If my life could be summarized by a bumper sticker, it would be something like: “I’d rather be procrastinating.” If I had a motto, it would be: “Why do something today that could easily be put off until tomorrow?”

I am a procrastinator. I have been for as long as I can remember. At Wellesley, some friends used to refer to me as “The Vortex” because of my ability to suck people into doing things, typically when studying would have been the more prudent option than, say, watching The Thorn Birds mini-series (roughly eight hours of glorious melodrama).

When this magazine’s illustrious editor first suggested I write a piece on procrastination, I thought she was joking. Or perhaps taunting me in some cruel way. She knows I’m a procrastinator (I used to work in the magazine office); everyone knows I’m a procrastinator. But she was serious, and I was intrigued, so I accepted. [Editor’s note: The first thing she did after accepting the piece was ask for an extension.]

Perhaps this article would allow me to get at the heart of my procrastinating tendencies. I could blame them on my early fascination with Scarlett O’Hara and Gone With the Wind. Or my writer’s need to work under the pressure of a deadline. Or perhaps I would finally turn the proverbial procrastination corner, and finish this assignment early! [Editor’s note: She turned this piece in at midnight on the day it was due.] If nothing else, perhaps I could determine why, although lots of people procrastinate, not all of them are, in fact, procrastinators.

Procrastinators of the World, Unite!

Putting off doing something unpleasant is a fairly typical human response. There are very few people in the world who relish diving into a sink full of dirty dishes or writing a detailed work report. Studies indicate that anywhere from 90 to 95 percent of people report procrastinating occasionally. However, 26 percent of Americans consider themselves chronic procrastinators, according a 2007 study published in Psychological Bulletin, a journal of the American Psychological Association. [Author’s note: I like to consider myself a functioning procrastinator.]

Of course, not everyone realizes that they are procrastinators. Michelle Tullier ’84, author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Overcoming Procrastination, had her epiphany at a rather interesting time. Although she had done workshops on time management and procrastination for years, she says, “Until I sat down to write the book, I think I was in denial. I was unwilling to admit to myself and others that I was a major procrastinator myself.” Now Tullier sees the patterns in her behavior more clearly. “To finish my doctoral dissertation, I stayed up for three days and three nights straight,” she says. “I don’t recommend trying that at home.” She continues to work with issues of time management, specifically in career development, in her current role as the executive director of the Center for Career Discovery and Development at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “Once I realized it was OK to acknowledge that [I am a procrastinator], it really made me even more qualified to help other people with it.”

But what, at its heart, is procrastination? One of the earliest English dictionaries defined the word as just “delay,” but this certainly isn’t the full sense of the word as it’s used today. “Procrastination is avoidance,” says Robin Cook-Nobles, director of Wellesley’s Counseling Service and dean of the Office of Intercultural Education at Wellesley. “When we’re threatened in life, we’re wired to respond in certain ways, and avoidance is one of them.”

Cook-Nobles runs a workshop on procrastination every semester to help students with procrastination issues. “I try to empower them to be proactive and take charge,” she says. “When they leave [the workshop], they have a framework and different techniques, but they also have a different way of looking at what procrastination is that’s more empowering.”

In the workshop, they look at what is and isn’t procrastination. For instance, students fill out schedules with everything they have to do, from classes to homework and long-term assignments to extracurricular commitments. “They beat themselves up all the time, but I tell them, sometimes you’re not procrastinating. Just realistically, your schedule is too full,” Cook-Nobles says. “We talk about what to give up, and the students often feel like they cannot give up anything and that they have to do everything.”

But doing everything can be daunting. Which is why it’s probably better to … knit? Lucy Archer ’12 is a firm believer in what she’s deemed “procrastiknitting,” and she finished an entire sweater (complete with thumbholes) in a week and a half. Of course, it was the week and half she was supposed to be studying for exams. “I ended up giving it, and all my other yarn, to my roommate to hide until that set of exams was done,” Archer says. “For women who will, we’re very good at being women who almost won’t.”

Why We Don’t Do What We Don’t Do

If you ask procrastinators why they’re putting something off, you’re sure to get a variety of responses, often starting with a laugh, some mention of “needing to feel the pressure,” and ending with a shrug. Most of the time, procrastinators don’t actually know why they’re procrastinating. [Author’s note: I like to think I procrastinate because it’s the one thing at which I’m sure I truly excel.]

While researching her book, Tullier found that household chores consistently came up as one of the top things people put off doing, along with other simple tasks like scheduling appointments. “This is how procrastination happens,” she says. “We think it through too much, we often dwell on the negative, or we overcomplicate things.”

Cook-Nobles agrees. “Procrastinators throw time away,” she says. “They’ll say, ‘I need an hour,’ but it has to be right on the hour or the half-hour. They have these rules in their head.” And if those rules aren’t met, the work doesn’t get done. The size or importance of the work often doesn’t seem to matter, either. “It could be anything. It could be a two-page paper,” Cook-Nobles says. “It has nothing to do with their ability to do the task.”

And while some turn to craftwork to procrastinate, others procrastinate over the crafts themselves. “When my sister-in-law was pregnant with her first child, I started crocheting a baby blanket,” says Beth Iandoli ’85. “I finally finished it a year ago. For that child’s baby shower. As in, that child was having a baby.” And although she had 27 years to complete the project, Iandoli still had to stay up until 2 a.m. on the day of the shower to finish it. [Author’s note: Procrastinators apparently like to coin new terms for their procrastination, perhaps as yet another form of procrastination. Iandoli’s term? “Procraftination.”]

So why can’t we finish the paper or the baby blanket or the report in time? “It’s often a combination of inner and outer factors,” Tullier says. “So often the advice given out there about overcoming procrastination either focuses on the psychological aspects or the more environmental factors. The reality is, it’s often a combination of both.”

External or environmental factors often relate to the need to be more organized or not having the information necessary. “Some people put off doing something simply because their desk … or their computer desktop is messy,” Tullier says. “So much of the time, it’s about not putting roadblocks in your way, and we create those by having messy surroundings or not reaching out to other people as resources.”

Internal factors include things like perfectionism, fear of failure, and even the fear of success. “The fear of success, especially for Wellesley women, seems like such a ridiculous concept,” Tullier says. “Wellesley women aren’t afraid to be successful. But what that often means … is that if you do something on time and you do it well, you’re going to be expected to do it again, and probably expected to do it even better and faster.”

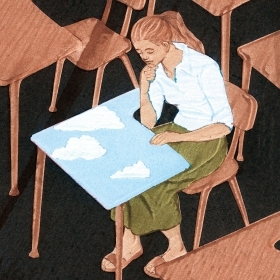

Cook-Nobles points out that procrastination can also be a response to external pressures. “Sometimes, procrastination is a passive-aggressive expression of resentment or anger,” she says. “Say someone is feeling pressure to be a doctor or a lawyer, but they really don’t want to do it. So they don’t have the motivation, and then unconsciously, they get out of it by not doing so well.”

Some people may think they are procrastinators, but there might be deeper issues at play. There could be undiagnosed learning disabilities, and that, of course, is not actually procrastination. At Wellesley, students can be assessed at the Pforzheimer Learning and Teaching Center for additional support. Cook-Nobles also notes that sometimes mental-health issues can be at the root of what some consider procrastination: “If you’re depressed, you might lack motivation, which could result in getting behind academically.” Students can seek support at the Stone Center, and class deans are often helpful here, as well.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.