A circus atmosphere surrounds College Road as cars drive slowly past the nearly naked figure of a man, his eyes closed in sleep, his arms outstretched. At the side of the road, people mill around him, posing for the camera. They reach out hesitantly to touch his skin, laughing uneasily.

The “man” is actually a sculpture titled Sleepwalker and its outdoor installation as part of the Davis exhibition, Tony Matelli: New Gravity, has generated intense controversy on campus. While many people see the hyperrealistic sculpted figure as representing little more than a paunchy, middle-aged guy in white briefs, others find the figure deeply disturbing. They argue that Sleepwalker undermines community members’ sense of safety by triggering unwelcome associations with sexual assault. Some students circulated a petition to move the sculpture inside the museum.

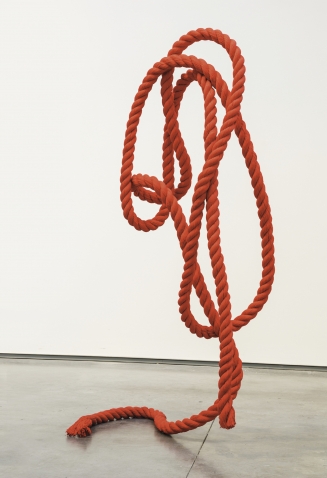

The controversy has become a sideshow to the rest of the exhibition, which includes imagery of a variety and depth that Sleepwalker only hints at. Inside the Davis, there’s a second figure of a sleeping man; this time he’s young, fully clothed, and levitating eerily above the gallery floor. Other sculptures involve similar feats of weightlessness, including coils of thick rope that twist toward the ceiling like cobras dancing to a snake charmer’s tune, and a vase of stargazer lilies in which the branch of flowers is turned upside down, poised gracefully on the lip of the container.

Matelli’s work emphasizes the transitional space that exists between opposites: heavy and light, awake and asleep, interior and exterior. In the Davis’s lower gallery, he’s created large, opaque “windows,” which have been suspended from the ceiling. The “glass” in the darkened windows is broken; its neglect suggests a larger malaise in the life of the building and its occupants. Matelli’s sculpted windows also include details such as a pair of wet socks, a cactus plant, and a dead bird that invite viewers to invent their own stories.

Interpretations of Sleepwalker run the gamut from creepy stalker to lost soul to sad sack. Seen from the window of the Davis’s upper gallery, the man on the lawn below looks vulnerable, exposed to the elements, cut down, alone. The distance lends perspective on the sleepwalker’s existential plight, which is why Matelli and Lisa Fischman, the Davis’s director, sited the figure there.

Up close, however, the figure arouses curiosity, aversion, pity, and humor. People marvel at the uncanny resemblance to a living, breathing human being. They circle the figure warily, as they would a visitor from another planet, even though they know it’s art. They wonder, “Is it supposed to be funny or serious?” and “Can I touch it?”

Matelli says he’s fascinated by the moment when someone first encounters one of his sculptures. In the first instant they think it’s real, and in the next they realize it’s a work of art. This, too, is a marginal state, transitioning from belief to unbelief, which he sees as fertile artistic ground. “I’m interested in the grotesque, where you feel attraction and horror at the same time and you can’t reconcile them,” he says. “The place where these opposites collide is powerful territory.”

He’s hardly the first hyperrealist sculptor to provoke a strong reaction. Duane Hanson (1925–1996) generated controversy in the 1960s with his depictions of backroom abortions and motorcycle accidents. Hanson used the technique of life casting—making molds from real people—which lends startling power to his figures. His work influenced Matelli, but while both artists use similar techniques, their aims are different. Hanson set out to shock people, while Matelli says that was not his intention with Sleepwalker.

He’s perplexed by the intense reaction on campus, although he says he understands how the figure could have a triggering effect on certain individuals. Still, it puzzles him that people would find the figure menacing in any way. “For this show, I decided to revisit the idea of a sleepwalker, which I’ve done before, and make him older,” he says. “It’s an opportunity to expand the narrative and declare that this person is still lost after all these years, still sleepwalking.”

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.