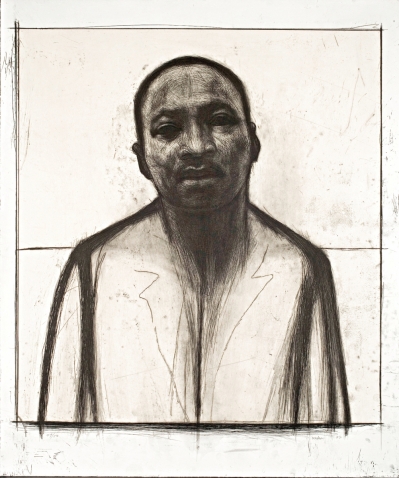

We think we know Martin Luther King, Jr.; his image has long been appropriated by American popular culture. But this etching and aquatint by John Wilson—owned by the Davis Museum—compels us to look again. We are drawn to the attitude of the head, with its slight tilt that allows for our interpretation of Dr. King’s expression. We see sadness, resignation, patience, reflection, exhaustion—relatable human emotions that we don’t always associate with this iconic figure.

Wilson, who was African-American, portrayed the Civil Rights leader repeatedly during his career. This work is based on studies for a memorial that was commissioned by Congress for the U.S. Capitol building in 1985. The bronze bust that Wilson sculpted of King, now sited in the Capitol rotunda, is heroic and dignified, as befits its location. The etching, by contrast, is shaded and nuanced; King’s familiar features are less delineated, the mood is heavier. By keeping the details minimal, Wilson paid homage not only to King’s public legacy but also to his private humanity.

The artist—who was born in Roxbury, Mass., in 1922 and died last month—was long concerned with issues of racial equality and social justice. “His entire body of work reflects an interest in not only recording the experience of black people in the United States, but also in setting forth a dignified symbol to represent African-Americans in a way that is both timely and eternal,” says Katherine French, director of the Danforth Museum in Framingham, Mass., who curated a survey of Wilson’s work in 2012.

Wilson’s talents were recognized early, when he was a teenager. His art teachers at the Boys Club were students at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and they helped him obtain a scholarship to study there. He received two fellowships to go abroad: to Europe to work in the Paris studio of Fernand Léger in 1948, and to Mexico City, where he was influenced by the Mexican muralists working in the style of José Clemente Orozco.

Wilson’s experiences in Europe and Mexico reinforced his desire to use his art to advance social goals. Over his extensive career, he challenged racism not through didactic means but by creating works that have the potential to transform us. By asking us to look more deeply at the Civil Rights leader, Wilson urged us to see the man behind the icon.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.