The crowd was crushing. I could hardly breathe. If I didn’t allow my bones to soften, let my right shoulder fold over my collarbone, suck in my ribs like an accordion, I feared I would crack.

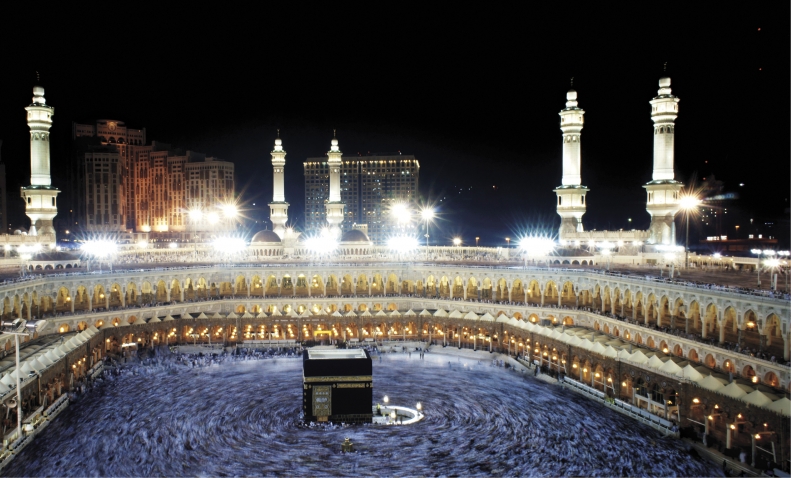

In a place as monumentally alive as the Ka’aba at the center of Mecca’s Great Mosque during Hajj season, no one wants to get hurt. With more than 22,000 medical professionals at the ready, EMS squads standing by, emergency clinics tucked into tiny openings under the Great Mosque, and an ultra-modern control room staffed with people watching the pilgrims’ progress via myriad mounted cameras, it would still take a proverbial lifetime to get from the midst of this spiritual maelstrom to a stretcher.

I didn’t want to miss a nanosecond of the tumultuous, transcendental, unifying experience of circling this ancient shrine with several hundred thousand other human beings, because I was there as a reporter, not a participant. I didn’t know when I’d get a chance to experience it again. So I let my bones liquefy.

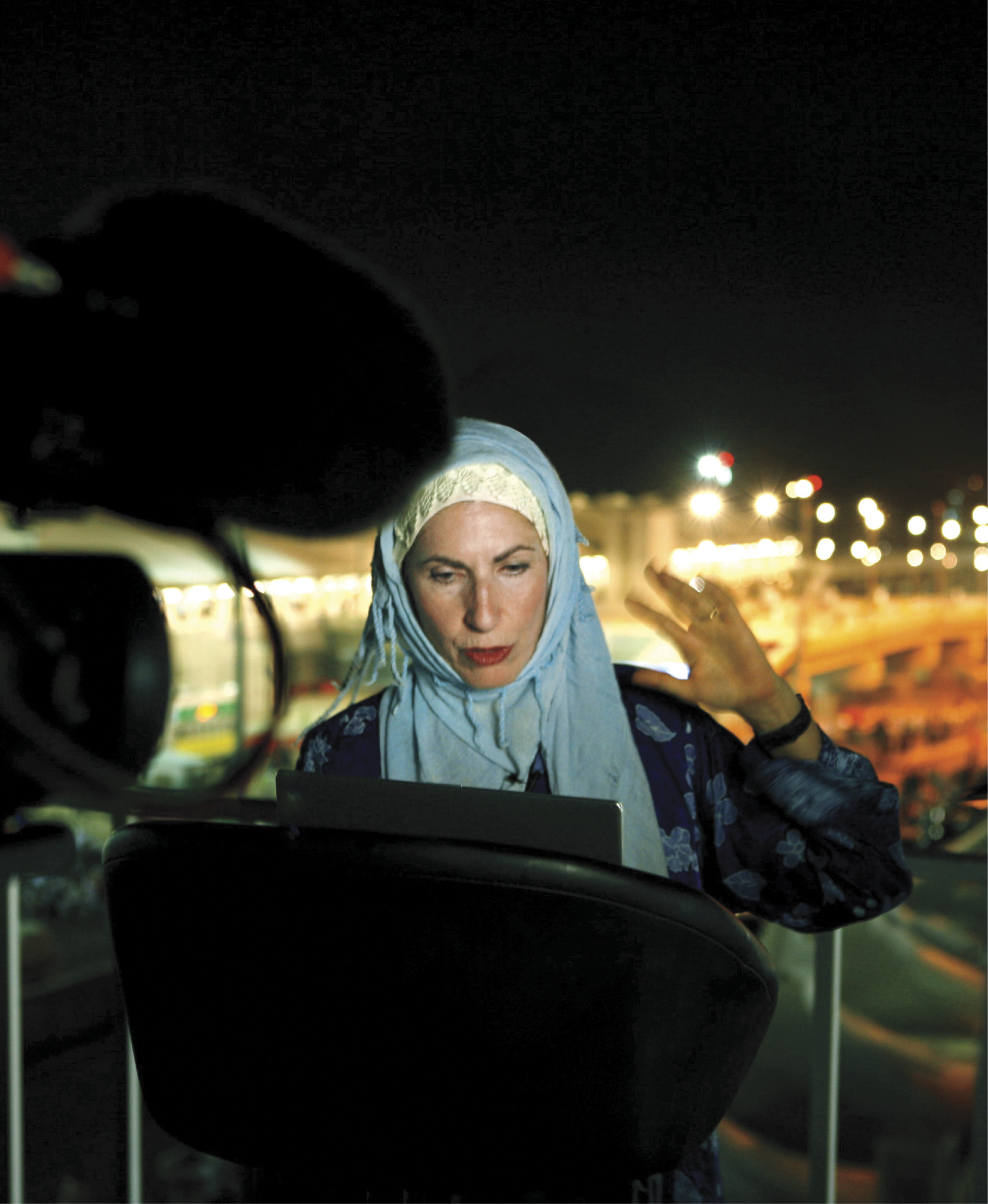

I’m no newcomer to covering the iconic pilgrimage that every able-bodied Muslim is encouraged to make once in a lifetime. This past October, I was in Mecca and Medina in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and filmed the great pilgrimage for national broadcast on PBS for the third time.

So I thought I knew what to expect: long hours, exhaustion, getting lost from time to time, camera batteries dying at just the wrong time, and random people objecting to my work. I also expected spiritual insights, connections, and miracles. But this journey hurled more at me. It was a graduate-level course in maintaining sanity and humanity in the face of incompetence and arrogance. It was a how-to on battling my own feelings of impotence and fury. Only swimming in the whirlpool of the tawaf —the circling of the shrine called the Ka’aba, a black box-like structure—did I find some peace and absolution, the promised rewards for people practicing pilgrimage. But I wasn’t practicing. I was working. At the time, I thought the two were different.

We were filming a group of Americans making the Hajj with the Islamic Society of Boston. One advantage of working as a documentary filmmaker is you may grow close to some remarkable people over a compressed period of time. Call it luck, fortune, coincidence, or karma, but among the remarkable people on this adventure was Amira Quraishi, Wellesley’s Muslim chaplain.

A native of Palo Alto, Calif., Quraishi and her husband Husam Ansari, an ophthalmologist, moved to the Boston area recently, both taking new jobs. Quraishi faced her unexpected trials on the pilgrimage as I faced mine. And we both took courage from a foundational story of the Hajj, the story of Hagar.

Hagar’s Quest

As second wife of Abraham, the patriarch of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Hagar didn’t have it easy. She joined the family as a slave to Sarah, wife No. 1, who could not conceive. Sarah presented Hagar to Abraham, hoping they’d all enjoy an heir. When Hagar got pregnant, Sarah was not kind to her. After Hagar’s son, Ishmael, was born and Sarah later had her own baby, Isaac, Sarah deemed there was not enough room in Abraham’s tent for both wives and both sons. Wife No. 1 wanted wife No. 2 and her boy banished.

Hagar ended up in the desert, and Muslims believe that desert is the one where Mecca is today. There, she faced a great trial: She had to find water to survive. “As a mother, all you really care about is your child and getting your child what he needs or what she needs,” said Quraishi admiringly, early in our trip. She would remember Hagar’s strength and unrelenting quest to thrive in the days to come.

In the Bible, God tells Abraham and Hagar that He would make a great nation from their progeny. So when Abraham left Hagar and Ishmael in the desert with some provisions, he left her with a lot of hope. She believed to the point of knowing that God meant for them to survive. But she did not sit back and wait. She searched until she found water, a well that has since been called Zam Zam. Whether you believe these stories from Genesis and the Islamic narratives or not, they—like the myths of many cultures—resound with power for humankind and for women in particular.

In 632 C.E., Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, turned Hagar’s heroic and ultimately successful search for water into a ritual in which every pilgrim participates as part of the Hajj. The multitude hurry back and forth seven times from end to end of a huge air-conditioned corridor that’s over a quarter of a mile long. It is said that the two hills Hagar used as lookout posts are encased within its sloping marble floors.

“This is my favorite part,” Quraishi told me in a sweet shop at the Hilton Mecca, just across the plaza from the Great Mosque. “And as a woman and as a mother, it’s so gratifying and exciting that one of the main pillars of Islam is literally following in the footsteps of a woman.”

Ancient and Modern Mecca

The Hajj begins in Mecca—the mother of all meccas. Hagar’s city is ages old. I call Mecca “Hagar’s city” because the spring she found meant she controlled a most valuable currency: water. She and Ishmael became important in a small but growing community. Scattered tribes that had settled there recognized her as the owner of the well. The city is nestled into the rugged mountains of the western Arabian Peninsula. It was an important stop along the ancient spice route from Yemen to Damascus. It is also, of course, home to the Ka’aba.

Worship at the Ka’aba works this way: People walk around it counterclockwise. Scholars imagine that not a day has passed in thousands of years without humans circling the Ka’aba. Imagine being part of a ritual so constant. That’s where I was, being crushed last October, while watching out for the safety of one of the pilgrims I was filming. As I looked around I saw that lots of us were watching for others’ safety. We had to. If one of us fell, we could all go down.

“The Ka’aba has been destroyed by floods and rebuilt over and over again,” explains Imam Johari Abdul-Malik, director of outreach at the Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center in Falls Church, Va., who appears as a scholar-expert in the PBS film I am making. “Now it’s a cuboid type structure made from stone blocks. There are people who desire to touch it as if they are touching the original stones. This is not the intent. It is a house for Allah, but the building itself should not become an object of worship.”

Muslims believe the first call to pilgrimage came from Abraham. He was born millennia ago in what is now Iraq, or Turkey, or Iran. They say he walked with his family and flocks throughout a region that today we view as hostile and dangerous. Through great Aleppo he came, the Syrian city now a ruin of its former self, milking his goats. Citizens of Aleppo used to tell tourists that Abraham shared the milk with everyone nearby, turning strangers into friends. The name “Aleppo” comes from halab, which is Aramaic, Hebrew, and Arabic for “milked.” The man was legendary for his open-tented hospitality, which included Hagar and Ishmael until Sarah got jealous.

Nowadays Mecca boasts much more than Hagar’s well, which still flows to refresh daily visitors. It’s got one of the tallest buildings in the world and a year-round population of 2 million. Those numbers double and triple during Islam’s sacred seasons: the Hajj and Ramadan, the month of fasting. There’s an Islamic museum with artifacts dating back 1,400 years, and a high-tech, virtual museum about the life, times, and teachings of the prophet. Lots of hotels; no bars. March through September can be very hot.

Capturing the Hajj on Film

The first time I covered the Hajj was in March of 1998, when I made a three-part series for public television’s Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly. Privileged to be the first American woman to report the Hajj for US broadcast, I found myself having to choose between 105+ F in the sun or 105+ F in the shade of buses that were idling everywhere. In every way, it was a trial by fire: I arrived with no permission, no crew, and no idea where to find the main character I’d seen off at JFK in New York just a week before.

On that journey, this skeptic experienced the power of prayer in real time. After ping-ponging from one government office to another across the congested city, pleading for a press pass, I returned to my hotel room on the verge of defeat. “Wellesley women would rather die than fail,” I remembered my colleague Judy Towers Reemtsma ’58 telling me when we were at CBS News together in the 1980s. So I prayed very hard, with my head to the floor; Muslim ritual prayer literally brings you to your knees. The instant I said, “Amen,” the phone in my room rang. “Your prayers have been answered.” It was a man’s voice. Suddenly I was credentialed and began paving a path toward success.

In 2003, I directed an hour-long documentary called Inside Mecca for National Geographic Specials. By now, I was a believer in miracles. So when one of my three main subjects, an Irish-American woman, was nowhere to be found among tens of thousands of tents and 2 to 3 million people on the vast Plain of Arafat on the most important day of the pilgrimage, I didn’t panic. For three hours, my Saudi government associate and I wandered among the tents and lightly leafed neem trees, looking for the campsite where she was supposed to be. Walking through that February afternoon, we saw people weeping with sorrow for mistakes made in the past. We heard cries of joy. People gave out water. On we trekked, our search bearing no fruit. Until I surrendered. I utterly gave up, as in throwing my troubles aloft for a greater power to resolve, rather than casting hope downward, resigned. “Muslim,” after all, means someone who submits to the will of God. “God is most Merciful and Compassionate,” I said to my Saudi companion Khaled, quoting the Qur’anic verse Muslims use in every daily prayer. “So we will find her.” Within minutes, we were inside her tent.

Gender Disrespect

The current film that I’m working on is for the PBS flagship station WGBH, the one that brings you Downton Abbey and Sherlock. It premieres nationwide in December. We’re producing a six-hour series on pilgrimage in diverse faith traditions: Buddhism, Hinduism, the Yorùbá religion, and the Abrahamic triad. Teams went to Lourdes with wounded American veterans, to Jerusalem, and I took on Mecca and the Hajj once again.

I got slammed from the get-go. In 2003, I was assigned a competent and effective government official who accompanied me on my National Geographic project. This time, I was assigned just the opposite: a 20-something, let’s call him “Ahmad,” who knew nothing about journalism, filmmaking, hard work, or manners. This young man’s tasks were simple: make sure the car and driver were ready and waiting to take us from place to place, walk with us where cars could not go, and show our papers to officials who inquired about our legitimacy. Instead, neither he nor the car showed up on time; when we were stopped, he did not show our permissions. Rather, he went for tea with whoever had halted our work. I’d never seen anything quite like Ahmad’s insolence and antagonism before.

Meanwhile, we carried on as best we could, keeping up with our pilgrims, who were at prayer before dawn every day and bedded down well past midnight. Sometimes, it seemed we were functioning on coffee and intention alone. I’d negotiated permission to conduct interviews with Wellesley’s Muslim chaplain, Quraishi, and her husband inside a major hotel one day, and Ahmad showed up ostensibly to vouch that we were in fact journalists sponsored by the government (he had been hiding our press passes for days). Instead, he argued with the hotel’s general manager against letting us proceed. To his credit, the manager pulled himself up to full height and said, “Young man, I will decide what happens and what does not happen within the walls of my hotel.” He turned to me and nodded, “We’ll set up a space for you.” Ahmad consistently treated me with such disdain that I finally asked my male crew to speak with him on my behalf. In more than 30 years of reporting from Arabic-speaking and Muslim-majority countries, there was only one other time that I experienced any gender-based disrespect. In that instance, the perpetrator was immediately scolded by his superior, an Iranian ayatollah.

Inspiration From Hagar

Quraishi got slammed halfway through her pilgrimage trip. One night in the enormous tent city of Mina, snuggled in a valley between the metropolis of Mecca and the neem tree-lined encampment of Arafat, she rolled over on her mattress, was startled awake, stood up suddenly, and twisted her knee on the wobbly mattress. Badly. She was in a wheelchair for the rest of the journey, struggling with anger and disappointment, boarding buses and negotiating crowded hills and valleys. A mother and a professional accustomed to handling everything for everyone, Quraishi found it hard to let others help her.

“I don’t think I’ve really ever been in this position before,” she confided. “If I try to walk, it will slow everybody down and I’ll be in a lot of pain. One of the hardest things is really to let people help you.” She had to let go, submit to an unwelcome reality and a new and perhaps welcome reality: that others wanted to help her and that it was OK to let them.

“Everyone’s behind you,” her husband, Husam, reassured her, while friends and strangers surrounded them, offering to carry her things, push the wheelchair, and bring her hot tea and ibuprofen.

I am also accustomed to handling everything that comes my way. But my efforts seemed thwarted at every turn. As a journalist covering a religious pilgrimage, I let myself tiptoe across the line separating work from involvement—as I did when I slipped into the crushing swirl of humanity around the Ka’aba. I coped with my unwelcome reality by allowing sacred metaphors of the Hajj to buoy my spirit. The story of Hagar’s unflagging efforts and the tale of Abraham’s other great test kept me afloat.

The Islamic story goes that when Abraham was confronted with the awful task of sacrificing his son at what he believed was God’s command, the devil showed up to convince him to stop. It took all of Abraham’s inner strength to resist that temptation. He was determined to do God’s will and threw stones at Satan to shoo him away. Per instructions from Muhammad the prophet, a symbolic stoning of the devil is one of the final rites of the Hajj. Pilgrims throw stones at enormous pillars representing Satan, showing that they, too, will resist temptation in the world to which they’ll return once the pilgrimage is complete.

Quraishi performed this rite in her wheelchair. “I found myself feeling so alive, so happy, seeing that God is stronger than any of those stupid things that we give in to,” she said. “So it was really enlivening for me.”

As I directed my crew through filming this rite—called the jamarat—I mused that perhaps God had sent a personal Satan to test me. I reminded myself of what we read in the Qu’ran, “God does not burden anyone with more than she can bear.” So I determined I’d trust, surrender, and throw symbolic stones. I had to believe something good would come from my experience with this obstructive associate.

I saw that I needed to be more like Hagar. She did not throw up her hands in resignation or defeat. She asked God, “Where is the water?” persistently until she found it. She was the B.C.E. version of a Wellesley woman. It dawned on me that Hagar had been my role model since the first time I’d come to cover this event.

So where was my water?

Since then, my water has come in seeing what we actually captured on film and not staying stuck in the muddied memories of that difficult passage. Throughout the deliberate process of filming in the field and filmmaking in the edit room, I revel in the depth of character of all those we interviewed. My editors delight to work with their thoughtful comments, the uncommon landscapes, and rarely seen rituals that we reveal in this film. Yet still it demands effort. Each talented editor and writer has a point of view, an artist’s eye, and concerns for content. I am substituting effort for the struggle I felt on location in Saudi Arabia, sure that we will work our way to something wonderful.

Because the challenges continue even after each pinnacle is reached. The “Satans” that bedevil our daily lives allow us to test our dignity and integrity in dealing with challenge. Will we simply suffer? Or will we surmount?

My water is an understanding that pilgrimage is a state of being, whether you’ve set out to cover it or to participate. That ultimately the professional and the personal are reduced to one single element: the self on the road of life.

Anisa Mehdi ’78 is an Emmy award-winning journalist and filmmaker based in New Jersey. She specializes in religion and the arts.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.