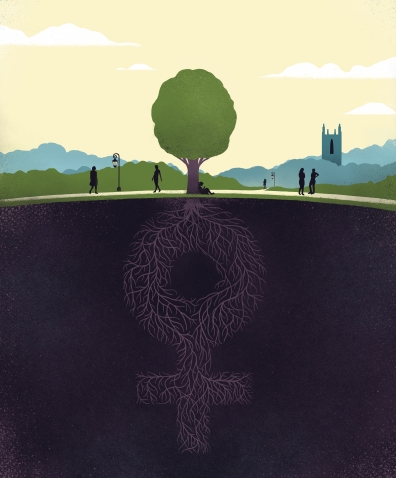

On Wednesday, March 4, the members of the President’s Advisory Committee on Gender and Wellesley gathered in a conference room in the campus center overlooking the snow-covered Alumnae Valley, as they had nearly every week since the group was formed in October. During that time, they had fully immersed themselves in studying the question of what it means to be a women’s college in the 21st century—a time when gender is no longer considered a simple binary of male and female. In particular, the PACGW was asked to focus on what the College’s policies on admission and graduation might be in the future.

But this gathering of the committee was different. It was a meeting that had been called suddenly, earlier in the day, and everyone had a feeling that they were about to hear some big news.

“I had no idea what the policy would be. Literally, no idea. There was nothing I could possibly predict, even after having met the trustees several times,” says Kayla Bercu ’16, a student representative on the PACGW. “I was so nervous. I had to hold one of the other student member’s hands for a couple minutes until I could calm down and pull myself together.”

Then President H. Kim Bottomly came in and sat down. The room fell quiet. She greeted and welcomed the members of the committee, thanked them for their work, and began reading the new policy on gender, which was centered on a reaffirmation of Wellesley’s mission as a college dedicated to the education of women.

“I was just in shock,” says Bercu. “To actually hear that the work we had done helped contribute to this decision was something that I could never have predicted. That feeling was unbelievable. Especially because the decision that was made is one that I personally agree with.”

The next day, President Bottomly and Laura Daignault Gates ’72, chair of the board of trustees, sent out a letter to the Wellesley community announcing the decision. The Wellesley College Board of Trustees had approved the policy recommendations of the Trustee Committee on Gender and Wellesley, which were “informed by the findings of the [PACGW] … ; by inquiry into educational, social, legal, and medical considerations about gender identity; and by extensive conversation and consultation across the community.”

The announcement stressed that the decision was a reconfirmation of Wellesley’s mission to provide an excellent education to women who will make a difference in the world, and stated that the board approved the following admission policy: “Wellesley will consider for admission any applicant who lives as a woman and consistently identifies as a woman.”

A Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) document accompanying the announcement clarified who would and would not be eligible for admission:

- Trans women—those assigned male at birth but who identify as women—are eligible for admission. (See “Gender Terminology.”)

- Individuals who were assigned female at birth who identify as nonbinary and “who feel they belong in our community of women” are eligible for admission.

- Trans men—those assigned female at birth but who identify as men—are not eligible for admission.

The policy calls every student a “valued part of the College culture”—deserving of the full support and mentorship of the faculty, staff, and administration once accepted. If, during a student’s time as an undergraduate, the student no longer identifies as a woman, Wellesley will support the student’s decision to stay at the College or will offer counseling and resources if the student prefers to transfer. From a legal standpoint, Title IX protects the College and allows gender discrimination at the point of admission. Once the student matriculates, however, both federal and state law prioritize the rights of the individual, protecting the student’s right to decide whether to stay or transfer to another institution.

Finally, the policy states that in institutional communications, Wellesley will continue using female pronouns and the language of sisterhood, “both of which powerfully convey important components of our mission and identity,” as Bottomly and Gates said in their letter to alumnae. (See “Sisterhood Is Here to Stay”)

Other women’s colleges have also announced recently that they will open their doors to trans women—Mills, Mount Holyoke, Simmons, and Bryn Mawr—with each school adopting different policies. (While some schools emphasized access for all those who have been discriminated against because of gender or gender identity, Wellesley’s policy reaffirms its focus on women.) Beyond women’s colleges, transgender rights have become a topic of national discussion. Last year, actress Laverne Cox, a trans woman, graced the cover of Time magazine beside the headline, “The Transgender Tipping Point: America’s Next Civil Rights Frontier.” Transparent, an Amazon original series about a trans woman who transitions late in life, won two Golden Globes in January; that same month, the State of the Union address included the word “transgender” for the first time.

The subject may not be unique to Wellesley, but the way the College approached it was distinctly Wellesley, says Adele Wolfson, chair of the PACGW, as well as Schow Professor in the Physical and Natural Sciences and professor of chemistry. “The process was great. It was a very Wellesley thing, that we decided to do it in a thoughtful, academic way. We treated it as both something that was interesting intellectually, as well as pressing politically, and in every other way,” says Wolfson.

Sisterhood Is Here to Stay

When the announcement about the gender decision went out, even before explaining the clarified admission policy, it reassured alumnae that the College will continue to use female pronouns and the language of sisterhood in institutional communications. It was important to include this as part of the decision, says Chair of the Board of Trustees Laura Daignault Gates ’72, because “Wellesley helps women see themselves at the center of the action. And the words that we use, and the way we see ourselves in the examples, and the way we’re addressed, all those things help us do that.”

This means that letters from President Bottomly, language on the College website, and communications with the student body will continue to use female pronouns. However, it will be up to professors to decide what language they want to use in the classroom, and it is expected that individuals’ preferred pronouns will still be respected.

While some students feel that the language of sisterhood erases the existence of members of the trans community at Wellesley, most Wellesley students and alumnae support the decision. “If there is any student who is applying to Wellesley College and doesn’t wholeheartedly believe in being part of a sisterhood, whether they are a sister or not, then I don’t think they should come here,” says Kayla Bercu ’16, a member of the PACGW.

The Conversation Begins

Many alumnae assume that Wellesley began formally discussing this subject in response to the New York Times Sunday Magazine article “When Women Become Men at Wellesley,” which was published on Oct. 19, 2014. In fact, says President Bottomly, the subject was discussed well before then. In the fall of 2013, she and other presidents of women’s colleges began talking about transgender students on campus and what the evolving understanding of gender meant for their institutions. In May 2014, Bottomly and Gates, the chair of the board of trustees, decided that they would bring the subject to the Wellesley community during the 2014–15 academic year. They were taking up the topic, Bottomly said in a video statement to alumnae in December 2014, because recent social change had made it possible for transgender students to express their identities openly and for their peers to accept them when they did so. “That recently acquired freedom that transgender students now feel, as welcome and long awaited as it is, is the answer to why this is a topic now. The broadening societal acceptance of gender fluidity has its flashpoint at single-gender institutes. It’s happening everywhere, but it’s most noticeable here,” Bottomly said.

Soon after the semester started in September 2014, Bottomly announced that she was appointing an advisory committee composed of students, faculty, staff, and alumnae to study the issues raised for Wellesley. By October, the committee was formed—19 members, plus five advisors with expertise in areas of interest to the committee (like student life, for example).

“It was a very big committee and a very diverse committee in terms of previous knowledge,” says PACGW chair Adele Wolfson. “Everybody was interested, obviously, or they wouldn’t have volunteered, but how much people knew, and what their areas of expertise were, and how much personal experience they had, and what their views were, and their ages, and what their academic disciplines were … it was really a very broad committee in a lot of ways.”

Hearing Student Voices

Perhaps the most visible members of the PACGW on campus are its five student members: a first-year, three sophomores, and a junior, with a range of gender identities and a unified commitment to bringing all members of the Wellesley community to a common baseline level of knowledge and understanding about gender. They went through a lengthy process to be nominated for the committee; more than 40 students applied and were interviewed by College Government representatives for the positions.

One of the students who earned a coveted PACGW position was Kayla Bercu ’16, a women’s and gender studies major from New York who identifies as genderqueer. (See “Gender Terminology.”) “That’s because sometimes I wake up and I feel like a boy, and other days I feel like a girl, and some days I don’t decide. Being at Wellesley has given me the opportunity to explore that, and I didn’t even have a word for it before I came here,” says Bercu. (Like some nonbinary individuals, Bercu prefers pronouns differing from the traditional “he” or “she.” Bercu’s personal pronouns are “they/them/their.”) Last year, Bercu worked with the New York City Dyke March “coordinating their new policy to be trans inclusive,” they say. When Bercu heard that there was an opportunity to be part of a committee investigating possible changes to Wellesley’s admission and graduation policies, “I knew I had to be involved, and that was it.”

Bercu has loved “realizing how much people can grow through education.”

‘This deepening of our understanding of women, and what it means to be a woman in the 21st century, and the importance of women’s colleges in the 21st century, all it does is make [Wellesley] stronger, and make me, and I think a lot of other people, more committed to our mission.’

—Laura Daignault Gates ’72, chair of the Wellesley College Board of Trustees

“We had one student who came to our Gender 101 workshop, and she said, ‘I have never even heard of this stuff before. Thanks so much for holding this workshop.’ And she came back for the dinner and the trustees’ discussion [in February] because she had that background, and she had solidified opinions. She was ready to advocate, and be like, ‘Trans women are women. I know what this means,’” Bercu says. No matter what their position is, education on gender identity makes people “better situated to express [their views] in a way that everyone can understand, and that isn’t offensive or emotionally charged.”

The first-year student on the PACGW, Sofie Werthan ’18, joined the committee just weeks after first arriving on campus. Although she led organizations that deal with gender and sexuality through her high school and the San Francisco Jewish Community Center, she was excited to be part of a community where there are many more people who are open about their identities. “A great experience for me personally is really understanding that these aren’t theoretical concepts. They are also people’s lived experiences, they’re people’s identities, and whatever you do is going to have a very real impact on current students and potential students,” Werthan says.

The Times Article

Naturally, the PACGW students thoroughly discussed the New York Times article with the rest of the committee.

“I think the tone of the article was probably the most damaging, that it represented trans men on campus as being an enormous group that was threatening and was going to take over the spirit of the College,” says Wolfson. According to the results of a PACGW campus survey, trans men only represent about 0.3 percent of the student population, which is comparable to estimates of transgender individuals in the U.S. population overall. (By contrast, the number of male students taking classes on campus from Olin, Babson, or MIT is about 2 percent any given semester.) In addition, the survey found that 4 to 5 percent of Wellesley students consider themselves nonbinary.

Also, Bercu says, “the article misgendered many of the students that they interviewed. It was really quite awful. Many of the people who were interviewed don’t identify as male. In fact, they identify as nonbinary and have no plans on medically transitioning to another gender.” Also, many students objected to the fact that the article focused on trans men, and did not address the fact that many students had been trying passionately to get the College to accept applications from trans women for some time.

The Learning Curve

While the student members of the PACGW showed up at the first committee meeting already very conversant with issues around gender identity, many others on the committee had a lot to learn. Lia Gelin Poorvu ’56, a former Wellesley trustee, says that when she first joined, she knew very little about the subject.

“I taught French literature for 40 years, so I certainly thought I knew a lot about the human experience. And yet, I must say, until recently, I didn’t know the difference between gender and sexuality. So you see, it’s definitely a generational thing. Even if I thought I was keeping up and I was reading, I really was quite behind the times. So it was a tremendous learning process,” she says.

Poorvu gives the students on the PACGW a lot of credit for helping her along. For example, a small Gender 101 handbook the students made explains that “gender is a person’s internal concept of who they are and how they identify,” sexual orientation is who a person is attracted to, gender expression is how they present themselves, and “sex is a person’s external physical appearance, specifically their reproductive organs and hormones.” Like the rest of the committee, Poorvu also did extensive reading. “You should see what my house looks like with these piles of books and papers,” she says. And through all this work, “I’ve come to the realization that our understanding of gender identity has evolved. Gender evolves, and my views have evolved, and probably the more we know, the more they will continue to evolve. I am delighted that Wellesley has dealt with these issues openly and is maintaining its identity as a women’s college with this broader definition of women.”

The Campus Conversation

One of the most successful events of the year, say members of the PACGW, was a dinner where students could meet and share their thoughts with members of the Trustee Committee on Gender and Wellesley. On Feb. 3, over 150 students braved snowdrifts to go to Tishman Commons in the campus center and talk gender and Wellesley over pasta and salad. Attendees were randomly placed at small tables, to make sure that most tables had a mix of students, PACGW members, and trustees. “It was wonderful,” says Poorvu. “I just listened and learned so much. … I was impressed with how articulate [the students] were, and very, very respectful of other people’s opinion.”

Ellen Goldberg Luger ’83, the chair of the trustee committee, had a similar experience. “The students on the PACGW did a fantastic job of setting the context for the discussion. … We talked a lot about the mission of Wellesley, and what that means to each of us, and how we viewed this process and this decision in the context of educating women,” Goldberg Luger says. “I think the format of the dinner allowed everyone to feel that they could express how they genuinely felt. They could ask questions. It was just a very candid and open and honest dialogue.”

‘For me, the most important thing is that we reaffirmed the mission of Wellesley College, to educate women, and it is as important today as it was when the College was founded.’

—Ellen Goldberg Luger ’83, chair of the Trustee Committee on Gender and Wellesley

Evan Segreto ’15, a genderqueer student whose preferred pronouns are “they/them/their,” was a facilitator at the dinner with the trustees. “I didn’t expect it to be good, but … the trustee at my table was very, very respectful. She was trying very hard to educate herself. … She came very open-minded and very willing to engage, and I thought it was great,” they say. “That gave me a lot of hope.”

Unfortunately, the dialogue on campus around gender identity hasn’t always been as open, says Segreto, who is copresident of both Siblings, Wellesley’s transgender/genderqueer group, and Tea Talks, the Asian/Pacific Islander queer group. “I think that the opinions within the trans community are probably as diverse as the opinions in the general community. But my pocket of friends in the trans community, we have felt a little bit afraid to voice our opinions,” Segreto says. “It’s been uncomfortable hearing things. … I kind of walk around thinking, well, are these the people who think that I don’t belong here?”

Many students—of all points of view—have raised the question of whether Wellesley is a “safe space” for discussing issues around gender. This concern was voiced anonymously by many students through the PACGW survey. “I think that the climate to discuss gender at Wellesley is uncomfortable and overwhelmingly liberal—to the point where the presumed minority (although it may be majority) is afraid to voice their opinion that they want Wellesley to be a women’s college,” one student wrote. Another commented, “Those who have tried to speak out in disfavor of these issues in the past, particularly on Facebook, have been met with anger, disdain, and disrespect, therefore discouraging others from opening up.”

Hana Glasser ’15, the 2014–15 College Government president, thinks that one thing that might help create a climate where people feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns, whatever they may be, is offering more opportunities like the trustee dinner. “It’s a very Wellesley fear of being wrong, or saying the wrong thing, or doing the wrong thing, because we aren’t used to saying or doing the wrong thing,” she says. “I think creating these more natural settings, where people can bounce ideas off each other, where people can explain who they are and where they’re coming from, [is] so much more constructive when it comes to something this delicate than these big forums. … That’s a model that we should use for more things on campus.”

‘The process was great. It was a very Wellesley thing, that we decided to do it in a thoughtful, academic way. We treated it as both something that was interesting intellectually, as well as pressing politically, and in every other way.’

—Professor Adele Wolfson, chair of the PACGW

A Decision Is Made

As the PACGW was doing its work on campus, the members of the parallel committee of trustees were also at work educating themselves and preparing a recommendation to put before the board of trustees.

One of the members of the trustee committee was Judy Ann Rollins Bigby ’73, a physician and former Massachusetts secretary of health and human services who is now a senior fellow at Mathematica Policy Research. “I’ve had the experience that with these sort of committees, there’s a preconceived idea of what the outcome is going to be, and the committee doesn’t really have a chance for much input. But that was definitely not the case here,” Bigby says. “It was really clear that people were learning as we went through this process, and it was really nice to see that people were open to the discussion and perhaps to thinking about something in a different way.”

For Laura Gates, the chair of the board of trustees, “This deepening of our understanding of women, and what it means to be a woman in the 21st century, and the importance of women’s colleges in the 21st century, all it does is make [Wellesley] stronger, and make me, and I think a lot of other people, more committed to our mission.” Goldberg Luger, chair of the trustee committee, agrees. “For me, the most important thing is that we reaffirmed the mission of Wellesley College, to educate women, and that it is as important today as it was when the College was founded.”

The Response

The reaction to the decision has been overall positive, from both students and alumnae. Wellesley College Alumnae Association Executive Director Missy Siner Shea ’89 says that a majority of the emails in response to Bottomly and Gates’ announcement—which came from the classes from the 1940s to the most recent grads—were supportive. “I believe you have arrived at a caring and clear policy which I support. Women’s colleges still have an invaluable role to play in our society,” wrote one alumna from the 1950s. Another woman from the 1970s commented, “I am forever grateful for my own experience and education at Wellesley, where women were and remain central, and am profoundly proud that the College remains committed to providing this experience to future generations of women.”

Shea says that most of the responses that were not positive were requests for clarification about what happens when a student no longer identifies as a woman after matriculation. Very few alumnae expressed concern about trans women now being eligible for admission.

Some students have criticized the policy as inconsistent and unfair since it excludes nonbinary individuals who were assigned male at birth while accepting those assigned female at birth. In response to that concern, Gates comments, “If you think about our mission as a women’s college, in our view, having people who are assigned male at birth who are nonbinary is not in keeping with the mission.” And there are students who agree with the decision, saying that it is a way to ensure that applicants have lived experience as women.

Moving Forward

Now that the gender policy has been approved, many departments across campus are working to implement it, from residential life to health services. The first class to enter under this new policy will be the class of 2020, who are currently completing their junior years in high school. A working group comprised of several members of the Board of Admission and the committee that oversees financial-aid policy will recommend an implementation plan that includes a set of best practices and guidelines in advance of the 2015–16 admission cycle. This work is expected to be completed in the coming months. The PACGW will also continue to work together.

College Government President Glasser says that a lot of the conversation now on campus among students is about implementation. First, how are students going to be involved in the process going forward, and second, how are trans women going to be involved in the conversation? “The mandate now is to make Wellesley as welcoming and accepting a place as possible for new students,” she says.

‘To actually hear that the work we had done helped contribute to this decision was something that I could never have predicted. That feeling was unbelievable. Especially because the decision that was made is one that I personally agree with.’

—Kayla Bercu ’16, PACGW member

PACGW first-year Werthan says it is crucial to continue the education that happened on campus this year. “It’s not a one-time workshop where you learn terminology. … Everyone is so socialized, especially regarding gender, from such a young age, that it’s so simple: There are men and women. It’s seen as natural and innate. And transgender people don’t conform to those simple notions, so you have to undo so much socialization to really understand the complexity of gender and really get to the heart of the matter.”

But Werthan believes that Wellesley is up to the challenge. “Wellesley is not facing this existential crisis that the New York Times would lead you to believe. And definitely, I think Wellesley is still a place for empowerment and education and learning, and we’re not falling to the ground and losing all the things that make alums love it so much,” she says. She thinks that her great-grandmother Leah Rose Bernstein Werthan ’29 and her great-great-aunt Edith Bernstein Frankel ’28 would still recognize their alma mater. “Our traditions are still going strong. I mean, things are changing. That’s just what happens. Things evolve. But at its core, Wellesley is still the institution that has made such great leaders out of so many women.”

Sex The classification of people as male or female. Sex is usually assigned at birth based on external anatomy but is determined by characteristics like chromosomes, hormones, and reproductive organs.

Gender Identity One’s internal, deeply held sense of one’s gender. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not visible to others.

Gender Expression External manifestations of gender, expressed through one’s name, pronouns, clothing, haircut, behavior, voice, or body characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine and feminine, although what is considered masculine and feminine changes over time and varies by culture. Typically, transgender people seek to make their gender expression align with their gender identity, rather than the sex they were assigned at birth.

Cisgender A term used by some to describe people who are not transgender. “Cis-” is a Latin prefix meaning “on the same side as.”

Genderqueer A term used by some people who experience their gender identity and/or gender expression as falling outside the categories of man and woman. They may define their gender as falling somewhere in between man and woman, or they may define it as wholly different from these terms. The term is not a synonym for transgender.

Nonbinary Similar to genderqueer, this is a way of describing people who do not identify as men or women and instead exist between or outside the gender binary that society upholds.

Transgender A term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from what is typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. Many transgender people are prescribed hormones by their doctors to change their bodies. Some undergo surgery as well. But not all transgender people can or will take those steps, and a transgender identity is not dependent upon medical procedures.

Trans men People who were assigned female at birth but identify and live as men may use this term to describe themselves. Some may prefer to simply be called men, without any modifier.

Trans women People who were assigned male at birth but identify and live as women may use this term to describe themselves. Some may prefer to simply be called women, without any modifier.

Source: GLAAD

Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’99 is a senior associate editor at Wellesley magazine.

Lisa Scanlon Mogolov ’99 is a senior associate editor at Wellesley magazine.

There are many resources for further education on the website of the President’s Advisory Committee on Gender at Wellesley. Go to the MyWellesley portal on www.wellesley.edu to access the site. You will be prompted to use your Wellesley Login. (For instructions on setting up your login, visit www.wellesley.edu/alumnae/wellesleylogin. Or contact the Wellesley Computing Help Desk at helpdesk@wellesley.edu or 781-283-3333.)

We ask that those who engage in Wellesley magazine's online community act with honesty, integrity, and respect. (Remember the honor code, alums?) We reserve the right to remove comments by impersonators or comments that are not civil and relevant to the subject at hand. By posting here, you are permitting Wellesley magazine to edit and republish your comment in all media. Please remember that all posts are public.