Even now I find it hard to believe that I spent 32 years—three-quarters of my adult life—working and living abroad. Can’t possibly be, I mutter, but there it is, the same answer time after time at the end of the equation: 2014 minus 1982 equals 32.

I was 31 when I left Dallas for London in 1982, divorced, childless, eager to know what life might have been like if my forebears hadn’t emigrated from Italy in the early 1900s. I was 63 when I left Paris for Chicago late last August, married, the mother of a serious 17-year-old determined to take her 15 years of ballet training to the next level.

If simple cross-town moves can be tough, those involving international borders are infinitely more fraught. But somehow I, and later we, mastered the art of changing countries and language while living the peripatetic expat life of foreign correspondents: London, Madrid, London, Rome, Warsaw, Berlin, Rome, Paris.

“Lucky you,” people often respond when they ask where we’ve lived. I’m always the first to agree. But I never know how to answer when they follow up with the inevitable, “What’s it like to be home?”

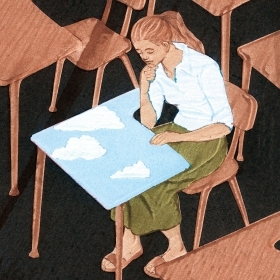

My gut response—a puzzled-sounding “Home?”—tends not to go down well. But the fact is I haven’t felt at home since we moved back, and didn’t expect I would.

Perhaps it’s because I left young, with parents and two grandparents living, and returned a woman of a certain age, the older generations buried. Perhaps it was remarrying and having a child in Italy, then shepherding her through the school system of France before the three of us returned to our passport home, minus a map to navigate.

It’s possible the culprit is the simple passage of time: When I left, Ronald Reagan was president, Britain was about to go to war with Argentina, and UConn was an unheralded basketball backwater. At the time, anyone who thought communism’s grip on Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union was only seven years from utter collapse would have been labeled mad.

Perhaps it’s the sea changes in American life that explain my unease. Who sent our factory jobs to the developing world while I was gone, our secretarial and administrative jobs to customers’ home computers? When did poisonous party politics replace public discourse? Who canonized a new class of oligarchs and decreed that stratospheric wealth was a heavenly nod from the Creator? When did public civility and civic obligation become quaint? How can white police shootings of young black men be back in the news, half a century after Selma—the march, not the movie?

Perhaps it’s the sheer size of this country—big enough to be several nations—that makes me feel unsettled. Whatever the cause, today’s Midwest is a very different country from the New England of my childhood, just as Dallas—where I moved at age 26, four years after graduation from Wellesley—was an altogether different country from my home state of Connecticut.

It may sound odd, but Dallas remains, even today, the most foreign city I ever got to know. Awaiting phone service, I remember stuffing a fistful of quarters into a 7-Eleven payphone to tell my parents I was safely installed. They thought I was kidding about the saddled horse tethered in the warm winter sunshine nearby.

But decades later, my father remembered that call, my voice sounding shaky as I tried to describe how the endless north Texas sky stretched so high and wide that it made me feel dizzy and lost, so totally uprooted, in fact, that moving to London five years later felt almost like moving home.

Our new temporary home of Chicago feels nearly as foreign as Dallas once did: the land too flat, the people too affable and polite, Lake Michigan constantly playing tricks, lulling me—with boat basins and gulls—into thinking I’m finally back to the saltwater life of my childhood.

But the only salt water here comes from the rock salt of winter used on icy roads and sidewalks. No matter how many times my daughter and I walk to the lake’s edge seeking that briny smell of Long Island Sound, we come away without it.

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.