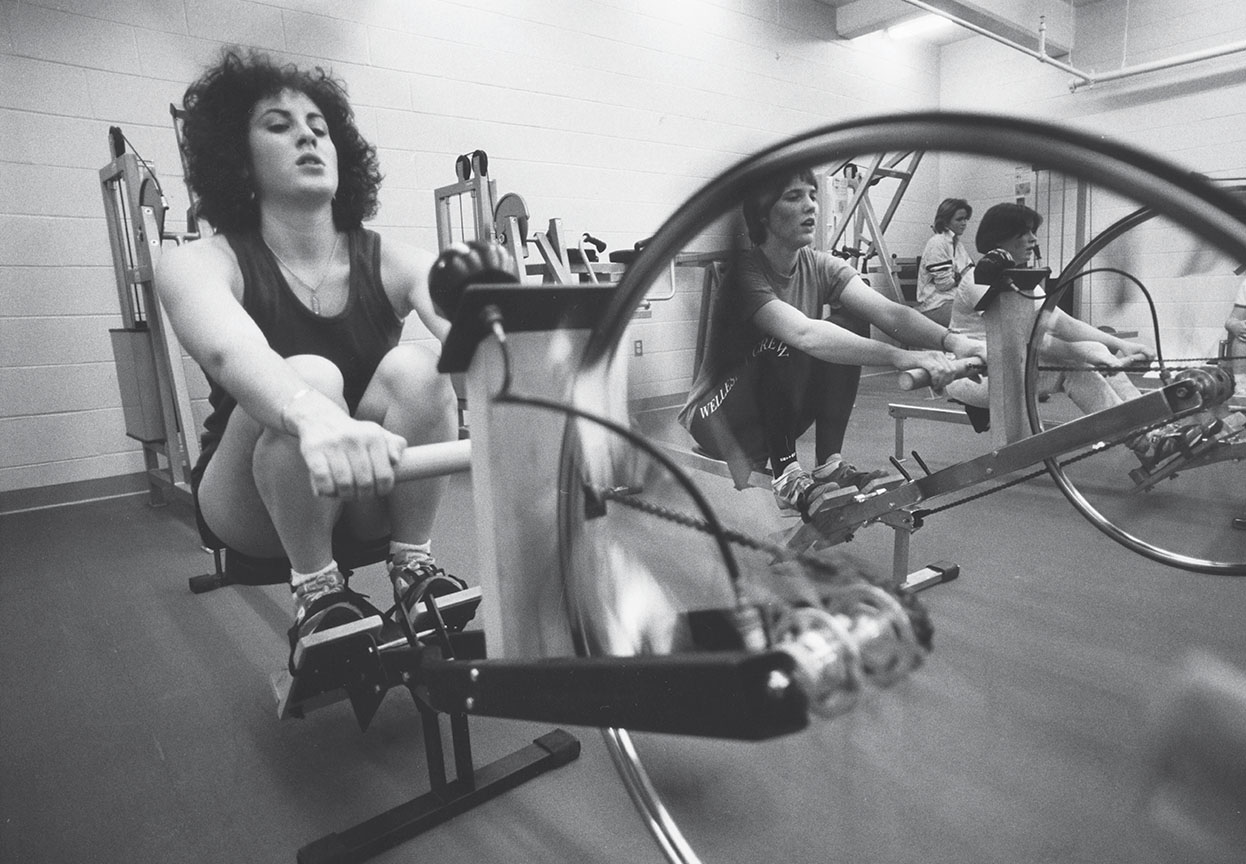

It wouldn’t be until 1998 that Wellesley’s competitive rowing team moved its eights into its permanent boathouse on the Charles River. Before then, the College rented space at Boston University’s boathouse, and the rowers met at 5 a.m. at Wellesley’s gym to drive to the Charles River so they could train at distances that would prepare them to compete in 2,000-meter races. Lake Waban offers crews only 700 meters to row at their hardest.

This shortcoming likely played a surprising role in the unexpected inclusion of Wellesley’s lightweight four in the 1977 National Rowing finals. Three years earlier, Wellesley had hired 21-year-old Mayrene Earle to teach physical education, her major at Northeastern. She also coached crew—recreational and intercollegiate—though she knew nothing about the sport. “I felt like a babysitter,” Earle told me, so she found rowers who taught her to coach. Joel Ristuccia, a former Yale rower, was one of them. In exchange for storing his single at Wellesley’s Lake Waban boathouse, he joined Earle in the launch and coached her rowers. “I’d ask him questions,” Earle says. “I needed to learn everything.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.